After the seismic convulsion of grief that greeted Byron’s death, these quieter after-shocks recorded in the Hucknall Album might come as no surprise, but they still raise teasing questions about his place in English cultural life. Among those hundreds of visitors many might have been hard pressed to say what had brought them, and yet in a curious sense it is the presence of the ‘common man’ – the great battle cry of Diana’s funeral – rather than of Washington Irving or the Duke of Sussex that is the most intriguing aspect of the Byron cult.

For a man of Sussex’s liberal pretensions, the pilgrimage carried clear and deliberate political overtones, but precisely what kind of ‘fane’ did those hundreds of obscure admirers imagine they were visiting at Hucknall? What were parents doing, signing the visitors’ book with their daughters, paying homage at the shrine of a man who had publicly ridiculed every tie of family life? Why were army or naval officers at the tomb of a poet who took such pride in sharing Napoleon Bonaparte’s initials? What did good protestant Englishmen think they were up to, leaving messages that would not look out of place at the foot of the Bambino in Rome’s Aracoeli? What was it that brought so many clergymen to the grave of a writer the Bishop of Calcutta had labelled the ‘systematic poet of seduction, adultery and incest; the contemner of patriotism, the insulter of piety, the raker into every sink of vice and wretchedness to disgust and degrade and harden the hearts of his fellow-creatures’? 11 What was nineteenth century England doing longing after ‘a perfected idol … as the Israelites longed for the calf in Horeb’? 12

The most exciting answer to these questions is that Byron had come to represent a subversive element in the national character for which the encroaching morality of the nineteenth century allowed less and less expression. In his wonderfully contrary study of the Byrons, A.L. Rowse once went so far as to claim that Byron was scarcely English at all, and if this is a characteristic overstatement, Rowse is right that the values Byron embodied have always prospered on the margins of English life rather than at its centre, a source of equal fascination and fear to a country reluctant to recognise its own complex identity.

‘Into what dangers would you lead me, Cassius’, a nervous Brutus asks in Julius Caesar,

That you would have me seek into myself

For that which is not in me?’

and the fear that accompanied Byron to the grave was the fear of what he had shown them in themselves. * ‘Every high thought that was ever kindled in our breast by the muse of Byron’, Blackwood’s protested, expressing the sense of outrage and almost self-disgust that his readers came to feel as the full implications of their ‘idolatry’ were brought home to them,

every pure and lofty feeling … is up in arms against him. We look back with a mixture of wrath and scorn to the delight with which we suffered ourselves to be filled. 13

It is this that gives the history – and the posthumous history – of Byron its continuing importance because he raised demons that no community could afford to acknowledge or allow to live. In a wonderful sequence near the beginning of Stanley Donen’s Charade George Kennedy opens the west door of a church, strides down the aisle to where an open coffin rests between banks of candles on its bier, stares for a moment at the body, takes a pin out of his raincoat lapel, jabs it into the corpse to make sure it is dead, turns on his heel and strides out again.

There was something of that about Byron’s funeral – the mood along the Tottenham Road seemed to George Borrow like that of an execution – because for all its beauty and fascination the tiger was safer dead. There was nothing feigned in the grief and loss of the young Tennyson or Carlyle, and yet from the notorious day that his closest friends burned his memoirs in John Murray’s offices to the letters George Eliot sent Harriet Beecher Stowe, even Byron’s most passionate admirers needed to deny or suppress the truths that his life embodied. John Cam Hobhouse, that loyal ‘bulldog’, told Tom Moore in a conversation about the memoirs, that he knew more of Byron than anyone else, and much more than he should wish anyone else to know.

‘Yet each man kills the thing he loves’ 14 wrote a later exile from these shores, and along with the adulation, Byron has always inspired an anxiety that ranges from comic wariness to suspicion, fear and open hatred. Through the novels of the nineteenth century Byronic imitators would continue to stalk the Caucasus or the moors with all the misanthropic glamour of their original, but from Persuasion to Jane Eyre, from Glenarvon to Dracula, from Mary Shelley’s Raymond to Polidori’s Ruthven – the first vampire in English fiction – ‘Byronism’ is a physical threat to be feared, shunned, exiled, immolated, staked through the heart or – that most English of solutions, – blinded, crippled and then, ‘Dear Reader’, married.

It is only too appropriate that Mary Shelley’s name should feature on this list, because no one has so painfully united what D. H. Lawrence called the ‘ predilection d’artiste ’ 15 for the aristocrat with a bourgeois fear of everything he stands for. ‘For there does exist, after all,’ Lawrence wrote in his great essay on Thomas Hardy – an essay characteristically less about Hardy than Lawrence himself –

… the great self-preservation scheme, and in it we must all live … But there is the greater idea of self-preservation, which is formulated in the state, in the whole modelling of the community … In the long run, the State, the Community, the established form of life remained, remained intact and impregnable, the individual, trying to break forth from it, died of fear, or of exhaustion, or of exposure to attacks from all sides, like men who have left the walled city to live outside in the precarious open. This is the tragedy of Hardy, always the same: the tragedy of those who, more or less pioneers, have died in the wilderness, whither they have escaped for free action, after having left the walled security, and the comparative imprisonment, of the established convention. This is the theme of novel after novel: remain quiet within the convention, and you are good, safe and happy in the long run, though you never have the vivid pang of sympathy on your side; or, on the other hand, be passionate, individual, wilful, you will find the security of the convention a walled prison, you will escape, and you will die, either of your own lack of strength to bear the isolation and the exposure, or from direct revenge from the community, or from both. This is the tragedy, and only this. 16

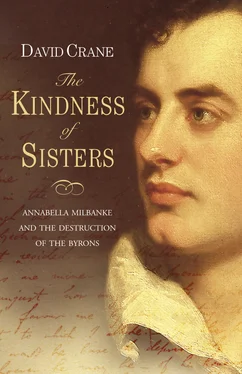

This book is the story of that tragedy, because supreme among the Lawrentian outsiders is Byron, an aristocrat in the conventional sense by a convoluted accident of inheritance, an aristocrat in the Lawrentian sense to the core. It has been plausibly argued that Byron was never in fact at ease with the chance that brought an impoverished Aberdeen schoolboy a title, but from that day in 1812 when, as the author of Childe Harold, he ‘woke to find himself famous’ his life became a paradigm of Lawrence’s struggle between the individual and the community – the archetype of all those artists forced into exile, compromise or silence by the hostility of the crowd, of the men and women who have had to pay with their freedom or security for their integrity, the living victims of that same communal, English instinct for self-preservation that pushed Hardy to sacrifice his heroes and heroines on the altar of social convention.

Crippled with a deformity of his right foot, abandoned by his rake of a father, brought up in poverty by his violently possessive mother, alternately abused and terrified by his Calvinist nurse, Byron might have had little choice in the matter, but no psychological pleading can disguise the gusto with which he embraced his fate. In recent years it has become the fashion among biographers to present him as some kind of ‘monster-victim’ of this childhood, but the exhilarating truth about Byron is that he was an outsider by intelligence and will, an enemy by instinct, sensibility, temperament and politics of all that this ‘tight little island’ * stands for.

Читать дальше