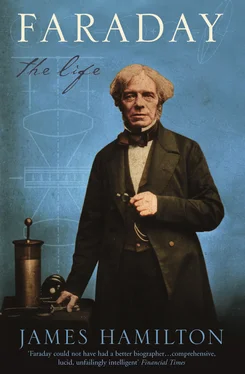

If the day had been clear, he might have been rewarded by an incomparable view of Paris. There in the middle distance, then beyond woods and ramparts, lay the city – a small carpet of white, cream, grey, and threads of dark red. The towers of Nôtre Dame stood out crisply, then as now, beside the florid Tour St Jacques, and the roofs of the Louvre draw a line which divides Paris in two along the river. The Seine, low-lying and kept in its place by embankments, is and was then barely visible from Montmartre. Floating upon the city like tethered hot-air balloons are the gleaming domes of the Institut, Les Invalides and the Pantheon, the only building to break the skyline at Montparnasse. But Faraday noted nothing about the view; what instead caught his eye was the clunking telegraph mounted on a tower nearby, which passed its unending semaphore messages to Paris from Boulogne and Lille. By means of the telegraph, Napoleon’s officials could communicate with each other rapidly. According to Andrew Robertson, who also saw the telegraph at work, it took six minutes for a message to reach Lille from Paris, and for an answer to be received. 15Faraday describes the telegraph relay, and adds a little drawing for good measure. He points out that ‘They are very different to the English telegraphs, being more perfect and simple.’ 16

There, standing on a Paris hillside, was a young citizen of an enemy country, who had already aroused the curiosity of the plaster-burners, sketching the equipment that kept Napoleon’s intelligence flowing around the country. How extraordinary that he was not arrested as a spy.

Wandering in these last few days more widely about Paris, Faraday watched a man touting for custom at a ‘Try your Strength’ machine on the Pont des Arts. He also tumbled to the answer to a problem that had been pestering him for some time – what was the occupation of ‘certain men who carry on their backs something like a high tower finely ornamented and painted and surmounted in general with a flag or vane’, which had a flexible pipe attached to it? The answer was that ‘these men are marchands des everything that is fit to drink’, 17water- or lemonade-carriers.

Sir Humphry had not yet made it clear to the party when they were to leave Paris. It had been on and off for days, but there must have been some indication that departure was imminent because on 18 December Faraday went to the Prefecture of Police to get a passport for interior travel in France, and on Christmas Eve he was writing: ‘we expect shortly to leave this city, and we have no great reason to regret it. It may perhaps be owing partly to the season and partly to ignorance of the language that I have enjoyed the place so little. The weather has been very bad, very cold, much snow, rain &c have continually kept the streets in a foul plight.’ 18

But there was one final fine Parisian extravaganza before they departed: Napoleon and the Empress Marie-Louise were to visit the Senate in full state on 19 December. The weather was cold and wet, but Faraday stuck it out on the terrace of the Tuileries, and eventually the long procession of trumpeters, guards and officers of the court wound into sight. At the end of the procession Faraday caught a glimpse of Napoleon in an opulent carriage surmounted by fourteen footmen, ‘sitting in one corner of his carriage covered and almost hidden from sight by an immense robe of ermine, and his face overshadowed by a tremendous plume of feathers that descended from a velvet hat. The distance was too great to distinguish the features well, but he seemed of a dark countenance and somewhat corpulent’ The Emperor was received by his citizens in complete silence: ‘no acclamations were heard where I stood and no comments’. 19

There were, however, joyful acclamations from some members of Sir Humphry Davy’s party in the morning of 29 December, for, as Faraday writes, ‘this morning we left Paris’. 20

CHAPTER 6 A Point of Light

They were all elated. It was freezing cold, bad enough for Sir Humphry and Lady Davy sitting inside the carriage, but deadly for those outside in the air. They were heading for Nemours, forty miles south of Paris, to spend the night, but it was evening before they reached the Forest of Fontainebleau. There had been no heat in the sun all day, and by evening the trees were still covered in hoar frost. This moved Faraday to lilting, Coleridgean prose.

… we did not regret the severity of the weather, for I do not think I ever saw a more beautiful scene than that presented to us on the road. A thick mist which had fallen during the night and which had scarcely cleared away had by being frozen dressed every visible object in a garment of wonderful airiness & delicacy. Every small twig and every blade of herbage was encrusted by a splendid coat of hoar frost, the crystals of which in most cases extended above half an inch. This circumstance … produced an endless variety of shapes and forms. Openings in the foreground placed far-removed objects in view which in their airiness, and softened by distance, appeared as clouds fixed by the hands of an enchanter: then rocks, hills, valleys, streams and roads, then a milestone, a cottage or human beings came into the moving landscape and rendered it ever new and delightful. 1

Sir Humphry was also moved to such pictorial levels of passionate exclamation as they galloped through the forest. The experience drew the romantic poet out of him, forty lines of passion. This is a sample:

The trees display no green, no forms of life;

And yet a magic foliage clothes them round,-

The purest crystals of pellucid ice,

All purple in the sunset … 2

This poem captures an essential difference in outlook between Faraday and Davy. In worldly affairs Faraday was naïve, ignorant, and wilfully avoided considering political issues. His understanding of the very dangerous situation in France was practically non-existent. Blundering about a Parisian quarry, patently the uninformed Englishman, openly sketching Napoleon’s telegraph equipment, he was being careless in the extreme. He felt an unfortunate, but at the time perfectly commonplace, kind of juvenile superiority over the French and the Italians, and this emerges regularly in his account of the continental journey.

Davy, however, though feeling superior to most people around him, had political antennae. He saw the importance of racing to an understanding of what iodine was before Gay-Lussac got to it; knowledge was power. He saw, too, the importance of putting on a theatrical show of chemical effects for the French scientists, and making them nervous. And he saw the importance of not appearing impressed by the treasures in the Louvre. So, at the end of his versification, Davy gives the lines a twist, and turns them into poetry. He draws a picture of a golden eagle on the gorge at Fontainebleau:

… the bird of prey, –

Emblem of rapine and lawless power:

Such is the fitful change of human things:

An empire rises, like a cloud in heaven,

Red in the morning sun …

… soon its tints

Are darken’d, and it brings the thunder-storm, –

Lightning and hail, and desolation comes;

But in destroying it dissolves, and falls

Never to rise!

Davy could handle allegory; indeed his whole imaginative life was wreathed in it, his visionary writings were driven by it, and his later writings suggest that towards the end of his life he was taken over by it. Faraday, on the other hand, saw the natural world as part of the revealed truth, the real thing, and his life’s work came to be dedicated to understanding the purposes behind nature – God’s purposes, in his view – and to explaining them in their most direct terms to humanity.

Riding through the Forest of Fontainebleau as the winter’s day, and the year 1813, drew to their close, Davy and Faraday were separated by more than the roof of the carriage. Davy was inside, looking out of the window to the right or left. Faraday, however, sitting up with the driver and the luggage, could see from an aerial perspective the entire 360 degrees around him, and the zenith of the skies. The man of allegory was enclosed from the world; the budding scientist of revealed truth was out within the elements.

Читать дальше