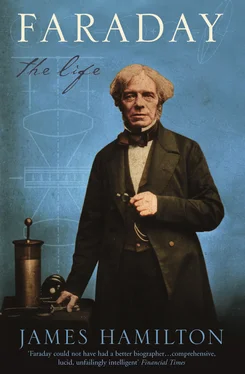

Humphry Davy and Michael Faraday are connected for all time as teacher and pupil, master and assistant, milord and valet, tyrant and subject. From a perspective of two hundred years, however, they stand at equal but separate stature. Michael Faraday’s upbringing, with its twin constraints of impending poverty and strict religion, had a third ingredient of tight urban boundaries. Unlike Davy, who roamed the Cornish moors as a youth and declaimed poetry into the winds, Faraday did not see a moor, or any wild space, or much green, until he travelled abroad with his master. Davy wrote poetry, and had friends among poets, and his interconnected lifelong series of personal quests for discovery began through his poetic writing as he divined the nature of the earth and his place in it. The core of his achievement is in the isolating, naming and proving of unique entities – nitrous oxide, chlorine, potassium, iodine, the Davy Lamp – each a link in a chain. By the time he died in 1829 he was separated from the culture to which he had contributed so much by illness, distance and attitude. His final years, spent apart from his wife and wandering in Europe, found him speaking largely to himself in a series of visionary writings about travel, the rise and fall of civilisations, interplanetary voyaging and fishing. Davy was a man of the early Romantic movement – prodigious, interrogative, eye-catching and original are words that illuminate him.

In the late summer of 1813 Sir Humphry and Lady Davy laid plans for a tour, lasting perhaps two or three years, to France, Switzerland, Germany, Italy, and thence into Greece and Turkey. The first object was to enable Davy to collect the medal awarded him by the Emperor Napoleon and the Institut de France for his electrochemistry. This itself had been the cause of controversy, of accusations of treating with the enemy. Davy wrote to Thomas Poole:

Some people say I ought not accept this prize; and there have been foolish paragraphs in the papers to that effect; but if two countries or governments are at war, the men of science are not. That would indeed be a civil war of the worst description: we should rather, through the instrumentality of men of science, soften the asperities of national hostility. 64

Along the route Davy planned to meet, talk and experiment with the continental scientists with whom he had corresponded. Though Britain was at war with France, Davy, a scientist renowned in France and now honoured by Napoleon, obtained a passport for himself and his party. This comprised his wife, her lady’s maid, his Flemish valet La Fontaine, a footman, and Michael Faraday as Davy’s assistant. Sir Humphry had not had personal staff before, this was an introduction of Jane’s: a man in his position must have a valet. A few days before departure, however, the valet’s wife refused to let her husband go to Boney’s France for so long, and Faraday was asked to do his job, with the promise that Davy would hire a replacement in Paris. Attending to Sir Humphry’s personal needs was not quite what Faraday had bargained for, but he could hardly refuse and risk being left behind.

‘I’ll see you tomorrow about 1 o’clock,’ Faraday wrote briefly to Benjamin Abbott early in October, perhaps to give him the news, 65and on 13 October 1813 the party of five set off.

CHAPTER 4 ‘The Glorious Opportunity’

At eleven o’clock on that crisp autumn morning the coach rolled off from the Davys’ house in Grosvenor Street. Sir Humphry and Lady Davy and the lady’s maid travelled inside the shining black carriage; Michael Faraday and the footman were outside, on the roof, with the driver. Those three had to stand all the force of the weather, but they also got the fresh air and the view, and for Faraday this was central to his enjoyment of the journey and his record of it.

In one of the fullest and most exciting travel documents of the period, Faraday wrote a long account of his tour with the Davys. 1The peculiarity of the Journal is not only its detail or its length – nearly four hundred pages of Faraday’s fluent hand, whippy, spiky letterforms, sloping elegantly to the right – but its purpose and arrangement. The volume contains descriptions of two extended tours made by Faraday, the first to Europe from October 1813 until April 1815, the second to south Wales in 1819. The accounts blend into one another: on page 46 the continental diary breaks off in mid-sentence and, after a blank sheet or two, dives straight into 150 pages on the Welsh trip. Then the continental journey takes over again, with a description of the Parisian water supply, and leads us for a six-month dance through France, over the Alps, down to Genoa, Turin, Florence, Siena and Rome, where it cuts off again in mid-sentence, this time finally. A diary of the subsequent months of the journey, to Naples, back to Rome, into Switzerland and Germany, and back to Italy again before returning home is now lost, but long extracts were published in Henry Bence Jones’s biography of Faraday in 1870. 2

The document that we have must be a second version, written up from initial notes, at home in some of the long evenings before Faraday married in 1821. 3A pencil note inside the front cover gives his reasons for writing the diary:

This journal is not intended to mislead or to inform or to convey even an imperfect idea of what it speaks. The sole use is to recall to my mind at some future time the things I see now and the most effectual way to that will be I conceive to write down be they good or bad or however imperfect my present impressions.

The keeping of the diary was thus Faraday’s attempt to grapple with the chronic memory loss which dogged him from his youth in bouts and flashes, an inability to recall anything from common events to complex thoughts, and which would lead him to deep melancholia and threaten at times to destroy his career. This also drove his compulsion, encouraged by Isaac Watts’s advice, to take detailed notes, and to write them up – from John Tatum’s and Humphry Davy’s lectures, and from his own laboratory experiments. The deliberate and full process of laboratory notes that Faraday practised and introduced as a standard for all scientists thereafter derived not so much from a desire to record, as from his deep-seated and desperate fear of forgetting.

Everything Faraday writes of the days on the move comes from the elevated perspective of the top of the carriage, is bathed in the light of day, and swings with the rhythm of the coach. He was apprehensive when they set off – quite naturally, for as he wrote in his opening paragraphs, he had never before ‘within my recollection’ been further than twelve miles from London. ‘But curiosity has frequently incurred dangers as great as these and therefore why should I wonder at it in the present instance.’ 4‘This morning formed a new epoch in my life,’ he mused, as he awaited the fresh curving landscapes and the insights to come.

The party trotted off along Park Lane to Hyde Park Corner, through Kensington and west towards Hammersmith and Kew. Their destination that evening was Amesbury, north of Salisbury, eighty-five miles away along what is now the A30. At the comfortable pace of ten miles per hour, with a change of horses at Basingstoke, they should have made it before nightfall. The next morning was cooler, probably cloudy. They skirted the edge of Salisbury Plain, seeing Stonehenge across the fields, but made all speed for Exeter, where they ‘arrived rather late and put up for the night’, Faraday wrote. ‘I have before me at this time the Cathedral but it is too dark to see it distinctly.’ 5

If the first two days’ journey was a novelty for Faraday, the third was a revelation: ‘Reached Plymouth this afternoon. I was more taken by the scenery today than by anything else I have ever seen. It came upon me unexpectedly and caused a kind of revolution in my ideas respecting the nature of the earth’s surface.’ 6

Читать дальше