All through your book I was wondering if it would have been easier to die or take the shit you did. But now, when I think of your book, I say if you were dead then you would not have been able to give what you did through your book. To imagine me not being able to write you this letter or thinking that they could beat you into giving up, man, that would be too much. We need more like you to set examples of what courage is all about!

Hey, Brother, I’m going to let it go. Please write back. It will mean a lot.

Your friend,

Lesra Martin

Lesra’s words, his efforts to reach out, touched Carter. He responded on October 7. The one-page typewritten note thanked Lesra for his “outpouring of hope, concern and humanness … The heartfelt messages literally jumped off the pages.”

More letters followed between Lesra, his Canadian guardians—who had essentially adopted the youth to educate him—and Carter in which they discussed politics, philosophy, Carter’s own case, and his appeal. But when Lesra asked if he could visit the prison at Christmastime—he was going to be in Brooklyn seeing his family—Carter replied noncommittally. That did not deter Lesra. The bond between the two—and, more important, between Carter and this mysterious Canadian commune that typically shunned friendships with the outside world—had been sealed.

Winter’s chill could be felt inside the Trenton State Prison on that last Sunday of December. Built in 1836 by the famed British architect John Haviland, the prison is a brooding, monolithic fortress. Haviland used trapezoidal shapes and austere giganticism to evoke a massive Egyptian temple. Scarab beetles, which symbolized the soul in ancient Egypt, were carved into the prison’s pink limestone walls. Tributaries from the Delaware River flowed in front of the prison, in faint mimicry of the Nile.

But by 1980 the waterways had long since dried up and the pink limestone had turned brown. Loops of razor-ribbon wire topped twenty-foot-high concrete walls, and stone-faced guards stood in gun towers. The prison yard, with a softball field, weight machines, and handball courts, was said to sit over a cemetery. The yard’s red dirt was so dry that it was regularly sprayed with oil, creating a viscous sheen that rubbed off on inmates in crimson splotches.

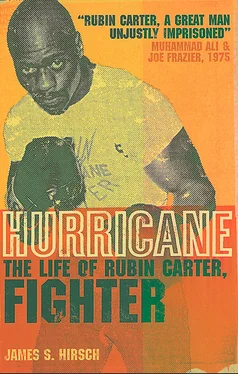

While the prison sought total control of its inmates, Carter defied the institution at every turn. He did not wear its clothes, eat in its mess hall, work its jobs, or participate in any organized activity. He refused to meet with prison psychiatrists, attend parole hearings, or carry his prison identification card. His rationale was simple: he was an innocent man; therefore, he would not be treated like a criminal. His defiance earned him several trips to a subterranean vault known as “the hole,” where inmates were held in solitary confinement. He was also once banished to a state psychiatric hospital, where the criminally insane and other incorrigibles were disciplined.

But Carter had a predatory instinct for survival, and he was eventually allowed to live quietly in his fourth-tier cell. He continued to fight for his freedom in the courts, but by now he had immersed himself in books on philosophy, history, metaphysics, and religion. Searching for meaning in his own life, he turned his cell into “an unnatural laboratory of the human spirit.” He studied, wrote, and tutored other inmates about the need to look within themselves to find answers to the world outside.

Carter had been on this personal journey for more than two years by the time a guard came to his cell and told him he had a contact visitor. Suspecting it was the letter-writing youth, Carter walked down his tier, through the center hub of the prison, and past the infirmary, which was conveniently next to the Death House. (The infirmary used to receive the electrocuted bodies.) Before entering the Death House, he gritted his teeth and disrobed for a strip search—standard procedure for every prisoner before and after a contact visit. Searching for contraband, a guard ran his hand through Carter’s hair and looked inside his mouth, under his arms, beneath his feet, and up his rectum. This degrading invasion was another reason Carter avoided contact visits.

Once inside the chamber, Carter reserved a cell on the lower tier, placing his plastic identification tag and a pack of Pall Malls on two chairs. The prison visitors soon filed in and quickly joined their friend or loved one. Finally, only two people were left—Carter and a slip of a youth. The young man was trembling.

Growing up in the slums of Brooklyn, Lesra Martin knew plenty of people who had gone to prison, but this was his first time inside a pen. The high stone walls, metal gates, and claustrophobic corridors were imposing enough, but the brusque security checks were even more unnerving. He emptied his pockets, was frisked, was scanned by a hand-held metal detector, and had his right hand stamped with invisible ink. He had brought a package of Christmas cards, socks, and a hat from his Canadian guardians but was not allowed to deliver it because all packages have to come through the mailroom, where they are opened and inspected. Lesra registered and was given a number, but as he passed through the prison in single file, he was jarred by the guards’ shrill orders.

“Get back in line!”

“Don’t speak to the person in front of you!”

“Have your ID ready!”

“Put your things in your locker!”

As Lesra stood in the waiting room, he finally heard “four-five-four-seven-two, up!”

That was Carter’s prison number. Lesra waited before a dim holding bay. As the steel doors opened and visitors began walking in, several women took deep breaths while others held hands. A guard checked the right hand of each visitor with a blue fluorescent light. After about twenty people filed in, the guard yelled, “Bay secure!” The doors shut, and there was a long moment of helplessness, of captivity. Then doors on the other side opened, and everyone moved out. The experience dazed Lesra, who had arrived wanting to cheer up a prisoner but was made to feel as if he had done something wrong himself.

Rubin Carter understood the feeling.

“You must be Lesra,” Carter said. He saw a frightened but good-looking young man about six inches shorter than he. (Carter was only five foot eight.) The prisoner’s appearance stunned the teenager. Every picture Lesra had seen of Carter showed him with a clean-shaven head, a thick goatee, and a menacing stare. Now he had a full Afro, a mustache, and a smile. The two embraced, then walked to the cell Carter had reserved. They sat facing each other and leaned forward so passing guards could not hear their conversation.

Lesra recounted his harrowing experience getting to the Visiting Center. “How do you survive in here?” he asked.

“I don’t acknowledge the existence of the prison,” Carter said. “It doesn’t exist for me.”

Lesra noticed that the guards patrolling the corridor did not walk as closely to their cell as to other cells, giving them a bit more privacy as a sign of respect. Lesra also heard inmates as well as guards refer to Rubin as “Mr. Carter.” When Lesra called him “Mr. Carter,” he laughed. “You can call me Rubin, or better yet, Rube.” As the inmate explained his refusal to participate in prison activities, Lesra remembered the words of Bob Dylan’s song “Hurricane,” which had been released in 1975 amid an outpouring of celebrity support:

But then they took him to a jailhouse

Where they tried to turn a man into a mouse.

The jailhouse, Lesra realized, had failed.

He described how he left his home in Bedford-Stuyvesant and moved to Toronto, where his new Canadian family was educating him. The arrangement puzzled Carter, and he told Lesra he need not worry about being alone. “I know they’re treating you well because of your smile, but if you’re ever not happy there, you let me know,” he said. The young man gave him the phone number to his home in Canada.

Читать дальше