The summer of 1967 was the worst of the decade’s “red hot summers.” From April through August, violence raged in 128 cities from Jersey City to Omaha, from Nashville to Phoenix. The most destructive conflagrations erupted in Newark, where 26 people were killed, and Detroit, where 43 perished. In all, 164 disorders resulted in 83 deaths, 1,900 injuries, and property damage totaling hundreds of millions of dollars.

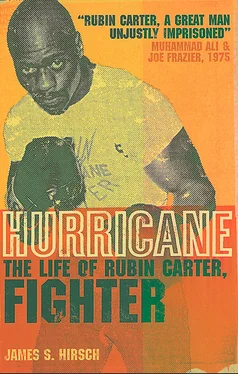

But Paterson remained calm. The convictions of Rubin Carter and John Artis brought to a close the worst crime in the city’s history. Judge Larner, noting Carter’s “antisocial behavior in past years,” sentenced him to three life sentences, two consecutive and one concurrent. Artis, as a first-time offender, received three concurrent life sentences. The only thing that surprised Carter was that the jury did not recommend the electric chair. Why would a white jury spare the life of two black men found guilty of such a barbaric act? Mercy? Shit! They’ve fried niggers for less . Maybe the jury felt pity for Artis and thus spared them both from the chair. Maybe the jury had doubts about their guilt. It didn’t matter—not now, not ever. One lie covers the world , Carter thought, before truth can get its boots on .

* Even with Carter in jail, Wegner lost to the reform candidate, Lawrence Kramer.

* In a letter to Governor Richard Hughes in 1968, F. Lee Bailey, who represented Matzner, wrote: “I have never, in any state or federal court, seen abuses of justice, legal ethics, and constitutional rights such as this case has involved.”

TRENTON STATE PRISON did not tolerate dissidents. The gray maximum-security monolith ran according to an intractable set of rules that completely controlled its captives’ lives. Prison guards often said: “The state always wins,” meaning, rebellious prisoners ultimately comply. Rubin Carter would test that motto unlike any other inmate in New Jersey’s history. But opposition to authority was nothing new for him. It was, in fact, his nature.

Born on May 6, 1937, in the Passaic County town of Delawanna, Carter learned early on that the men in his family are not intimidated by threats. His father was one of thirteen brothers who all grew up on a cotton farm in Georgia. According to family lore, one brother, Marshall, was once seen fraternizing with a white woman. Panic surged through the house as word arrived that the Ku Klux Klan planned to crash the Carter home. The boys’ father, Thomas Carter, sent several of his sons to Philadelphia, instructing them to return with fifteen guns—one for each member of the family. The Klan arrived, but the Carters, fortified with weapons, stood their ground, and the hooded riders retreated. Shortly thereafter, the family packed up and moved to New Jersey—although each brother would return to Georgia to select a bride.

The Klan story, no doubt embellished over the years, impressed on Rubin the importance of family pride and unity. His father, Lloyd, also regaled his seven children with stories of tobacco-chewing crackers in the South hunting down black men, then tarring or hanging them. On cold nights at home, Lloyd Carter told these stories around a coal-stoked burner as his children ate roasted peanuts sent by relatives in the South. Rubin, in stocking feet, would stretch his legs toward the crackling stove and let his mind race through the Georgia swamps, chased by whooping rednecks and howling dogs. The specter scared him, but he felt protected by the closeness of his family.

When Rubin was six, the Carters moved to Paterson, to a stable, racially mixed neighborhood known as “up the hill”—a few blocks away from poorer residents, who were literally “down the hill.” Lloyd Carter made good money with his various business enterprises. He traded in for a new car every two or three years, and the Carters were the first black family in the neighborhood to own a television. But working two jobs six days a week—Sundays were for praying—wore him down, and his wife, Bertha, worried about his health. A lean, strong, bespectacled man just under six feet tall, Lloyd defended himself by quoting the Holy Scriptures. “Bert,” he said, “‘whatsoever thy hand findeth to do, do it with thy might; for there is no work, nor device, nor knowledge, nor wisdom, in the grave, whither thou goest.’”

Lloyd Carter also disciplined his children with a religious zeal. A deacon in his Baptist church, he forbade the children from playing records or cards at home. Listening to the radio or dancing in the house was also prohibited. While he spoke softly, he carried a hard switch, and Rubin gave his father ample reason to use it.

The boy’s penchant for fighting often earned him swift punishment, but Rubin felt he had good reason to fight. He stuttered severely, stomping his foot on the ground to push the words out, and bitterly fought any kid who teased him for this impediment. His father had stammered as a youth, and his father had struck him with a calf’s kidney to try to cure him. Somehow Lloyd did overcome his speech problem, but he didn’t give his son much help. On the contrary, Rubin’s parents believed an old wives’ tale that severe stuttering indicated that the speaker was lying, which meant Rubin seemed unable to tell the truth. His response was to avoid talking, but that fueled the perception that he was stupid. To compensate for his stumbling tongue, the boy excelled in physical activities. He was muscular, fast, and fearless, and he saw himself as a protector of other people, particularly his siblings.

His brother Jimmy, for example, was two years older than Rubin, but he was studious, quiet, and prone to illness. When the Carters lived in Delawanna, Jimmy was sent to the basement to fetch coal from the family bin, but a neighborhood bully who was stealing the coal beat him up in the process. With his parents off at work, Rubin went to the basement himself to avenge the Carter name. It was his first fight. As he later wrote:

A shiver of fierce pleasure ran through me. It was not spiritual, this thing that I felt, but a physical sensation in the pit of my stomach that kept shooting upward through every nerve until I could clamp my teeth on it. Every time Bully made a wrong turn, I was right there to plant my fist in his mouth. After a few minutes of this treatment, the cellar became too hot for Bully to handle, and he made it out the door, smoking.

Bullies were not the only victims of Rubin’s wrath. In a Paterson grammar school, he once looked out his classroom door and saw a male teacher chasing his younger sister Rosalie down the hall. He raced out the door, tackled the teacher, and began swinging. The school expelled Rubin, prompting his father to beat him with a belt. But the beatings at home did not deter the boy, who continued to lash out at most anyone, even a black preacher who lived in the neighborhood. He owned a two-family home, and when he saw Rubin, at the age of ten, flirting with a girl who also lived in the house, he shooed him off the porch. But Rubin punched back with all his strength. The dazed preacher reported the incident to Rubin’s father, who stripped his son, tied him up, and whipped him.

Lloyd Carter feared that his son’s pugnacity would cost him his life one day, specifically at the hands of whites, and that fear led to a searing childhood incident. Each summer, Lloyd and his brothers drove their families in a caravan from New Jersey to Georgia, where they stayed with relatives, worked on farms, told stories, and sang and prayed together. On one occasion after church, some cotton farmers gathered in a grove to sing and picnic. A white man selling ice cream bars stopped nearby, and children carrying dimes raced to get a treat. Rubin had barely torn his wrapper when his father landed a heavy blow on his face, sending Rubin and the ice cream in opposite directions. Lloyd Carter never said why he struck his son; years later Rubin realized that his father feared white men, and he wanted his son to feel that same fright as well. Instead, the nine-year-old, his face puffed and bruised, came away with a very different lesson. He had taken his father’s best shot, and now he no longer feared the man. Moreover, Rubin determined that he was never going to let another person hurt him again. Not his father, not a police officer, not a prison guard, not a mayor, not a bum. Nobody.

Читать дальше