Dedication THE LAST KINGDOM is for Judy, with love Wyrd bið ful ãræd

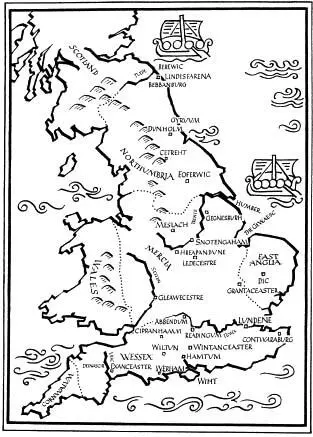

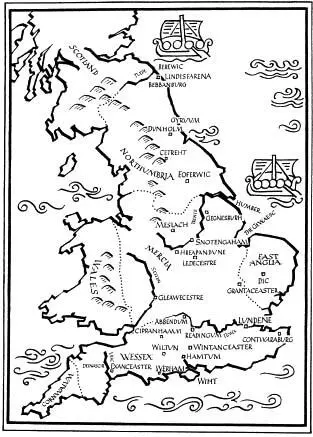

Map

Place-names

Prologue: NORTHUMBRIA, 866–867 AD

Part One: A PAGAN CHILDHOOD

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Part Two: THE LAST KINGDOM

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Part Three: THE SHIELD WALL

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Historical Note

The spelling of place-names in Anglo-Saxon England was an uncertain business, with no consistency and no agreement even about the name itself. Thus London was variously rendered as Lundonia, Lundenberg, Lundenne, Lundene, Lundenwic, Lundenceaster and Lundres. Doubtless some readers will prefer other versions of the names listed below, but I have usually employed whatever spelling is cited in the Oxford Dictionary of English Place-Names for the years nearest or contained within Alfred’s reign, 871–899 AD, but even that solution is not foolproof. Hayling Island, in 956, was written as both Heilincigae and Hæglingaiggæ. Nor have I been consistent myself; I have preferred the modern England to Englaland and, instead of Norðhymbralond, have used Northumbria to avoid the suggestion that the boundaries of the ancient kingdom coincide with those of the modern county. So this list, like the spellings themselves, is capricious:

| Æbbanduna |

Abingdon, Berkshire |

| Æsc’s Hill |

Ashdown, Berkshire |

| Baðum (pronounced Bathum) |

Bath, Avon |

| Basengas |

Basing, Hampshire |

| Beamfleot |

Benfleet, Essex |

| Beardastopol |

Barnstable, Devon |

| Bebbanburg |

Bamburgh Castle, Northumberland |

| Berewic |

Berwick-upon-Tweed, Northumberland |

| Berrocscire |

Berkshire |

| Blaland |

North Africa |

| Cantucton |

Cannington, Somerset |

| Cetreht |

Catterick, Yorkshire |

| Cippanhamm |

Chippenham, Wiltshire |

| Cirrenceastre |

Cirencester, Gloucestershire |

| Contwaraburg |

Canterbury, Kent |

| Cornwalum |

Cornwall |

| Cridianton |

Crediton, Devon |

| Cynuit |

Cynuit Hillfort, nr. Cannington, Somerset |

| Dalriada |

Western Scotland |

| Defnascir |

Devonshire |

| Deoraby |

Derby, Derbyshire |

| Dic |

Diss, Norfolk |

| Dunholm |

Durham, County Durham |

| Eoferwic |

York (also the Danish Jorvic, pronounced Yorvik) |

| Exanceaster |

Exeter, Devon |

| Fromtun |

Frampton on Severn, Gloucestershire |

| Gegnesburh |

Gainsborough, Lincolnshire |

| the Gewæsc |

The Wash |

| Gleawecestre |

Gloucester, Gloucestershire |

| Grantaceaster |

Cambridge, Cambridgeshire |

| Gyruum |

Jarrow, County Durham |

| Haithabu |

Hedeby, trading town in Southern Denmark |

| Hamanfunta |

Havant, Hampshire |

| Hamptonscir |

Hampshire |

| Hamtun |

Southampton, Hampshire |

| Heilincigae |

Hayling Island, Hampshire |

| Hreapandune |

Repton, Derbyshire |

| Kenet |

River Kennet |

| Ledecestre |

Leicester, Leicestershire |

| Lindisfarena |

Lindisfarne (Holy Island), Northumberland |

| Lundene |

London |

| Mereton |

Marten, Wiltshire |

| Meslach |

Matlock, Derbyshire |

| Pedredan |

River Parrett |

| Pictland |

Eastern Scotland |

| the Poole |

Poole Harbour, Dorset |

| Readingum |

Reading, Berkshire |

| Sæfern |

River Severn |

| Scireburnan |

Sherborne, Dorset |

| Snotengaham |

Nottingham, Nottinghamshire |

| Solente |

Solent |

| Streonshall |

Strensall, Yorkshire |

| Sumorsæte |

Somerset |

| Suth Seaxa |

Sussex (South Saxons) |

| Synningthwait |

Swinithwaite, Yorkshire |

| Temes |

River Thames |

| Thornsæta |

Dorset |

| Tine |

River Tyne |

| Trente |

River Trent |

| Tuede |

River Tweed |

| Twyfyrde |

Tiverton, Devon |

| Uisc |

River Exe |

| Werham |

Wareham, Dorset |

| Wiht |

Isle of Wight |

| Wiire |

River Wear |

| Wiltun |

Wilton, Wiltshire |

| Wiltunscir |

Wiltshire |

| Winburnan |

Wimborne Minster, Dorset |

| Wintanceaster |

Winchester, Hampshire |

PROLOGUE

Northumbria, 866–867 AD

My name is Uhtred. I am the son of Uhtred, who was the son of Uhtred and his father was also called Uhtred. My father’s clerk, a priest called Beocca, spelt it Utred. I do not know if that was how my father would have written it, for he could neither read nor write, but I can do both and sometimes I take the old parchments from their wooden chest and I see the name spelled Uhtred or Utred or Ughtred or Ootred. I look at those parchments which are deeds saying that Uhtred, son of Uhtred is the lawful and sole owner of the lands that are carefully marked by stones and by dykes, by oaks and by ash, by marsh and by sea, and I dream of those lands, wave-beaten and wild beneath the wind-driven sky. I dream, and know that one day I will take back the land from those who stole it from me.

I am an Ealdorman, though I call myself Earl Uhtred, which is the same thing, and the fading parchments are proof of what I own. The law says I own that land, and the law, we are told, is what makes us men under God instead of beasts in the ditch. But the law does not help me take back my land. The law wants compromise. The law thinks money will compensate for loss. The law, above all, fears the bloodfeud. But I am Uhtred, son of Uhtred, and this is the tale of a bloodfeud. It is a tale of how I will take from my enemy what the law says is mine. And it is the tale of a woman and of her father, a king.

He was my king and all that I have I owe to him. The food that I eat, the hall where I live and the swords of my men, all came from Alfred, my king, who hated me.

This story begins long before I met Alfred. It begins when I was nine years old and first saw the Danes. It was the year 866 and I was not called Uhtred then, but Osbert, for I was my father’s second son and it was the eldest who took the name Uhtred. My brother was seventeen then, tall and well-built, with our family’s fair hair and my father’s morose face.

The day I first saw the Danes we were riding along the sea shore with hawks on our wrists. There was my father, my father’s brother, my brother, myself and a dozen retainers. It was autumn. The sea-cliffs were thick with the last growth of summer, there were seals on the rocks, and a host of seabirds wheeling and shrieking, too many to let the hawks off their leashes. We rode till we came to the criss-crossing shallows that rippled between our land and Lindisfarena, the Holy Island, and I remember staring across the water at the broken walls of the abbey. The Danes had plundered it, but that had been many years before I was born, and though the monks were living there again the monastery had never regained its former glory.

Читать дальше