THE FLAME BEARER

BERNARD CORNWELL

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it, while at times based on historical figures, are the work of the author’s imagination.

Published by HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperCollins Publishers 2016

Copyright © Bernard Cornwell 2016

Bernard Cornwell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2016

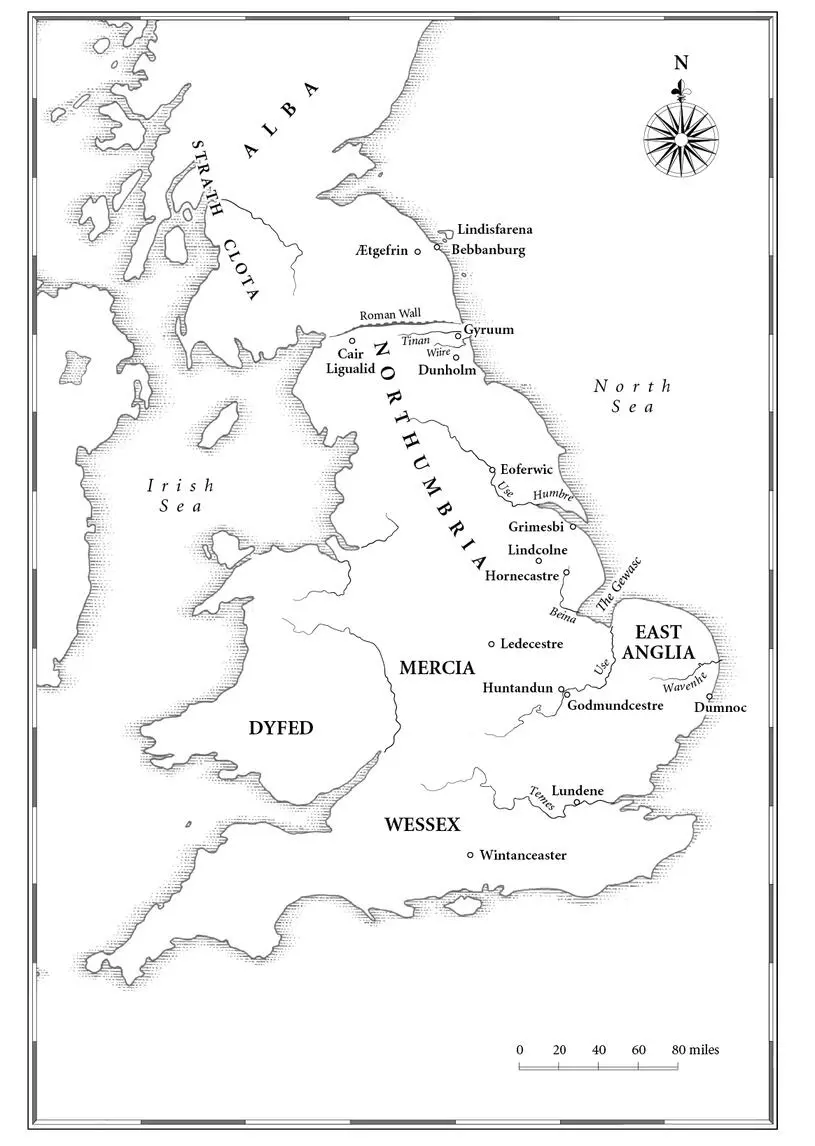

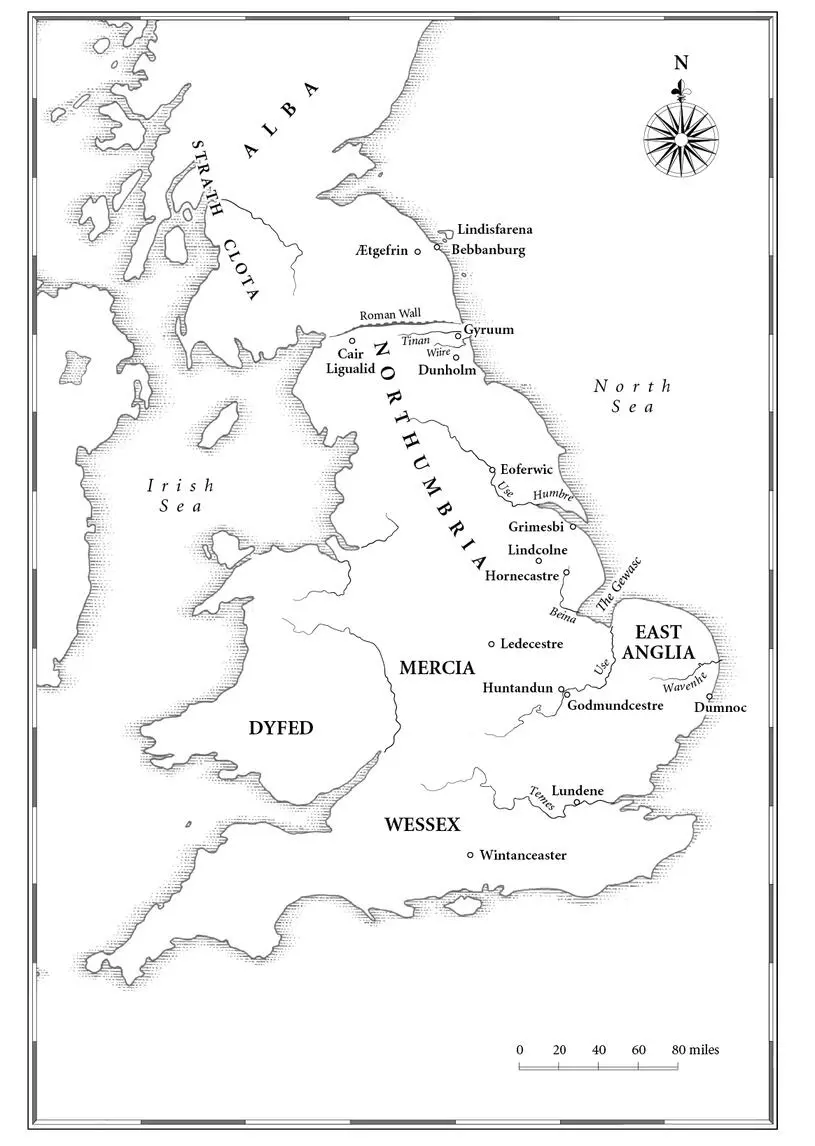

Map © John Gilkes 2016

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

Source ISBN: 9780007504251

Ebook Edition © 2016 ISBN: 9780007504237

Version: 2018-06-27

The Flame Bearer

is for Kevin Scott Callahan,

1992–2015

Wyrd bið ful ãræd

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Map

Place Names

Part One: The King

One

Two

Part Two: The Trap

Three

Four

Five

Six

Part Three: The Mad Bishop

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Part Four: The Return to Bebbanburg

Eleven

Twelve

Epilogue

Historical Note

Read on ...

About the Author

Also by Bernard Cornwell

About the Publisher

The spelling of place names in Anglo-Saxon England was an uncertain business, with no consistency and no agreement even about the name itself. Thus London was variously rendered as Lundonia, Lundenberg, Lundenne, Lundene, Lundenwic, Lundenceaster and Lundres. Doubtless some readers will prefer other versions of the names listed below, but I have usually employed whichever spelling is cited in either the Oxford Dictionary of English Place-Names or the Cambridge Dictionary of English Place-Names for the years nearest or contained within Alfred’s reign, AD 871–899, but even that solution is not foolproof. Hayling Island, in 956, was written as both Heilincigae and Hæglingaiggæ. Nor have I been consistent myself; I have preferred the modern form Northumbria to Norðhymbralond to avoid the suggestion that the boundaries of the ancient kingdom coincide with those of the modern county. So this list, like the spellings, is capricious.

| Ætgefrin |

Yeavering Bell, Northumberland |

| Alba |

A kingdom comprising much of modern Scotland |

| Beamfleot |

Benfleet, Essex |

| Bebbanburg |

Bamburgh, Northumberland |

| Beina |

River Bain |

| Cair Ligualid |

Carlisle, Cumbria |

| Ceaster |

Chester, Cheshire |

| Cirrenceastre |

Cirencester, Gloucestershire |

| Cocuedes |

Coquet Island, Northumberland |

| Contwaraburg |

Canterbury, Kent |

| Dumnoc |

Dunwich, Suffolk (now mostly vanished beneath |

|

the sea) |

| Dunholm |

Durham, County Durham |

| Eoferwic |

York, Yorkshire |

| (Danish name: Jorvik) |

|

| Ethandun |

Edington, Wiltshire |

| The Gewasc |

The Wash |

| Godmundcestre |

Godmanchester, Cambridgeshire |

| Grimesbi |

Grimsby, Humberside |

| Gyruum |

Jarrow, Tyne & Wear |

| Hornecastre |

Horncastle, Lincolnshire |

| Humbre |

River Humber |

| Huntandun |

Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire |

| Ledecestre |

Leicester, Leicestershire |

| Lindcolne |

Lincoln, Lincolnshire |

| Lindisfarena |

Lindisfarne (Holy Island), Northumberland |

| Lundene |

London |

| Mældunesburh |

Malmesbury, Wiltshire |

| Steanford |

Stamford, Lincolnshire |

| Strath Clota |

Strathclyde |

| Sumorsæte |

Somerset |

| Tinan |

River Tyne |

| Use |

River Ouse (Northumbria), also Great Ouse (East |

|

Anglia) |

| Wavenhe |

River Waveney |

| Weallbyrig |

Fictional name for a fort on Hadrian’s Wall |

| Wiire |

River Wear |

| Wiltunscir |

Wiltshire |

| Wintanceaster |

Winchester, Hampshire |

It began with three ships.

Now there were four.

The three ships had come to the Northumbrian coast when I was a child, and within days my elder brother was dead and within weeks my father had followed him to the grave, my uncle had stolen my land and I had become an exile. Now, so many years later, I was on the same beach watching four ships come to the coast.

They came from the north, and anything that comes from the north is bad news. The north brings frost and ice, Norsemen and Scots. It brings enemies, and I had enemies enough already because I had come to Northumbria to recapture Bebbanburg. I had come to kill my cousin who had usurped my place. I had come to take my home back.

Bebbanburg lay to the south. I could not see the ramparts from where our horses stood because the dunes were too high, but I could see smoke from the fortress’s hearths being snatched westward by the wild wind. The smoke was being blown inland, melding with the low grey clouds that scudded towards Northumbria’s dark hills.

It was a sharp wind. The sand flats that stretched towards Lindisfarena were riotous with breaking waves that seethed white and fast towards the shore. Further out the waves were foam-capped, their spume flying, turbulent. It was also bitterly cold. Summer might have just come to Britain, but winter still wielded a keen-edged knife on the Northumbrian coast and I was glad of my bearskin cloak.

‘A bad day for sailors,’ Berg called to me. He was one of my younger men, a Norse who revelled in his skill as a swordsman. He had grown his long hair even longer in the last year until it flared out like a great horsetail beneath the rim of his helmet. I had once seen a Saxon seize a man’s long hair and drag him backwards from his saddle, then spear him while he was still flailing on the turf.

Читать дальше