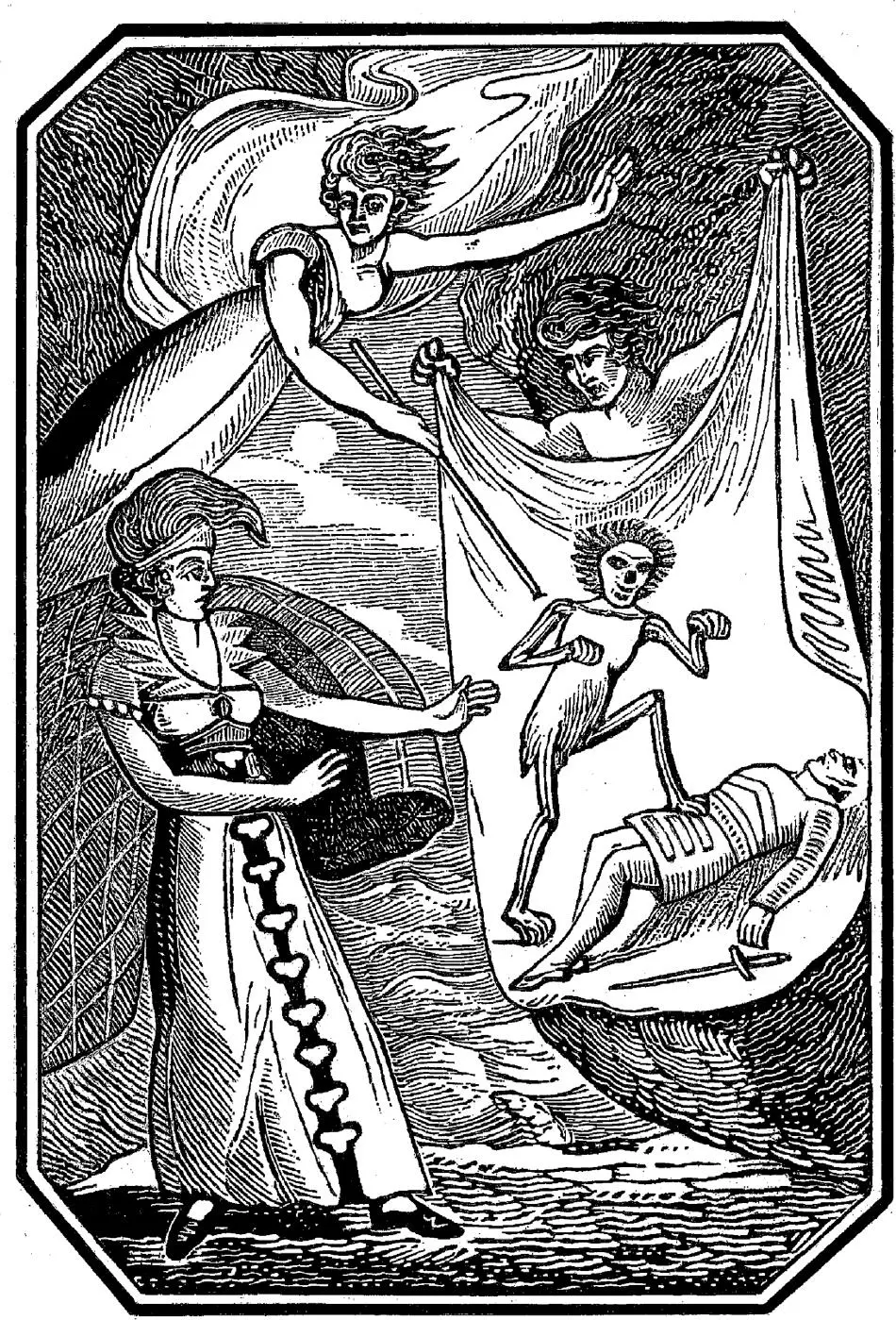

The frontispiece from the 1820 edition of ‘The Bride of the Isles’.

HARPER

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Publishers 2017

Selection, Introduction, and Notes © Richard Dalby and Brian J. Frost 2017

Cover design and illustration by Mike Topping © HarperCollins Publishers Ltd 2017

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008216481

Ebook Edition © May 2017 ISBN: 9780008216498

Version: 2017-04-05

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

The Bride of the Isles by Anonymous (1820)

The Unholy Compact Abjured by Charles Pigault-Lebrun (1825)

Viy by Nikolai Gogol (1835)

The Burgomaster in Bottle by Erckmann-Chatrian (1849)

Lost in a Pyramid; or, The Mummy’s Curse by Louisa May Alcott (1869)

Professor Brankel’s Secret by Fergus Hume (1882)

John Barrington Cowles by Arthur Conan Doyle (1884)

Manor by Karl Heinrich Ulrichs (1884)

Old Aeson by Arthur Quiller-Couch (1890)

The Mask by Richard Marsh (1892)

The Last of the Vampires by Phil Robinson (1893)

The Story of Jella and the Macic by Professor P. Jones (1895)

The Ring of Knowledge by William Beer (1896)

A Beautiful Vampire by Arabella Kenealy (1896)

The Story of Baelbrow by E. & H. Heron (1898)

The Purple Terror by Fred M. White (1899)

Glámr by Sabine Baring-Gould (1904)

The Vampire Nemesis by ‘Dolly’ (1905)

The Electric Vampire by F. H. Power (1910)

Footnotes

Bibliography

About the Editors

By the Same Editor

About the Publisher

ARRANGED chronologically, the nineteen stories in this anthology are culled from books and magazines published between 1820 and 1910, a period noted for producing some of the finest vampire tales ever written. The first vampire story to make a significant impact on European literature was ‘The Vampyre,’ by John William Polidori, which set a precedent by depicting the vampire as an aristocrat. Erroneously attributed to Lord Byron when it was first published in the April 1819 issue of The New Monthly Magazine , this story subsequently inspired a surge of popular interest in vampires and established the vampire’s image as a fatal lover.

In 1820 the French author Cyprien Bérard penned a novel-length sequel to Polidori’s story, titling it Lord Ruthwen ou les Vampires . This, in turn, formed the basis for James R. Planché’s play The Vampire; or, The Bride of the Isles , which had its first performance on the London stage in August 1820. Not long afterwards an anonymously-written short story adapted from the play, bearing the title ‘The Bride of the Isles: A Tale Founded on the Popular Legend of the Vampire,’ was put on sale by an enterprising Dublin publisher. Better than most vampire tales written in the early 1800s, its inclusion in the present volume marks its first appearance in an anthology exclusively devoted to vampire fiction.

The earliest known vampire story by an American writer, Robert C. Sands’ ‘The Black Vampyre: A Legend of Saint Domingo’ (1819), broke new ground by featuring a mulatto vampire. A more significant innovation, the introduction of the female vampire into prose fiction, is the main claim to fame of Ernst Raupach’s ‘Wake Not the Dead,’ which was, for many years, falsely attributed to Johann Ludwig Tieck. A cautionary tale about the folly of bringing the dead back to life, it was originally published in Leipzig in 1822, and received its first English translation a year later when it was included in Popular Tales and Romances of the Northern Nations . Less well-known is the quaintly titled story ‘Pepopukin in Corsica,’ in which a disagreeable suitor is sent packing by inspiring in him a dread of vampires. Originally published in 1827, in The Stanley Tales, Vol. 1 , where it was credited to ‘A. Y.’, it was recently claimed that the author these initials belonged to was Arthur Young. Another story from the 1820s, this time by a French writer, is ‘The Unholy Compact Abjured’ (1825), by Charles Pigault-Lebrun, in which a soldier seeking shelter for the night encounters demonic vampires in a spooky chateau.

Russian literature’s first major contribution to the vampire canon was Nikolai Gogol’s ‘Viy,’ which comes from his 1835 collection Mirgorod . Described by Edmund Wilson as ‘one of the most terrific things of its kind ever written,’ it is about a young philosopher’s frightening encounter with a witch-vampire and monstrous winged creatures under the control of the King of the Gnomes. The most famous vampire story from the 1830s is undoubtedly ‘La Morte Amoureuse’ (1836), by the French author Théophile Gautier. Anthologised many times under different titles (e.g. ‘Clarimonde,’ ‘The Dreamland Bride,’ and ‘The Beautiful Dead’), it tells of a young priest’s illicit relationship with a dead courtesan, whose beguiling revenant draws him into a fantastical dreamworld and nightly sucks small quantities of his blood to sustain her life-in-death existence.

Meanwhile, in America, Edgar Allan Poe was turning out a string of morbid horror tales, several of which dealt with unusual forms of vampirism. In ‘Ligeia’ (1838), for instance, he introduced the idea of mental vampirism, linking it with the allied theme of metempsychosis. The ill-fated title character, a beautiful, highly intelligent woman, gradually wastes away as a result of her husband’s obsessive desire to know her completely; but, in a final twist, retribution for this subconscious act of vampirism seems likely when the dead woman’s spirit possesses the body of her marital successor, suggesting that the roles of vampire and victim will shortly be reversed. A variation on the same theme occurs in another of Poe’s stories, ‘The Oval Portrait’ (1845), in which an artist totally absorbed in capturing an absolute likeness of his lovely young bride is unaware of the devitalising effect it is having on her frail constitution, and fails to notice that with each sitting the woman’s life force is ebbing away. Psychic vampirism of an even more bizarre kind is the underlying theme of Poe’s masterpiece, ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’ (1839). In this story the psychic vampire is the ancestral home of the Usher family, and its victims are the current occupants, Roderick Usher and his sister Madeline. By some hideous process, the ancient mansion – a sentient stone organism impregnated with the evil emanations of past generations of Ushers – is having a devitalising effect on the doomed couple, bringing the horror of madness into their lives. These three stories, along with two others utilising the vampire theme, ‘Morella’ (1835) and ‘Berenice’ (1835), were collected together in Dead Brides: Vampire Tales (1999).

Читать дальше