Consequently his body of work has ever since been assessed and reassessed as the greatest contribution to English literature. That is despite the fact that we know that different printers took it upon themselves to heavily edit the material they worked from. We also know that Elizabethan plays were worked and reworked frequently, so that they evolved over time until they were honed to perfection, which means that many different hands played their part in the active writing process. It would therefore be fair to say that any play attributed to Shakespeare is unlikely to contain a great deal of original input. Even the plots were based on well known historical events, so it would be hard to know what fragments of any Shakespeare play came from that single mind.

One might draw a comparison with the Christian bible, which remains such a compelling read because it came from the collaboration of many contributors and translators over centuries, who each adjusted the stories until they could no longer be improved. As virtually nothing is known of Shakespeare’s life and even less about his method of working, we shall never know the truth about his plays. They certainly contain some very elegant phrasing, clever plot devices and plenty of words never before seen in print, but as to whether Shakespeare invented them from a unique imagination or whether he simply took them from others around him is anyone’s guess.

The best bet seems to be that Shakespeare probably took the lead role in devising the original drafts of the plays, but was open to collaboration from any source when it came to developing them into workable scripts for effective performances. He would have had to work closely with his fellow actors in rehearsals, thereby finding out where to edit, abridge, alter, reword and so on.

In turn, similar adjustments would have occurred in his absence, so that definitive versions of his plays never really existed. In effect Shakespeare was only responsible for providing the framework of plays, upon which others took liberties over time. This wasn’t helped by the fact that the English language itself was not definitive at that time either. The consequence was that people took it upon themselves to spell words however they pleased or to completely change words and phrasing to suit their own preferences.

It is easy to see then, that Shakespeare’s plays were always going to have lives of their own, mutating and distorting in detail like Chinese whispers. The culture of creative preservation was simply not established in Elizabethan England. Creative ownership of Shakespeare’s plays was lost to him as soon as he released them into the consciousness of others. They saw nothing wrong with taking his ideas and running with them, because no one had ever suggested that one shouldn’t, and Shakespeare probably regarded his work in the same way. His plays weren’t sacrosanct works of art, they were templates for theatre folk to make their livings from, so they had every right to mould them into productions that drew in the crowds as effectively as possible. Shakespeare was like the helmsman of a sailing ship, steering the vessel but wholly reliant on the team work of his crew to arrive at the desired destination.

It seems that Shakespeare certainly had a natural gift, but the genius of his plays may be attributable to the collective efforts of Shakespeare and others. It is a rather satisfying notion to think that his plays might actually be the creative outpourings of the Elizabethan milieu in which Shakespeare immersed himself. That makes them important social documents as well as seminal works of the English language.

Money in Shakespeare’s Day

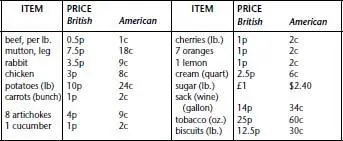

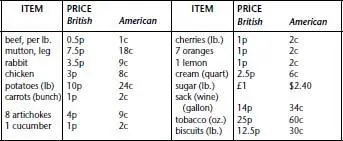

It is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to relate the value of money in our time to its value in another age and to compare prices of commodities today and in the past. Many items are simply not comparable on grounds of quality or serviceability.

There was a bewildering variety of coins in use in Elizabethan England. As nearly all English and European coins were gold or silver, they had intrinsic value apart from their official value. This meant that foreign coins circulated freely in England and were officially recognized, for example the French crown (écu) worth about 30p (72 cents), and the Spanish ducat worth about 33p (79 cents). The following table shows some of the coins mentioned by Shakespeare and their relation to one another.

A comparison of the following prices in Shakespeare’s time with the prices of the same items today will give some idea of the change in the value of money.

Michael Bogdanov’s modern-dress production of The Taming of the Shrew in 1979 was well received in terms of its theatrical competence but a number of critics felt that however well done, it had better not been done at all. Michael Billington in the Guardian doubted that there was any reason to revive a play ‘that seems totally offensive to our age and our society. My own feeling is that it should be put back firmly and squarely on the shelf’. Suggestions of censorship, as it were, have at least the merit of indicating that the offending object is being taken seriously, nor is Billington the first to find The Shrew a peculiarly damning blot on Shakespeare’s output: Shaw famously registered shame at ‘the lord-of-creation moral implied in the wager and the speech put into the woman’s own mouth’. The Shrew has generally proved a bit of a facer for those who would claim that Shakespeare is a great universal genius with ideas that transcend the limitations of his time. Hence the tendency of modern readings and productions either to imply that Shakespeare did not really acquiesce in the apparent patriarchal assumptions of the taming plot (nor the reductiveness about female charm implied in Bianca’s defection from maidenly modesty), or to suggest that even if he did, the usefulness of the play for the twentieth century is to expose the latent misogyny and brutality that still form the real infrastructure of our bien pensant , politically correct culture.

One way of distancing Shakespeare from the implications of the taming plot has been to repair the broken frame of the play, increasing the significance of the Sly plot by importing material from the anonymous The Taming of a Shrew , printed in 1594 and possibly a ‘memorial reconstruction’ of a Shakespearean original. The taming and submission of Katherine can then be made to appear an unattainable and possibly rather vulgar male fantasy of domination, a dream of empowerment not unlike the violent fantasies of Pirate Jenny in Brecht’s Threepenny Opera . Alternatively, the play can be made to appear more coherent by privileging one or other of its generic modes. On the one hand by ignoring the incipient psychological complexity in the treatment of Katherine in particular (she is after all not the favoured child of her father and Bianca’s butter-wouldn’t-melt-in-her-mouth demeanour might irritate more than a shrew), and taking the whole as a farcical romp with no power to move or upset. On the other side, the farcical nastinesses can be played down in favour of modern notions of relationship where all is fair between the couple because they really love each other, win through to equality within properly constituted hierarchy, and are even, in the most sentimental versions of such a reading, complicit in Kate’s response to the wager.

Certainly H. J. Oliver in his introduction to the New Oxford edition of the play feels that Shakespeare’s not having provided a generically consistent play is a consequence of his youthfulness when he devised it – it is ‘a young dramatist’s attempt to mingle two genres that cannot be combined’. But if generic miscegenation is an effect of youth, then it is surprising to find it again in All’s Well That Ends Well and Measure for Measure . Since in these plays it does much to earn the description ‘problem plays’, it might be well to consider if this is not also the effect in The Shrew . The clash of farcical folk-tale in the taming plot with the legitimate desires of both Petruchio and Katherine for lives that they can live, betrays the inconsistences and half-truths that are daily tolerated and evaded. There seems to me no possible way of doubting that Shakespeare presents Katherine’s speech of submission to an idealised hierarchy of gender relationships without irony, but he surely does not do so without thought or without demonstrating the worst that can be said about its potential for physical and psychological tyranny.

Читать дальше