5. CORNISH HEATH

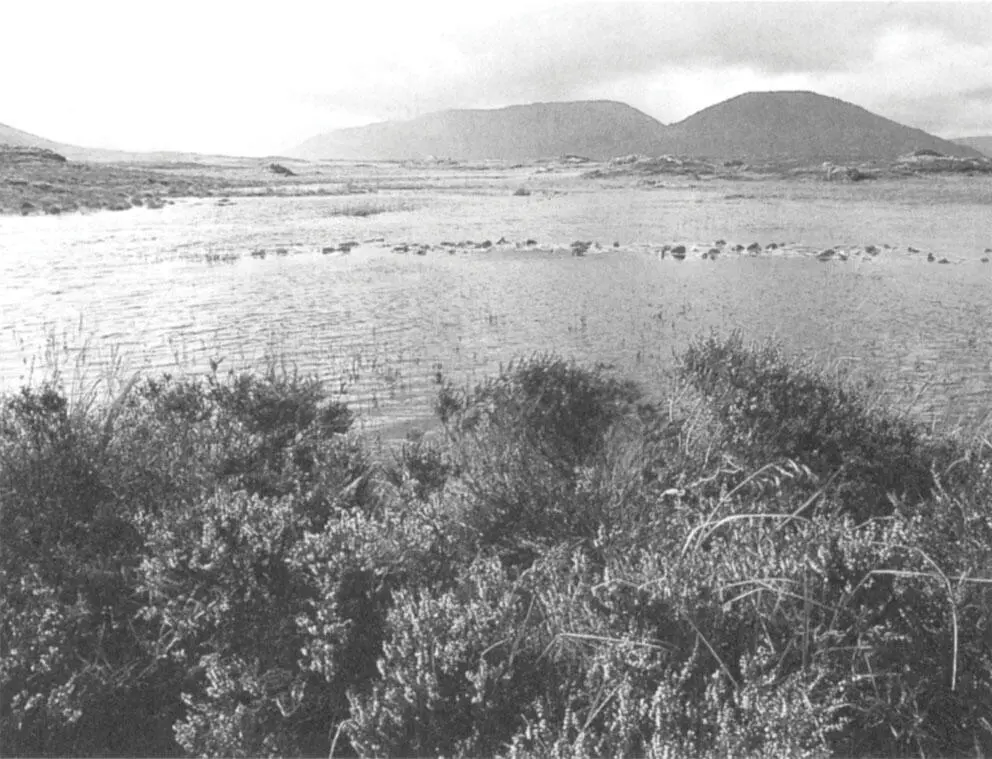

Originally found by Major Dickie of Enniskillen, but first reported by Praeger in 1938. 81It was growing on an isolated blanket bog near Belcoo, Co. Fermanagh, with white flowers (normally lilac-pink), and Praeger sided with those who considered the plant indigenous in a native habitat. Webb visited the bog in 1954 and reckoned that ‘the force of arguments were in favour of regarding it as native’. 82The site, close to a mineral flush, was visited in 1965 and 1966 by McClintock when about 1,000 plants were recorded. 83Another historical site was reported by Robert Burkitt in the 1850s, on the cliffs of Islandikane townland, west of Tramore, Co. Waterford, but the species has not been seen there since, despite repeated searches. It was naturalised on the sand hills at Dundrum, Co. Down, where it was discovered by Swanston in 1899, and was still present in 1978. 84It also grows on the rocky shore at Shane’s Castle, Co. Antrim. Outside Ireland it occurs in heaths in south Cornwall, and elsewhere in western Europe. It is a short to medium hairless undershrub with flowers ranging from white to pink to lilac. No evidence has yet been produced to show that Irish heath was a member of the Irish interglacial flora. Their seeds are consistently larger ( c .0.7 mm) compared with c. 0.5 mm of other Erica species, so it would have been difficult to overlook them in samples of interglacial deposits. 85

Irish heath with western gorse at Ballacragher Bay, Co. Mayo.

The Connemara and Burren plant assemblages

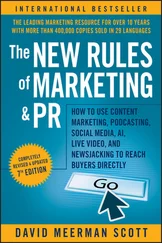

The congregation of the above ericaceous species in western Connemara is one example of apparent geographical plant madness, but the eclectic agglomeration of rare flowers in the Burren, Co. Clare, with representatives of arctic, alpine and Mediterranean floras also begs explanations. What could be the origin of such an unlikely association?

One interpretation postulates that these species originally had a more widespread range in Ireland. Although the Pleistocene glaciers probably wiped much of the landscape clean of living resources, some plants may have been able to avoid the ice blanket by moving up to the highest mountain peaks or sheltering in other refugia. Others, however, possibly shifted westwards to ice-free offshore islands and peninsulas. The sea level started to drop around 35,000 years ago, reaching its maximum fall of some 130 m below present day levels around 15,000 years ago. The west Clare and Connemara coastlines could then have extended perhaps some 45 and 10 km respectively west of today’s shorelines. 2Admiralty charts show commodious areas off the Burren coast stretching beyond the Aran Islands which would have been uncovered and well above water during the Ice Age. Assuming that the North Atlantic Current exercised some warming influence, the glaciers could not have impacted those areas. It is therefore possible that the plants may have survived in isolation on mist-shrouded, ice-free banks. As the glaciers withdrew and the sea started to rise again, the plants would have had to move back to the mainland. Despite the vegetative reproduction of most alpine species and presumed slow migration rates, the long time spans associated with the waxing and waning of the glaciers would have been sufficient to permit the relatively short migrations from the Burren and Connemara to those western tips and back again. Survival of plants during the first glacial epochs of the Ice Age on the summits of the Burren hills can probably be ruled out as all of them are too low to have escaped a scouring of the ice sheets (the highest is Slieve Elva at 344 m). However, several Burren hills were glacier-free during the last Midlandian glacial phase, towards the end of the Ice Age.

An alternative hypothesis regarding the survival of plants put forward by Mitchell & Ryan envisages a general migration of the various Burren and Connemara curiosities as well as other Lusitanian plant species up and down the western Atlantic seaboard from the Irish west coast to the shores of Spain and Portugal. In support of their western seaboard migration route hypothesis they quote the present known distribution of the shore-living bug Aepophilus bonnairei in Ireland, southern England, west Wales and the Isle of Man. Its modern day distribution centre is the Atlantic coast from Morocco to Portugal. If the bugs had been present in Ireland historically, they would not have survived the cold Nahanagan snap and must have ‘marched’ up along a western seaboard land bridge as temperatures rose some 10,000 years ago. Additional support for the southern route to Ireland for Lusitanian species comes from detailed pollen studies carried out by Fraser Mitchell, 2which show that pine, oak and alder followed the proposed route taken by Aepophilus across the ‘dry’ Bay of Biscay to the Celtic Sea and then into southern Ireland. However, the question of sea barriers and the long distances involved make this hypothesis less convincing. The introduction of seeds by migrating birds travelling northwards from Spain and Portugal is also improbable as most seeds of the Burren and Connemara curiosities are not eaten by birds.

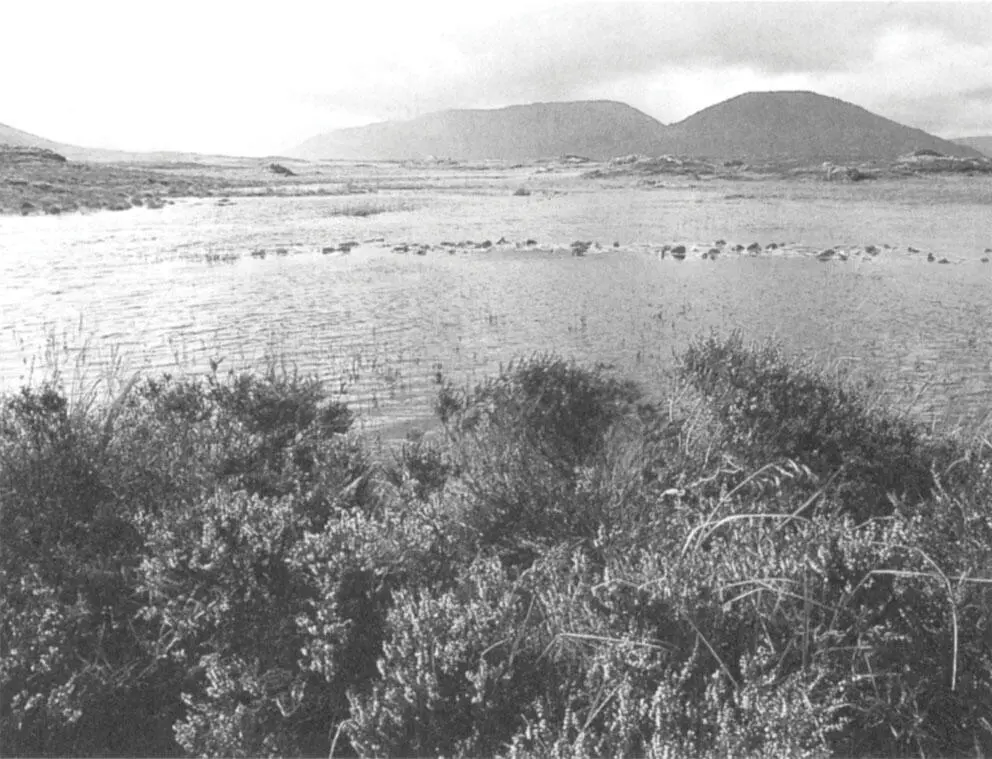

Western Connemara, Co. Galway, the location of rare plant assemblages.

Devoy has discussed five possible land bridge connections between Ireland and Britain, including the Continental shelf, across which flora and fauna could have moved into Ireland when the country was released from the grip of ice during the late Ice Age. 86Devoy considered that the route from the south, across the Continental shelf, along which the southern Lusitanian species would have travelled, would have been problematical. An interconnected series of channels and troughs off the south coast of Ireland led west and southwest into canyons lying at a greater depth than 100 m below today’s sea level. The movement of meltwaters and sediments over this area at the time even when sea levels were much lower than today would have created adverse conditions (pools, channels, rivers, etc.) for species sensitive to water, and made it very difficult, if not impossible, for plants to move dry-shod from Portugal, northern Spain and western France into Ireland. Thus the southern entry route for the so-called Lusitanian and other Mediterranean species now present in the Burren and in Connemara seems to be ruled out. Entry into Ireland of these species across the other four land bridges traversing what is now the Irish Sea is not supported by any historic or present day evidence. Survival of these species, many of which were already present in Ireland, in ice-free areas or refugia (off the west coast) thus appears to provide the most plausible explanation to account for the curiosities of Clare and Connemara.

The oceanic flora

The lowlier plants – ferns, mosses, liverworts and lichens – reproducing by minute, wind-blown spores, have less difficulty in crossing expanses of sea, and the mild, oceanic climate of Ireland has been particularly favourable to their colonisation. Especially in the extremely humid west, the profusion and luxuriance of these plants is a striking and important feature of the vegetation. In many of the western woods, communities of fìlmy-ferns, mosses and liverworts cover the rocky woodland floor and lower tree trunks, while lichens are most conspicuous on the upper trunks and branches. Many of these species have an extremely restricted European and even world distribution, confined to the far western seaboard and the Atlantic Isles of the Azores, Madeira and the Canaries (Macaronesia).

The most famous is the Killarney fern, much the largest and finest of our three fìlmy-ferns, once locally abundant along the rocky streams and in the lower corries of the southwestern mountains, but reduced to rarity by indiscriminate collecting. The moss-like Tunbridge and Wilson’s fìlmy-ferns are in amazing quantity in many rocky woodlands and shady block screes, while the hay-scented buckler-fern, with its distinctive crinkly fronds, grows large and in unusual quantity. Visitors from Britain are struck by the general abundance in western Ireland of the royal fern, often to be seen in great dense patches on peaty ground. The fern collectors made less impression on it here than in western Britain, where it was once also abundant in places. The Irish spleenwort is a very rare and beautiful fern of exposed dry rocks and banks in southern Ireland and is unknown in Britain, but another Mediterranean-Atlantic fern of similar habitats, the lanceolate spleenwort, is more frequent in western Britain than Ireland. The delicate maidenhair fern, a widespread species in warmer parts of the world, grows luxuriantly on limestone, especially in crevices of the Burren pavements. Also of interest are the liverworts Cephalozia hibernica, Lejeunea flava , L. hibernica and Radula holtii, found in Ireland but not in Britain (see Appendix 1).

Читать дальше