The largest continuous upland area in Ireland is in Co. Wicklow where the granite hills higher than 300 m range over 520 km 2and peak at 925 m on Lugnaquillia Mountain, which, unlike most of the other parts of the Wicklow uplands, has retained its Old Red Sandstone capping. The original body of the Wicklow Hills consisted of sandstones, grits and conglomerates that were laid down in an ancient sea during the Ordovician period. About 400 million years ago a large mass of hot molten granite was extruded from the earth’s belly. This heaving mass pushed the overlaying rocks upwards and humped them into a southwesterly aligned dome. Later on the sandstones and other slatey rocks were eroded away, a few lingering as marginal flanks to the hills, exposing the granite core that now forms the greatest area of granite in Ireland or Britain.

Further south in Cork and Kerry it is the hard Old Red Sandstone rocks that have endured. Their limestone covering was stripped off after all the rock layers were thrust up by a gigantic lateral earth movement some 300 million years ago, and folded in a series of ridges, aligned west-east. The intervening valleys, however, retain some of the surviving limestone. Towards the western side of this mountain mass are the Macgillycuddy’s Reeks, Co. Kerry. These host amongst a cluster of tall conical peaks, Ireland’s highest mountain, Carrauntoohil, rising to 1,039 m, to the east of which are the famous lakes and mountains of the Killarney National Park.

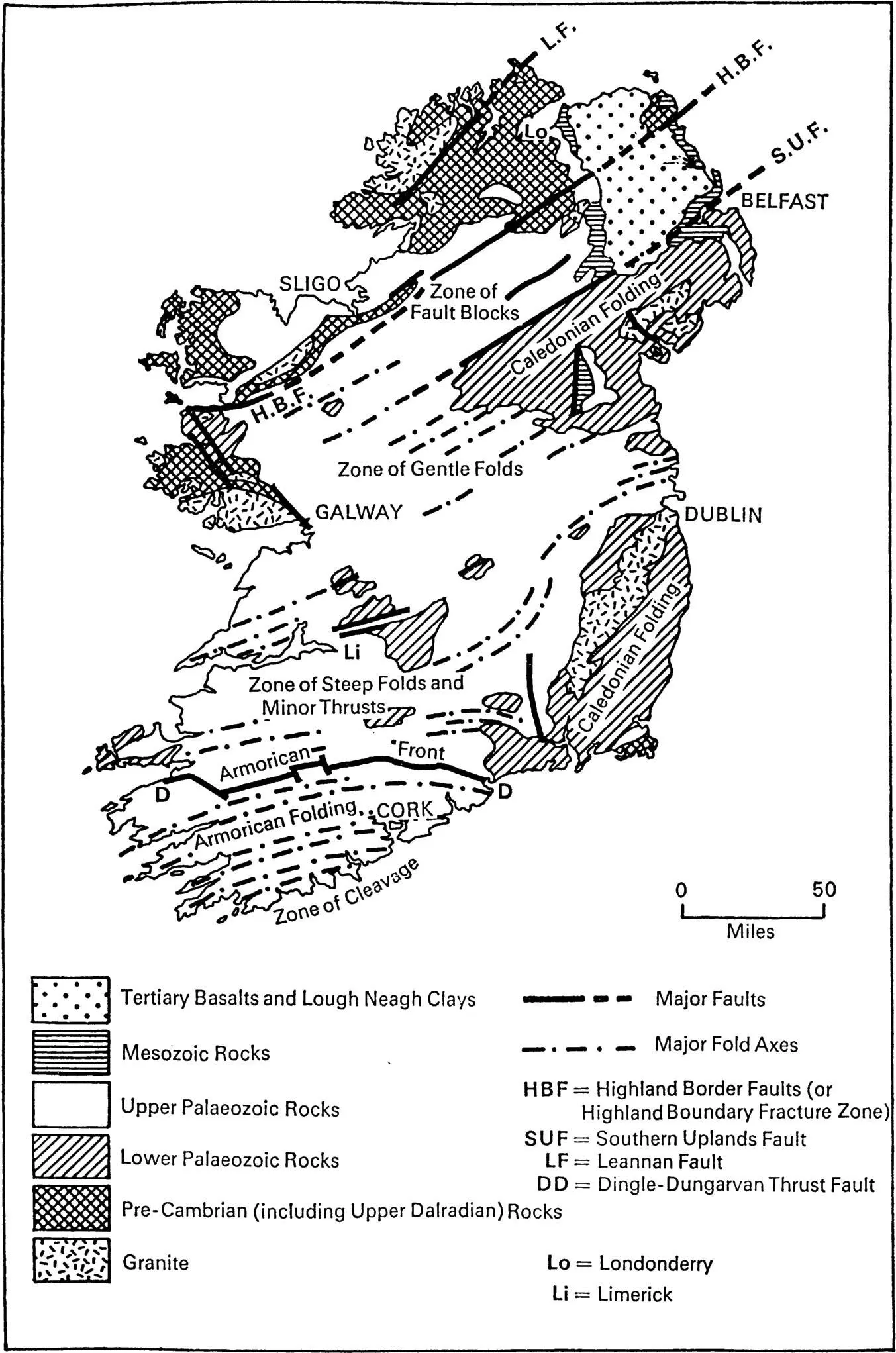

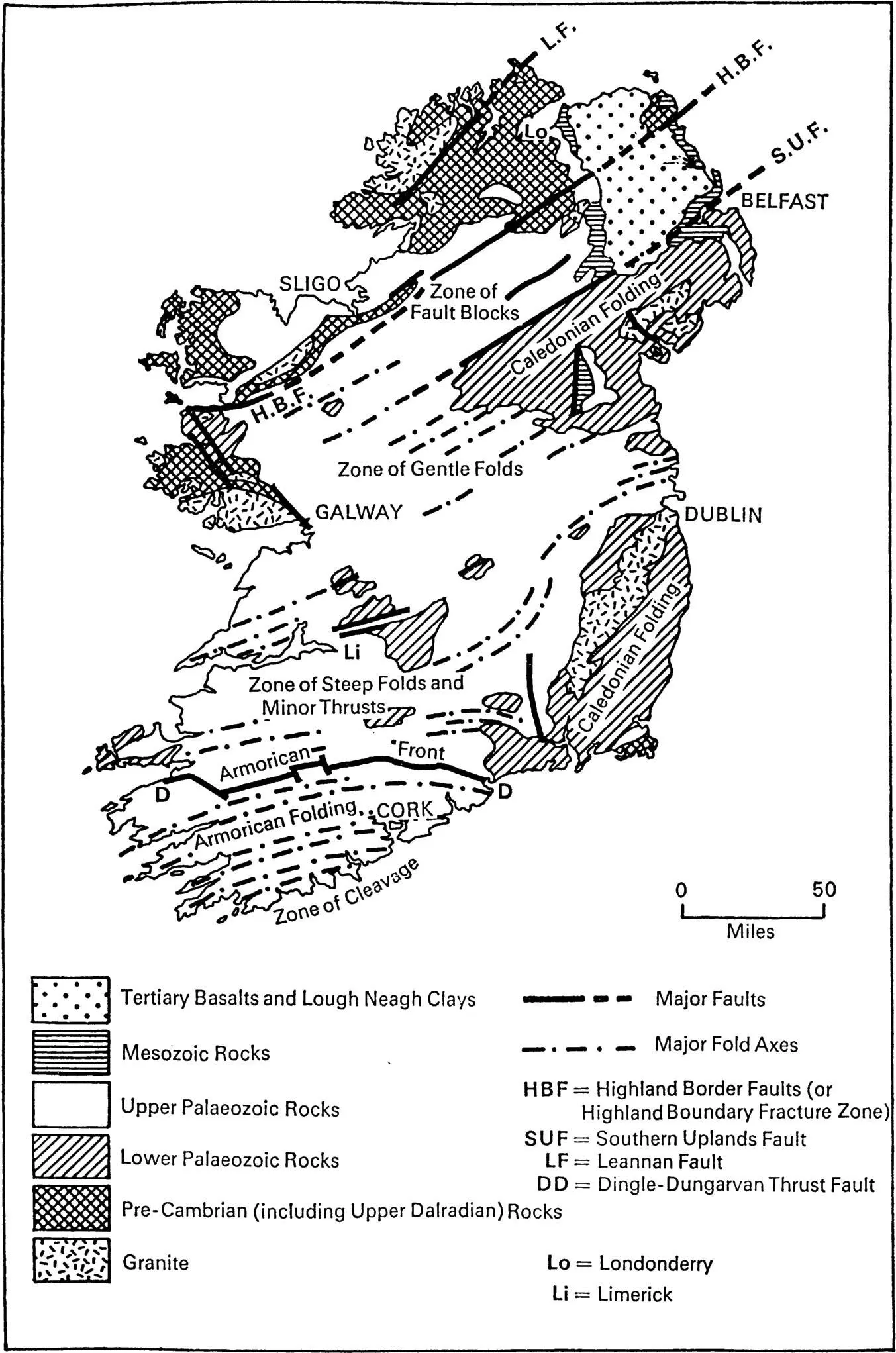

The structural geology of Ireland. From J.B. Whittow (1974) Geology and Scenery of Ireland. Penguin Books, London.

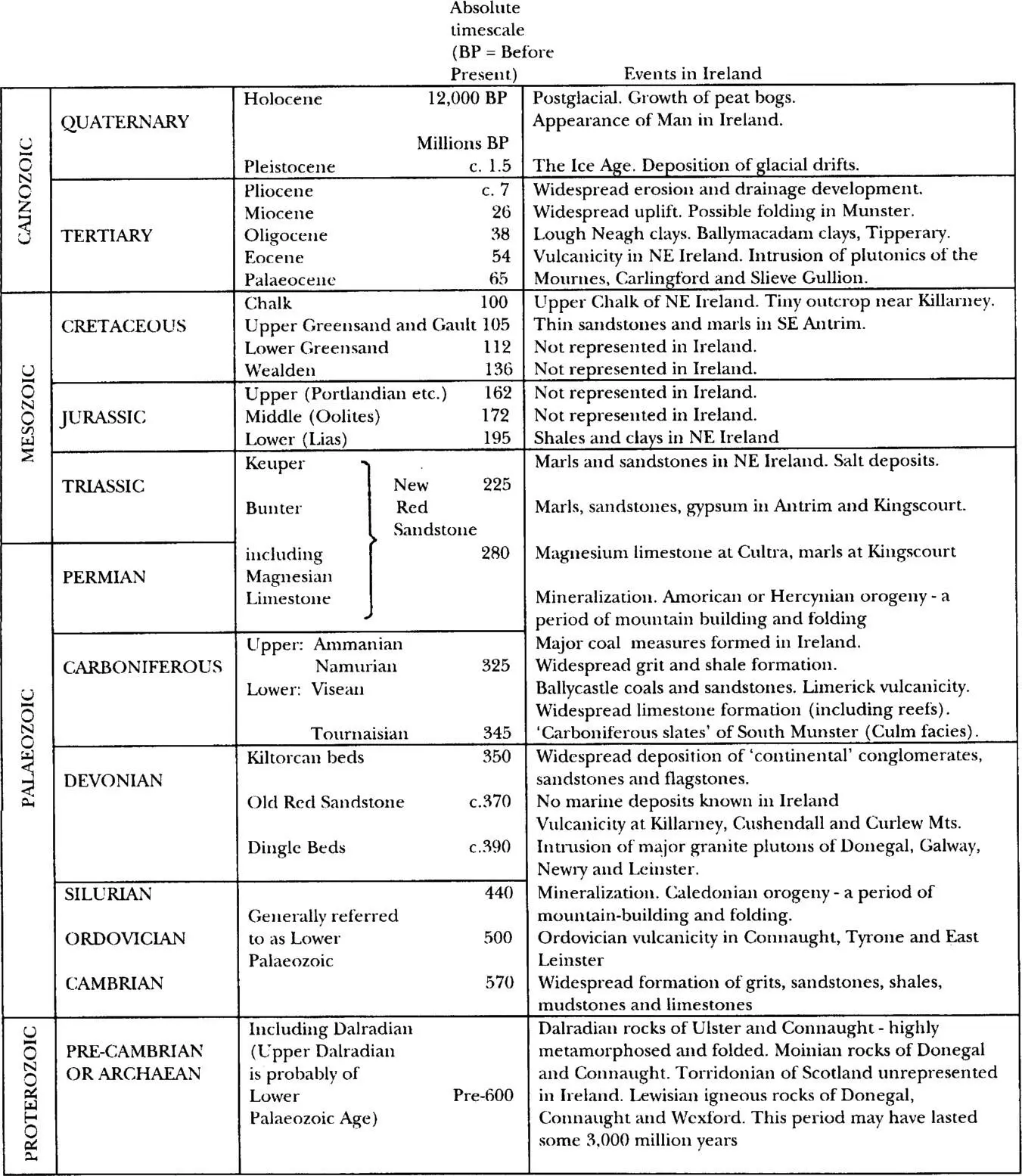

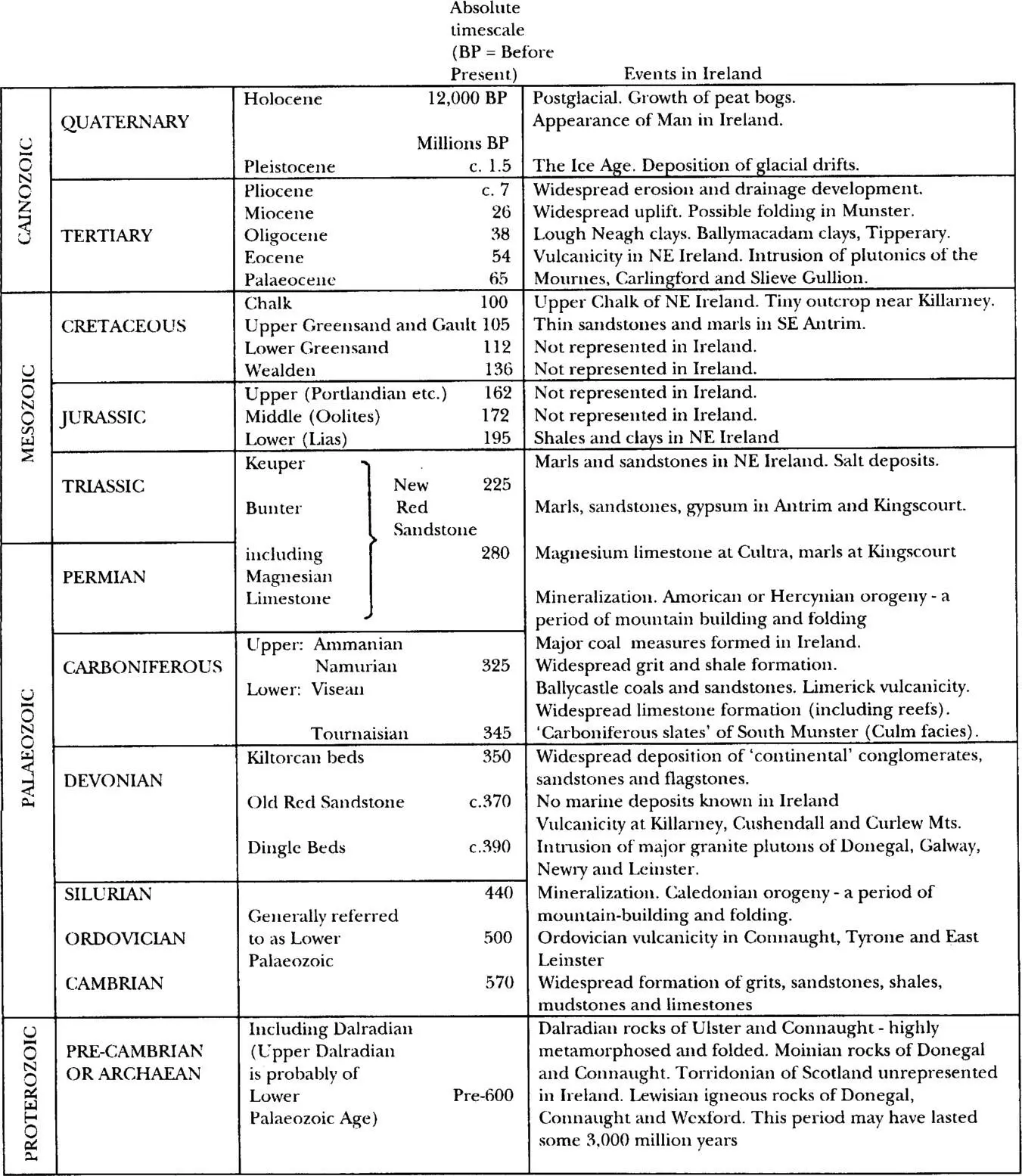

Table 3.1. Sequence of events and dates for the geological history of Ireland. From J.B. Whittow (1974) Geology and Scenery of Ireland. Penguin Books, London.

The Galway and Mayo highlands are also the result of convulsions that took place during the Caledonian mountain-building period some 400 million years ago. Hard granites in the south of Connemara and quartzites, gneiss, Silurian slates and shales in the north were pushed upwards to create hills and mountains. The Twelve Bens are made up of quartzite surrounded by Silurian schists and separated by valleys covered with blanket bog. Further north, over the Killary fjord, Co. Mayo, lies Mweelrea, the highest mountain in the west of Ireland (814 m), north of Brandon, Co. Kerry. The coastal cliffs at Slieve League, Co. Donegal, the highest sea cliffs within Ireland and Europe, plunge into the Atlantic from a height of 595 m. On the steep northeastern and landward face, one of the richest assemblages of alpine flora in Ireland looks out over blanket bogland and the cold, desolate Lough Agh below.

Rainfall, soil and environmental conditions

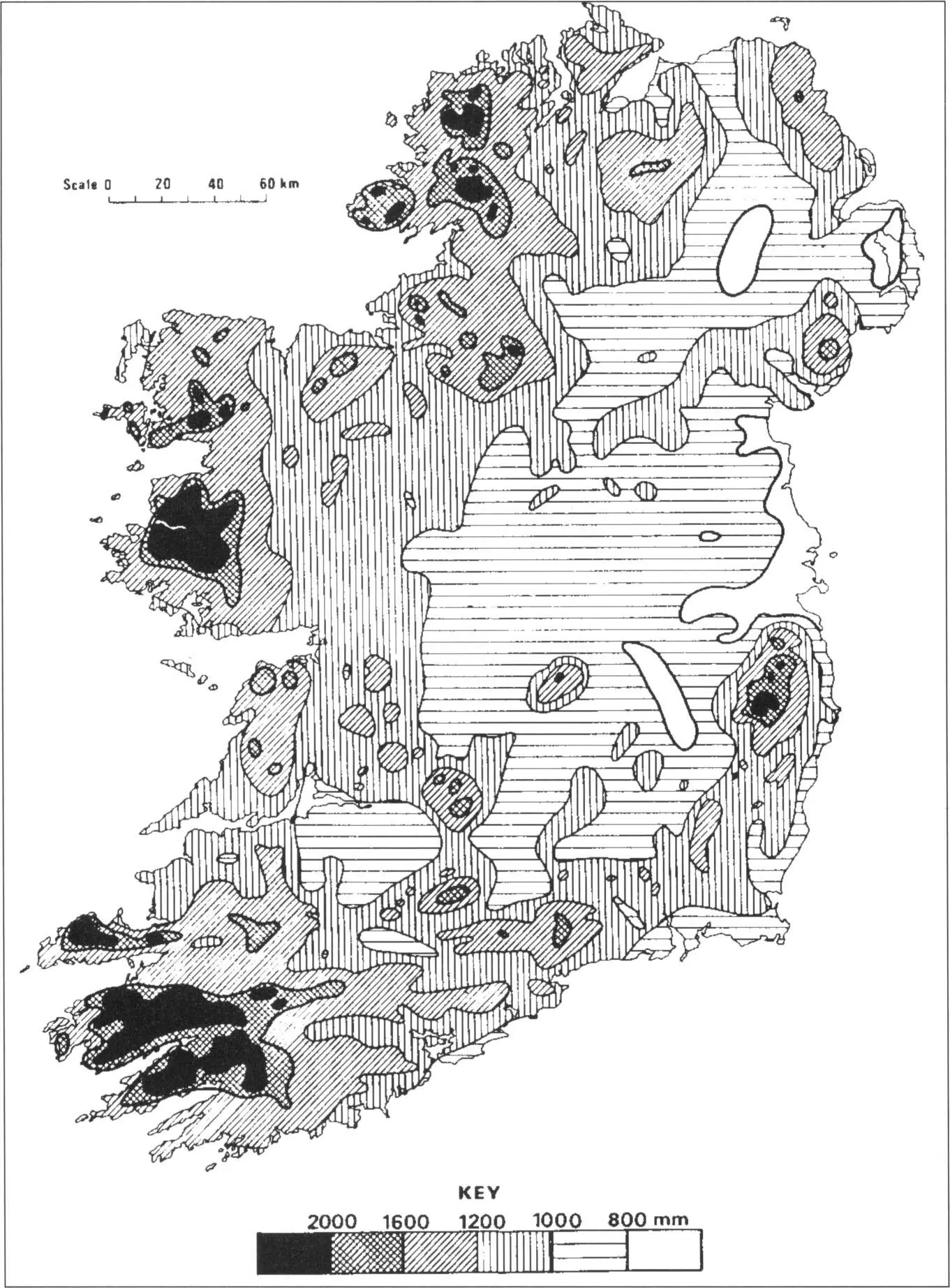

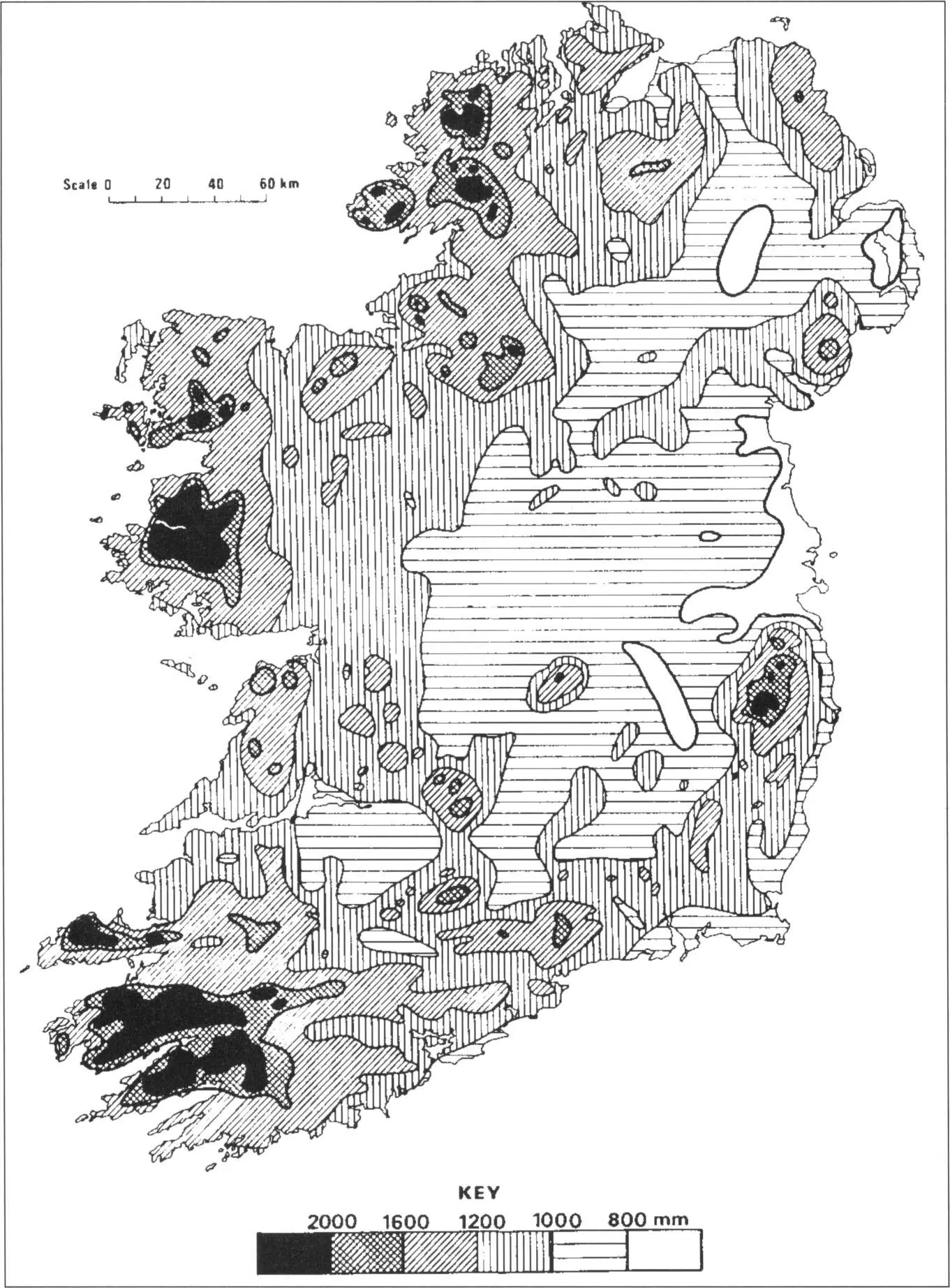

Levels of rainfall and humidity are much elevated on Irish mountains. The prevailing westerly winds are moisture-laden as they hit the west coast after travelling across several thousand kilometres of Atlantic Ocean, hence the often substantial and persistent falls of rain. Published figures from the highest recording station, set at 308 m at Ballaghbeama, Co. Kerry, show 396.5 cm of rain for the year 1960. At another station in Co. Kerry, at the Cummeragh River, 540 m above sea level, a total of 68.6 cm of rain was logged for just the month of December 1959, more than the average annual fall on the east coast. Further up the west coast at Kylemore, Co. Galway, close to sea level, the average over a 16 year period was 207.7 cm per year. At nearby Delphi, Co. Mayo, on the lee side of Mweelrea, rainfall of 254 cm per annum is not unusual, while in the wettest spots of Kerry and Galway precipitation can be as high as 250 cm per year. 3Such high rainfall encourages the development of boggy wet acidic soil and induces the leaching of nutrients. Still more important is the frequency of precipitation. The mountains of Donegal, Mayo–Galway and Kerry–Cork experience over 220 ‘wet days’ each year (a wet day is a period of 24 hours with precipitation of at least 1 mm).

Unfortunately no temperature readings are available from Irish mountains. However, for every 150 m rise in altitude the temperature decreases by approximately 1°C, so temperatures at any altitude may be estimated from isotherm maps corrected to sea level. For instance, at a height of 1,000 m the air will be at least 6.7°C colder than at sea level. The increased wind speed at the top of mountains will drop the temperature even further – a phenomenon known as the wind chill factor. Below freezing temperatures are encountered in winter as a thin white mantle covers the summits. On the country’s highest mountain, Carrauntoohil, snow can fall and lie for six months of the year, from November to early May 4, while on Mweelrea there may be snow around the summit for at least 20 days each winter.

Despite some extremes, the Irish climate is essentially mild, especially in the southwest. The mean daily air temperature recorded at Valentia Observatory, Co. Kerry, 1951–80 was 10.5°C, the highest figure from eight stations throughout Ireland. The coldest months were December (mean 7.7°C), January (6.6°C), February (6.5°C) and March (7.8°C). The mean annual number of days on which ground frost was recorded at Valentia Observatory 1960–84 (grass minimum temperature less than 0.0°C) was 38.6, approximately one third the number of days recorded at eight other stations throughout Ireland. 5

Wherever drainage is poor in the uplands or on the mountains, acid peat bog develops. This is one of the three main vegetation types typical of Irish high ground, the others being grassland and heath. On the exposed mountain summits, a more montane community is often present. Within the mountain environment there are many habitats hosting different groups of liverworts, mosses, ferns and flowering plants. Boulder screes, gullies, streams, vertical cliff faces, ridges and even snow fields that persist for several months each year provide specialist niches for the 58 species that are characteristic of Irish mountains and uplands.

Average annual rainfall 1951–1980. From Rohan 5.

The occurrence of calcareous outcrops, pockets of base-rich rocks such as mica schists, or out-flushings of mineral rich waters from deeper below, have dramatic impacts on the mountain flora, allowing many species to flourish profusely in an otherwise acidic environment. The largest limestone outcrop and mountain range in Ireland is Benbulbin, Co. Sligo. Benbulbin ascends vertically in the upper parts to a blanket bog-covered plateau with a maximum altitude of 526 m. On first sight this smothering of peat appears to defy ecological good manners, sitting on top of limestone rock which should, according to conventional rules, be supporting a community of calcicole or lime-loving plants. Peatland communities, made up of more astringent calcifuge or lime-fleeing species are normally found in lime poor habitats. The dramatic cliff walls, hanging over the lowlands below, are where most of Benbulbin’s renowned arctic-alpine flora is to be found.

Burning and grazing are traditional agricultural practices that have moulded and shaped the upland and mountain plant communities for centuries. However, since Ireland joined the European Union in 1973 the number of sheep grazing the mountains has increased dramatically, prompted by generous subsidies and premiums from Brussels and the government. Numbers nearly trebled from 3.3 million in 1980 to 8.9 million in June 1991. The heavy grazing intensity steadily eradicates the dwarf shrubs, such as heather and other ericales, and allows their replacement by grasses and, in dry places, bracken. Under high densities of animals, peat also suffers compaction which alters its oxygenation, leading to a premature death of the vegetation skin. The mechanical trampling leads to the disappearance of peat mosses, Sphagnum spp., whose water absorbency is crucial for the ecology of the bog. Tussock-forming sedges are the most resistant to the sheep’s aggression. The compaction of peat and the loss of Sphagnum , compounded by the removal of vegetation by incessant grazing, leads to a faster runoff of water down the mountain slopes. 6During a limited ecological survey in Co. Mayo, conducted nearly eight years ago, a total of 66 selected blanket bog sites were visited with the objective of identifying the more intact areas for conservation. Twenty-five, or 38%, of the sites, covering some 12,500 ha, contained significant areas that were overgrazed. Several sites among the 25 were completely destroyed. Indeed, it is estimated that in the case of very eroded blanket bog, rock-bare in places, it would take between 5,000 and 10,000 years for just 2.5 cm of soil to be regenerated. 6

Читать дальше