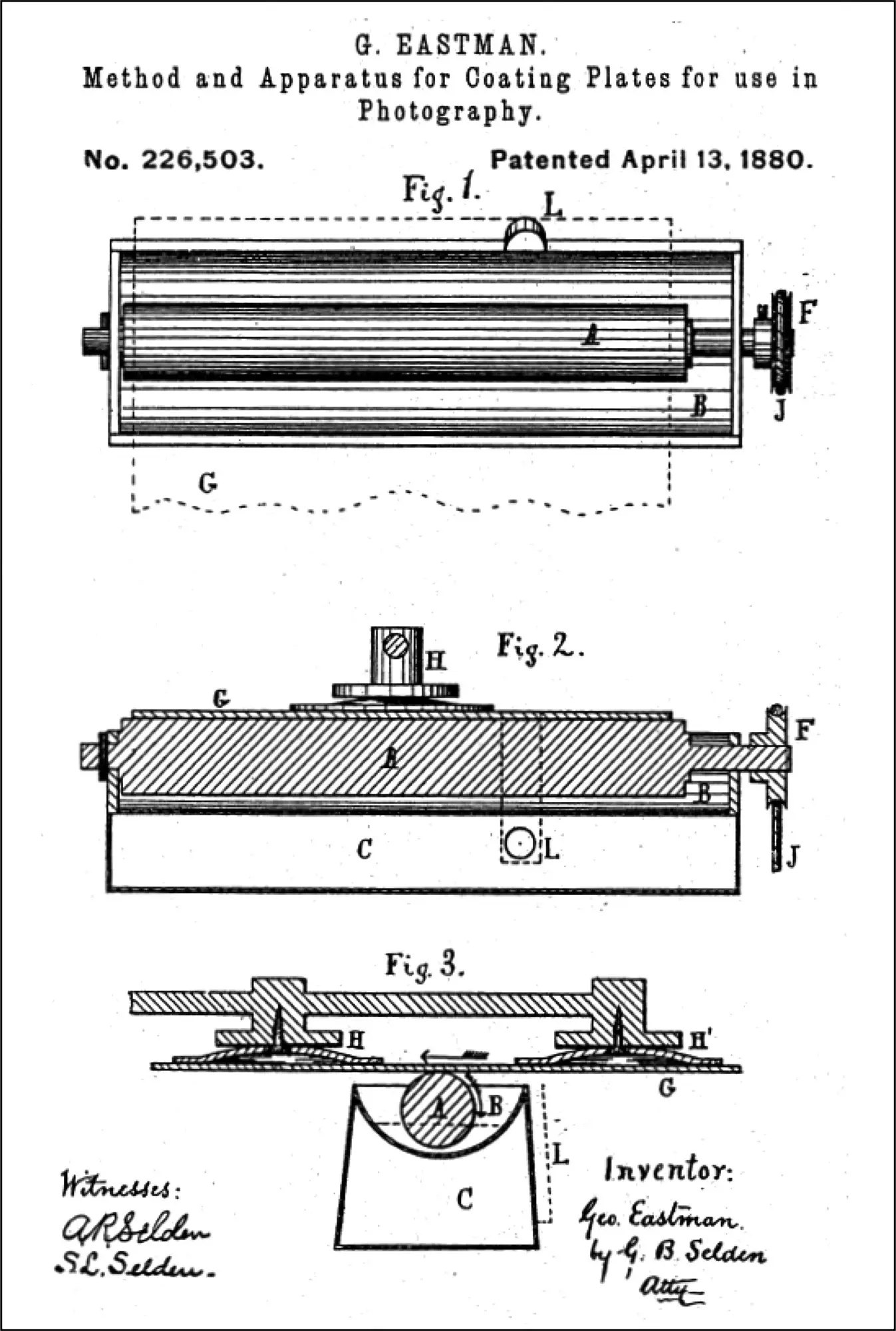

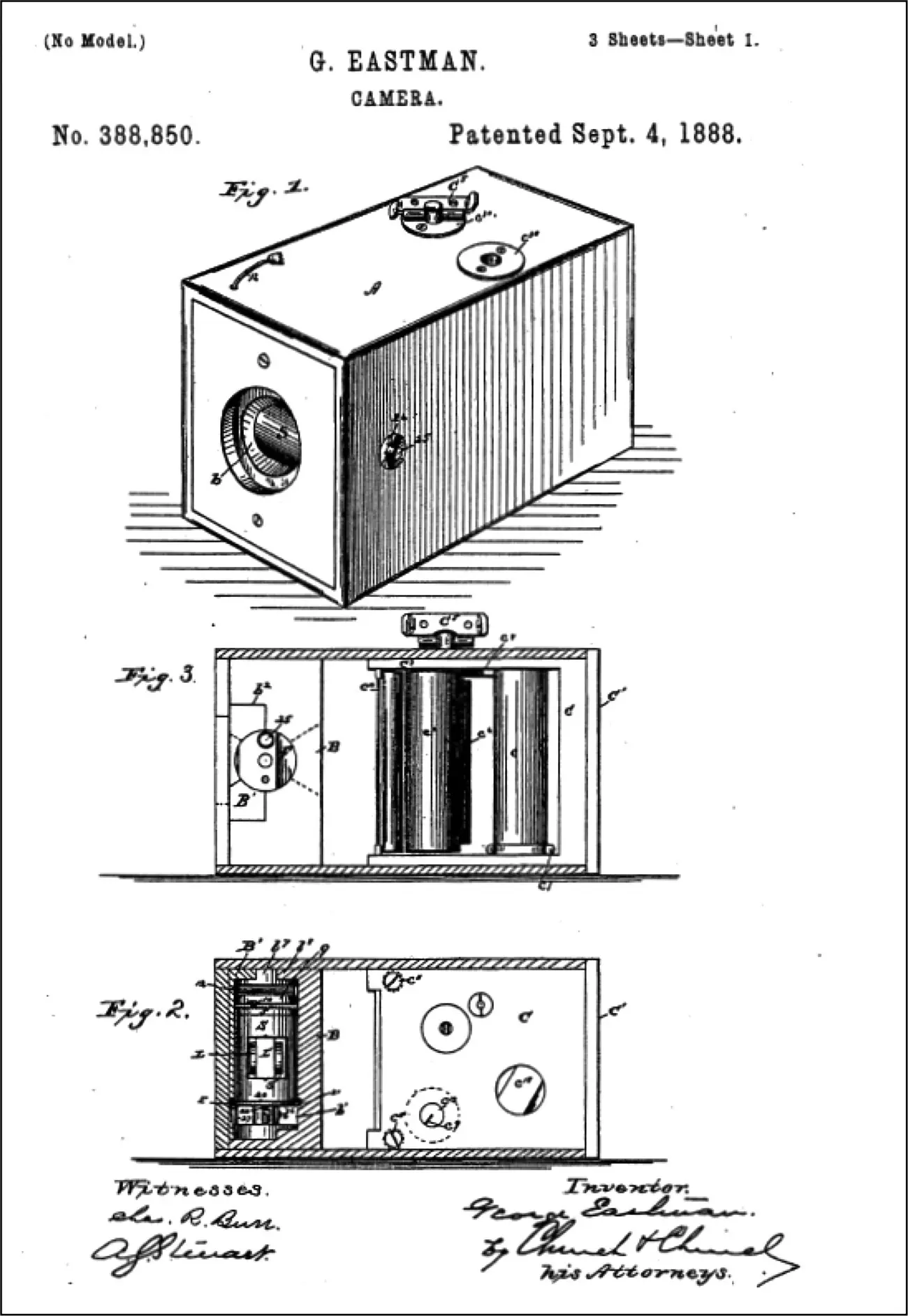

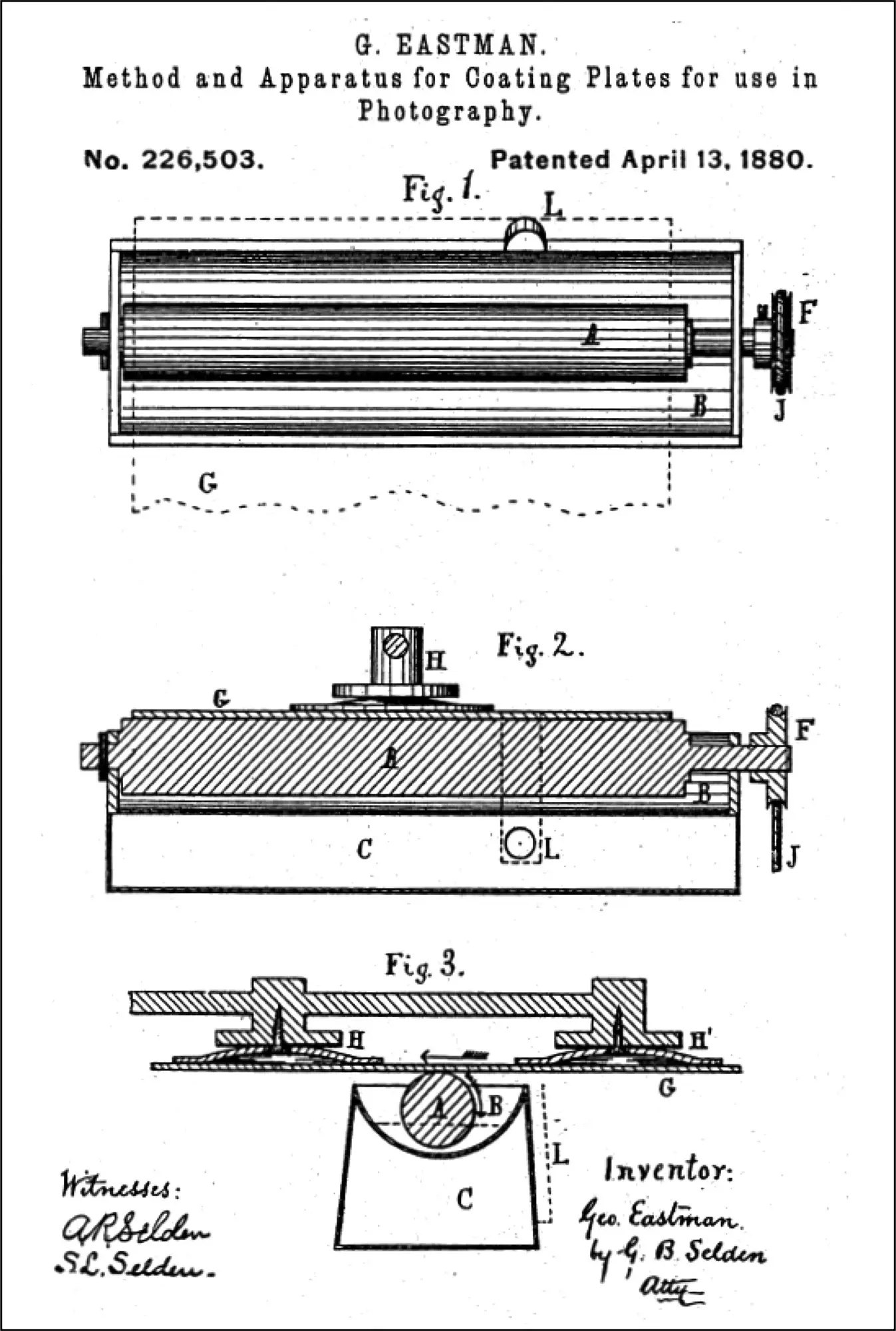

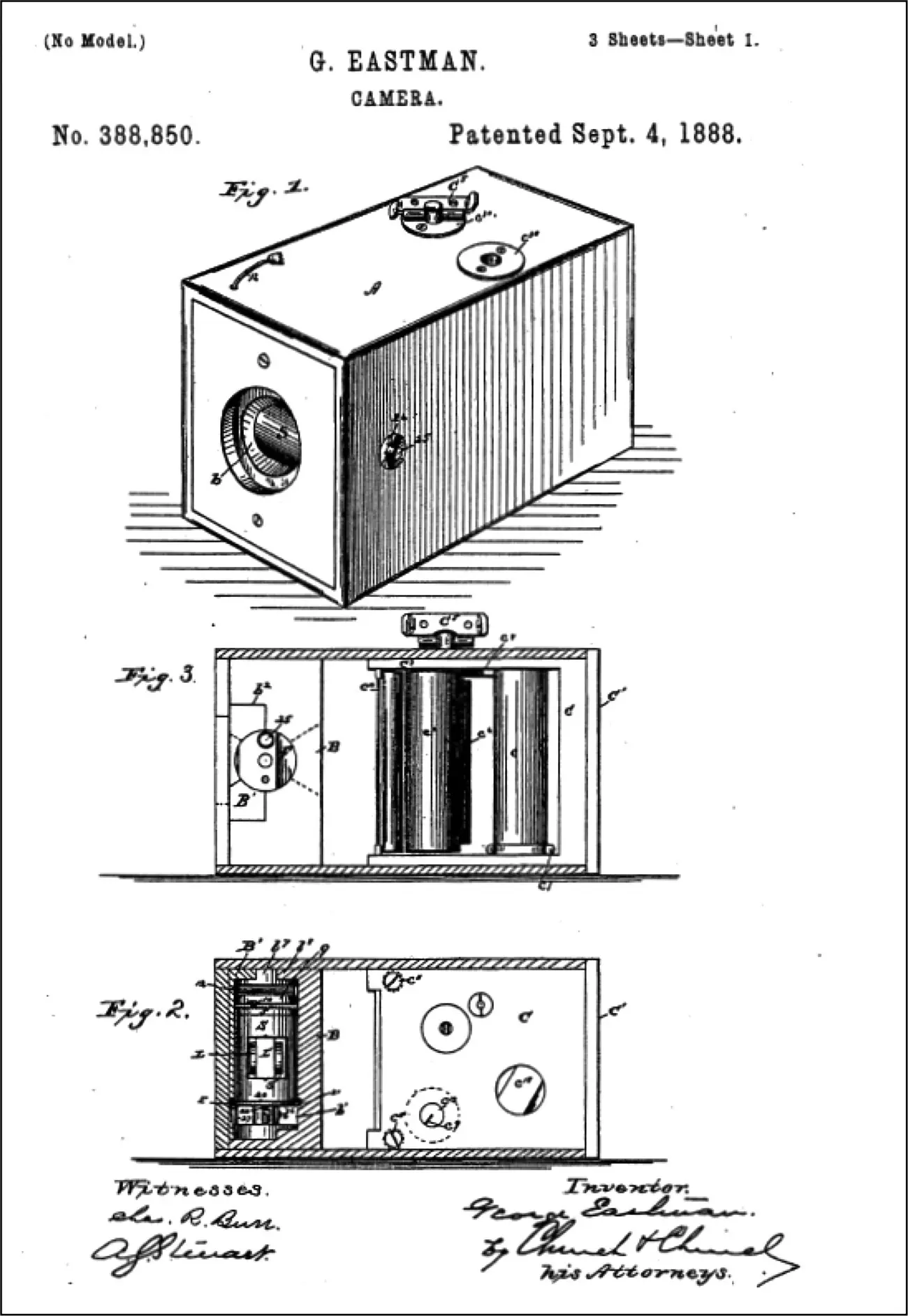

A year later, Eastman created flexible transparent film, which proved vital to the development of the motion picture industry. In 1892, he established the Eastman Kodak Company at Rochester, New York. In 1900, the Kodak Brownie became the first roll‐film, hand‐held camera.

George Eastman was also very generous with the fortune he earned, donating in excess of $75 million to a multitude of projects. He endowed the Eastman School of Music in 1918 and the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry in 1921. He also gave $20 million to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

On one day in 1924, George Eastman donated $30 million to the University of Rochester, M.I.T., Hampton Institute, and Tuskegee Institute. The latter two were schools for African‐American students, whose education was a particular concern of George Eastman.

Near the end of his life, Eastman became quite ill and became progressively disabled as a result of hardening of the cells in his lower spinal cord. He died at age 77 of his own hand on March 14, 1932.

INVENTORS AND INVENTIONS

Emile Berliner

DISC SOUND RECORDING

During the 1880s a contest developed between Thomas Edison and Volta Laboratory, a research laboratory founded by Alexander Graham Bell, where Bell's cousin, Chichester A. Bell, and Charles Sumner Tainter worked on improving the phonograph that Edison had developed in 1877. The contest was directed toward transforming Edison’s 1877 tin foil phonograph, or talking machine, into a device capable of taking its place alongside the typewriter as a business correspondence device. The contest involved, among other things, finding a substance to replace tin foil as a recording medium.

By the beginning of 1887, both sides in the contest announced the invention of a machine using a wax cylinder that would be incised vertically to match the sound vibrations. The same machine used to make the recording would be used for playback. Edison defined his wax cylinder apparatus a “phonograph.” C.A. Bell and Tainter named their apparatus a “graphophone.” Neither machine was much of a success. The phonograph did not succeed as a dictating device, so Edison’s company began to market pre‐recorded wax cylinders of popular music that could be played in the office or home, or even in coin slot machines in arcades, saloons‚ and elsewhere.

Tainter made improvements to the Volta graphophone, and his team also entered the entertainment field. Both sides of the contest had applied for a patent on the vertical cutting or incising of sound vibrations into a wax cylinder, and both sides made recordings on phonograph cylinders that could be played on the graphophone and phonograph.

Meanwhile, Emile Berliner in Washington D.C. began examining in detail both the phonograph and the graphophone to learn the advantages and disadvantages of each. He soon came to the conclusion that the wax recording cylinder was too soft and fragile to last as a permanent recording. A wax cylinder would wear out rapidly, so he sought a more durable substance. Also, the vertical cut, or hill and dale cut and grooves, were not deep enough to keep the stylus from skidding across the surface of the cylinder. The graphophone had the stylus attached to a feed screw that carried the stylus over the cylinder. A constantly deep groove enabled elimination of the feed screw, but something different from the vertical cut would be required. Soft wax cylinders could not be mass produced, so if recordings were to be widely distributed, another method of mass production of exact facsimiles was necessary.

Thus, there was a need for a different type of machine in the recording industry, one that did not use soft wax cylinders, one that did not use vertical cut grooves that were alternately deep with loud sounds and shallow with soft sounds, and one that employed a relatively hard and permanent recording medium that could be easily reproduced in large quantities. Both the Edison and Tainter teams eventually overcame many of the cylinder’s defects; however, the cylinder record appeared already doomed to extinction by the flat disc record.

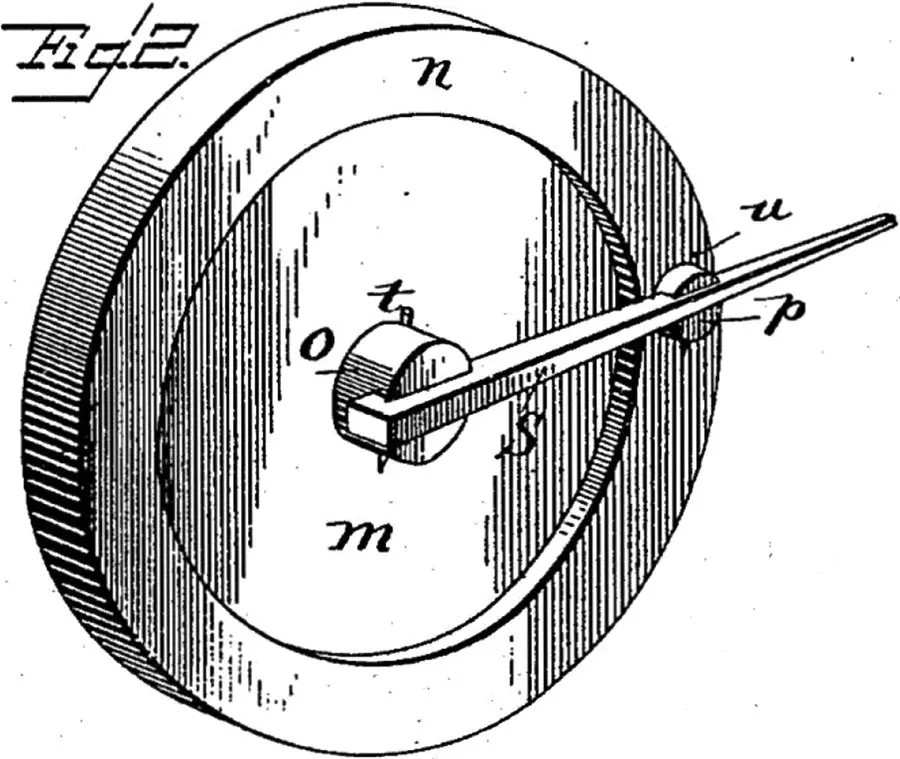

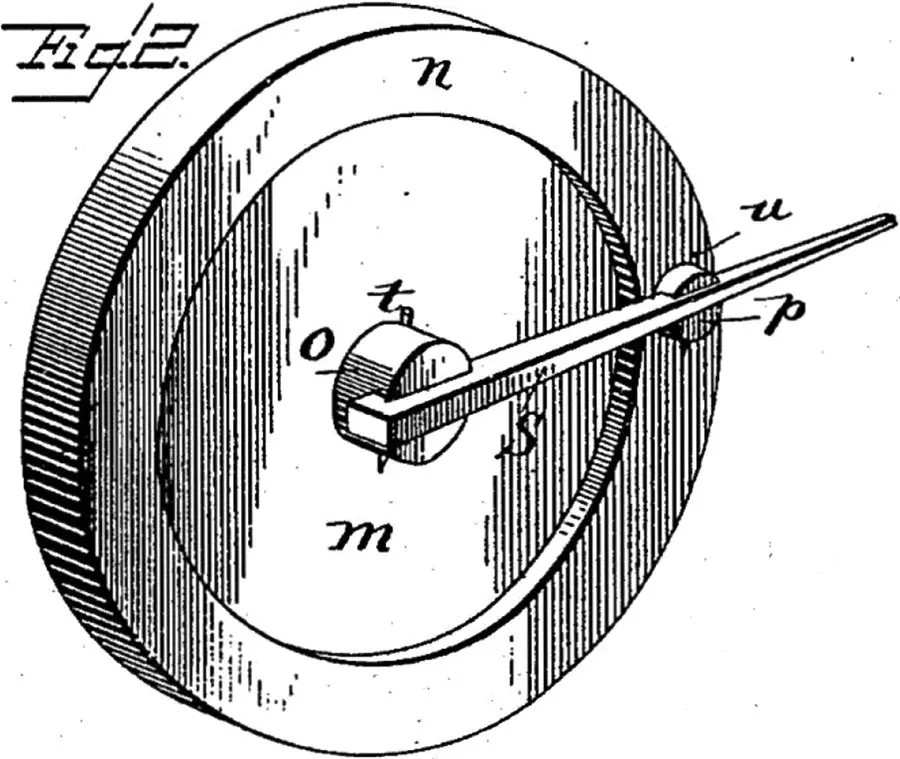

Emile Berliner went through many trials and errors in developing what he called the “gramophone.” Early in his work, Berliner decided upon the disc format using the lateral vibration developed by Leon Scott in Scott's phonautograph. Scott had developed his machine in the 1850s for the sole purpose of visually recording vibrations of the voice so they could be studied by those involved in analyzing human speech. Scott's vibrations were made by speaking into the large end of a megaphone whose small end included a thin diaphragm that could freely vibrate. A thin brush attached to the diaphragm would make tiny tracks on blackened glass. These lateral vibrations could then be photographed and studied. Apparently, it never occurred to Scott or anyone else at the time that if these tiny tracks could be fixed, and the stylus passed through the tracks, the reverse process would take place and sounds would be reproduced through the large end of the megaphone.

Starting with Scott's phonautograph, Berliner first tried to replicate the thin tracing Scott made on blackened glass on a sturdier substance through a photoengraving process. Berliner was unaware that this was a practice that had been previously advanced by a Frenchman, Charles Cros, in a paper written in April 1877 and deposited with the French Academy. In this paper, Cros for the very first time, stated a theory for recording and reproducing sound. However, Cros never acted upon his theory. Had he done so, he would have been the inventor of the talking machine and not Thomas Edison. Edison was never aware of Cros or his paper, and Edison’s tin foil machine owed nothing to Cros’ theory. Meanwhile, Berliner found that trying to photoengrave the surface of a glass disc led to problems, so he then turned to an etching process.

After attempting many different substances, Berliner turned to zinc. After many failed attempts, he developed a process for coating a zinc disc made from regular stone maker's zinc, with a beeswax and cold gasoline mixture. The coating was then cleared away with fine lines made by a stylus attached to a mica diaphragm so that it would vibrate. After coating the blank reverse side of the disc with varnish, the disc was immersed in an acid bath. After a certain time, the acid etched the fine lines into grooves on the zinc, leaving the remaining parts of the disc untouched. With the vibrations fixed into the zinc, the disc was able to be placed on a turntable, and the sound reproduced with a steel stylus.

Early disc records were made using this process. Berliner’s method, however, required two machines, one for each process. As a name for the whole operation, the inventor coined the word “gramophone.” His earlier patents on this device were No. 372,786 dated November 8, 1887, and No. 382,790 dated May 15, 1888. Berliner then faced the problem of finding a process to reproduce the master zinc record. First, the master had to be electroplated resulting in a metal reverse, or negative record, with grooves projecting outward instead of inward. The negative could then be used to stamp positive copies of a substance that would hold the impression exactly.

Читать дальше