In November 1887, Edison moved his research and development team to a new facility in West Orange, New Jersey. He began working on the phonograph, which project he had set aside when developing the electric light bulb in the late 1870s. By 1890, Edison was manufacturing phonographs for both home and business. He also developed the entire system to make the phonograph work, including the records, equipment to record sound on the records, and equipment to manufacture both the records and the phonographs. Edison used cylindrical paraffin records to produce sound, but in later years the circular recording disk was developed, putting Edison out of the record business. Regarding movies, Edison also developed the complete system needed to both make movies and to show motion pictures, and in 1913 introduced the first talking movies. By 1918, the motion picture industry, which he was instrumental in creating, became so competitive that Edison got out of this business altogether.

On June 8, 1903, Thomas Alva Edison signed an agreement with his son, Thomas A. Edison, Jr., whereby Edison’s son agreed not to use his own name in a business enterprise in exchange for a weekly allowance of $35.

One of the commentators relied upon during my research noted that the public, in the latter part of the 19th century, looked upon the developments of scientific technology as a source of hope, not with distrust. This commentator felt that the positive public attitude garnered toward the power of science and technology as a result of Edison’s work, among others, is one of the most important legacies to emanate from the technological developments of that era.

In 1884, Edison’s first wife Mary passed away, leaving him with three small children. He married Mina Miller in 1886. Thomas Alva Edison died in West Orange, New Jersey, on October 18, 1931. Today, he has truly attained folk hero status thanks to his inventions.

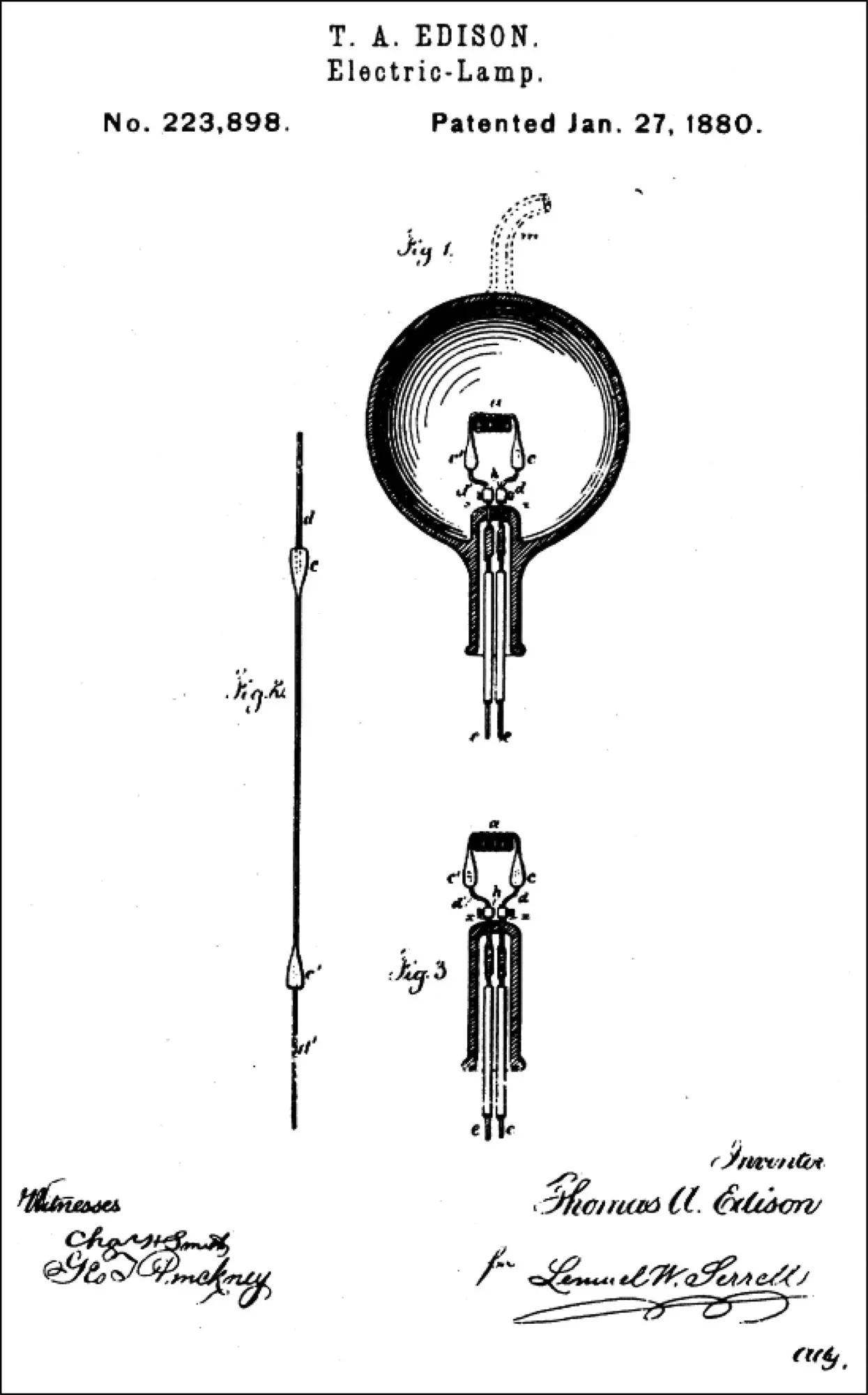

9 The Patent Application

9.1 INTRODUCTION

This chapter discusses the information that goes into a properly prepared patent application, enabling you to adequately review an application covering your invention when it is presented for your review and comments prior to filing the application. One of the important aspects of the Patent Law is that an inventor should carefully review his or her patent application for correctness and completeness before it is filed with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. This chapter also briefly summarizes the history of patent application content leading to the present system and its requirements for a properly filed application. Also discussed are the goals intended to be met in the preparation of a properly prepared application, the use of provisional patent applications, and how to conduct a rigid review of a patent application covering your invention.

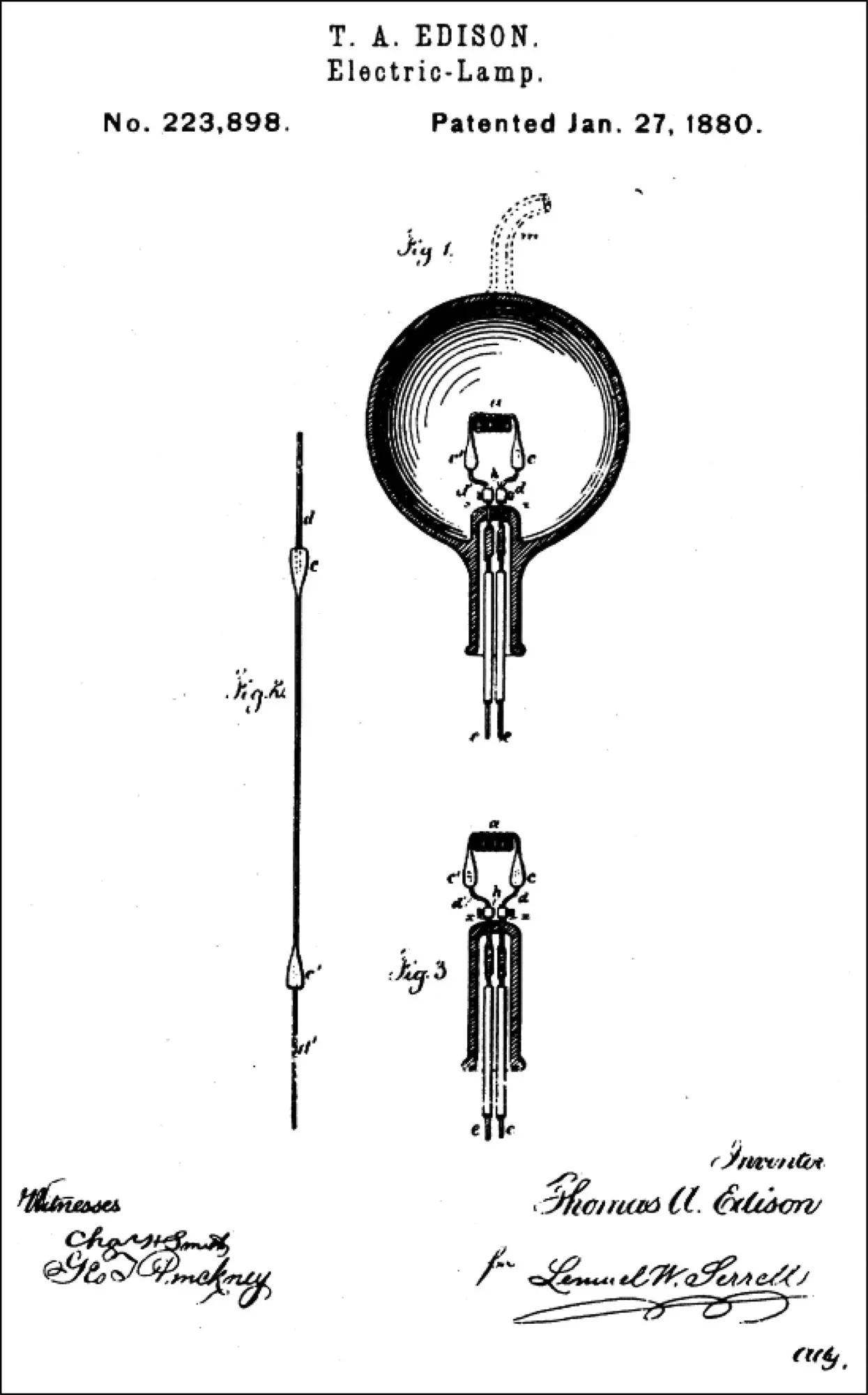

9.2 REGISTRATION SYSTEM EVOLVING INTO AN EXAMINATION SYSTEM

You will recall from earlier chapters that from the year 1793 until 1836, there was no patent examination system in the United States, and inventors were merely required to furnish the government with a description of their invention, and the government would then register that explanation. This procedure caused immense difficulty when infringers were brought to court, and the court had the burden of determining just what the inventor was claiming as his or her invention, without any direct statement in the registration certificate that defined the novel point or points of the invention. Thus, the courts had no knowledge of the prior art against which the novelty of the “invention” could be measured.

This system changed in 1836, owing to the efforts primarily of Senator John Ruggles of Maine. Congress created a Patent Office and an examination system, and inventors were required not only to describe their invention in their applications for a patent, they had to specifically set forth what it was they were urging as novel over the prior art. The requirements of the system today are basically the same as established in 1836, even as the level of technology has increased approximately one hundred fold. One of my favorite tests to measure advances in technology between 1836 and the present is to determine how fast a human being could possibly travel in 1836 using any means possible, for example, a horse, and how fast a human being can travel today using any means possible, for example, an orbiting space shuttle. The answer may stagger your imagination.

9.3 GOAL OF A PROPERLY PREPARED PATENT APPLICATION

On the basis of historical development, the patent application today must clearly and completely include a specification that sets forth a complete and proper description of the invention, and claims that specifically define the scope of patent protection sought by the inventor. The patent application also must result in an issued patent that will advise and inform the public of the strict definitions of the metes and bounds of the technology protection you have obtained from the government. Competitors must be able to easily ascertain what they can produce and what they cannot produce in view of the patent fence that has been erected through your patent. The patent application specification must also describe each important detail of the structure and at least one cycle of operation of your invention. The claims must also define your invention beyond the state of the prior art. Your patent is ultimately a technical paper advising posterity of the advance in technology embodied in your invention. Remember, the history of the patent laws stresses that the 20‐year exclusive position in your invention is granted as consideration for the full and complete disclosure of your invention to the public for use after your patent rights expire.

In my law school course, where I teach students on track to become patent attorneys, I begin my lecture on patent application preparation by indicating that the application is basically a sales document, where you are selling the concept to the Patent Examiner that the application defines an invention, without question, and that the only issue for examination is to ensure that the invention has been adequately defined over the prior art in the claims.

The patent application itself, in general terms, consists initially of a statement of the field or art to which the invention pertains. This is followed by setting forth the problem which the invention is directed toward solving and a statement of how others have attempted to solve the same problem and failed. This is followed by stating that your invention will achieve certain advantages and results that are not achieved by the technology shown in the prior art, and this is followed by a statement, in summary form, of the specific structure, elements‚ and/or function of your invention which provide these advantages, objectives‚ and results.

Following the above in a patent application is a brief description of the various drawing views, where applicable, followed by a complete description of the invention, which sets forth in concise detail a description of the complete interrelated structure of the invention, referring only to important elements of the invention, followed by a description of at least one cycle of operation. This is followed by the all‐important claims, which will be discussed separately in Chapter 10.

The above general “outline” for a patent application usually varies among some patent attorneys. For example, some patent applications are drafted without reference to advantages, results‚ or objectives. Whatever preparation technique was used to prepare your application, satisfy yourself upon your review that all aspects of your invention are clearly covered in the patent application.

Читать дальше