Several large rivers flow through arid landscapes but manage to sustain their flow because of the high discharge arriving from the upper non-arid parts of their drainage basins. The Indus, for example, maintains its long lower course through the arid area of Pakistan by seasonal discharge from snowmelt and orographic monsoon rain that falls in the mountains of its upper course. Other large rivers with a significant part of their drainage basins arid include the Nile, Colorado, Niger, and Murray-Darling. Commonly, water in these rivers is utilised by construction of dams and reservoirs, and as such requires careful management ( Chapter 9).

The 6500 km long Nile is a well-known example. It rises as the White Nile in wet Central Africa from Lake Victoria and flows north for about 2700 km through the Sahara Desert without any significant water input. On the other hand, a high rate of evapotranspiration occurs in the wetlands of the Sudd. The annual rainfall decreases from near 2000 mm in the Lake Victoria area to about 175 mm at Khartoum. The White Nile is joined at Khartoum by the Blue Nile and further downstream by the Atbara. Both streams are seasonal and monsoon-fed from the mountains of Ethiopia. About 85% of the annual flow of the Blue Nile is concentrated between July and October. The Atbara is even more seasonal (Woodward et al. 2007). A seasonally flood prone Nile then flows through Egypt to build a fertile delta.

Milliman and Farnsworth (2011) estimated that the rivers of the world altogether discharge about 36 000 km 3of water to the oceans annually. Given the pattern of global precipitation, rivers of northern South America and South, Southeast and East Asia contribute about half of this amount. Table 1.1shows that large rivers of these regions provide most of this discharge. The discharge of the Amazon is particularly high, being 6300 km 3per year, a figure comparable with the total annual discharge of the next eight large rivers.

3.5 Sediment in Large Rivers

Meade (2007) described large rivers as massive conveyance systems for moving clastic sediment and dissolved matter over transcontinental distances. To illustrate, the Amazon and Orinoco are large rivers that transfer sediment for thousands of kilometres from the active margin of South America to its passive edge – from the Andes and its forelands in the west to the low floodplains and deltas of the two rivers on the east coast. The sediment is transferred between the source and the sink in steps, being alternatively transferred down-channel and stored in the valley for years in extensive alluvial plains, huge floodplains, or channel bars.

The mountains and forelands of the Andes are essentially the sources of the sediment of these rivers and such sediment is recycled as it travels in the downstream direction. The source of virtually all the modern sediments in the rivers is the Andes itself. The tributaries of the Amazon which do not originate in the Andes or its foothills, contribute very little sediment to the Amazon. This may also be true for other large rivers that originate in young fold mountains. In their study of global sediment, Milliman and Syvitiski have associated sediment sources with high mountains and stated ‘probably the entire tectonic milieu of fractured and brecciated rocks, oversteepened slopes, seismic, and volcanic activity, rather than simple elevation/relief …. promotes the large sediment yields from active orogenic belts.’ (Milliman and Syvitiski 1992, p. 540). Meade (2007) discussed ( Figure 3.1) the example of the Orinoco River which collects water discharge from most of the basin irrespective of geology, but sediment only from the Andes and Llanos. Figure 3.1also illustrates the progressive increase in discharges of water and suspended sediment downstream.

Examples of downstream sediment transfer are common. The Rio Madeira deposits a considerable amount of sediment as it emerges from the Andes Mountains to the lowlands of the Amazon. Some of this sediment is stored in the river but eventually moves downstream (Guyot et al. 1996; Dunne et al. 1998). About half of the sediment eroded from the Andes is deposited in the Andean foreland (Aalto et al. 2006) before removal. Before the Three Gorges Dam was closed, the Changjiang used to deposit nearly 100 million tonnes of sediment annually on floodplains and in lakes and stream channels between Yichang and Datong (Xu et al. 2007). The sediment was likely to have been derived from upstream mountains.

As the sediment emerges from the highlands, individual grains are as likely to be stored in the valleys of many large rivers as to travel downstream. When stored, they may remain at rest for a sufficiently long enough time to decompose in situ to a partly dissolved state which is removed by the river as solution load. The rest of the sediment remains in the solid state in the channel and is transferred downstream during high flows of the river as suspended load, or even as bed load if the grains are still big and the flow is powerful enough. Moving downstream via alternate storage and transfer, the sediment becomes mature in composition and over time may consist of more than 90% quartz, having lost rock fragments and feldspar by abrasion and decomposition. Of its maximum annual channel sediment load of about 1200 million tonnes at Óbidos, virtually all the suspended sediment of the Amazon comes from the Andes either via the main stem Amazon or one of its major tributaries, the Madeira, the headwaters of both starting deep in the Andes. The floods may take the sediment-laden water across the floodplain, deposit the sediment on the floodplain, and then during the falling-water season, return the clear water to the channel. The floodplain of the Amazon within Brazil measures about 90 000 km 2. The floodplains slowly grow vertically in floods and lose area by bank erosion associated with channel movement. These floodplains of Brazil ( várzea ) form a special environment with typical vegetation and animal life, strongly related to flood pulses. Junk et al. provide a detailed account of the physical and ecological characteristics of these floodplains in Chapter 5.

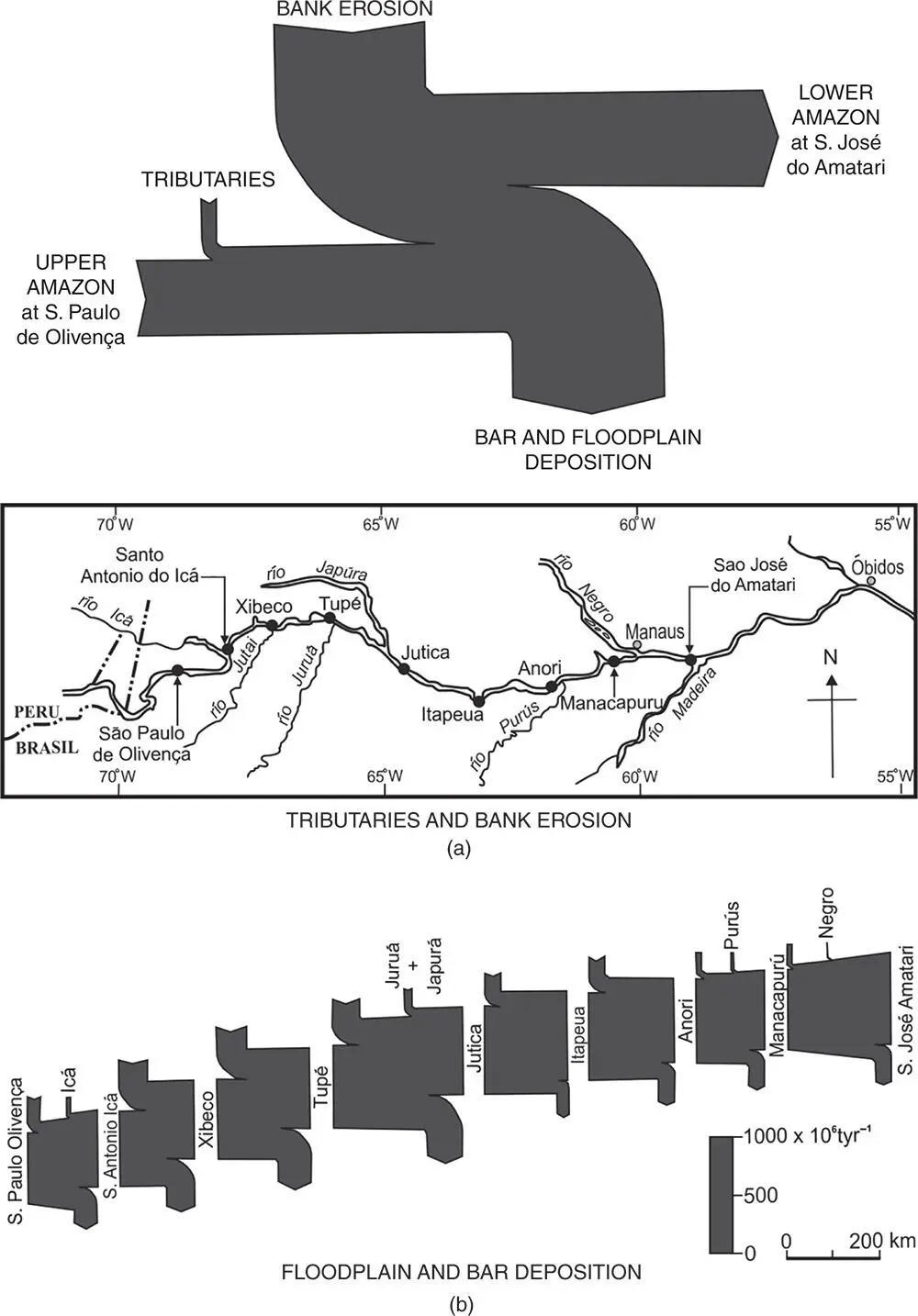

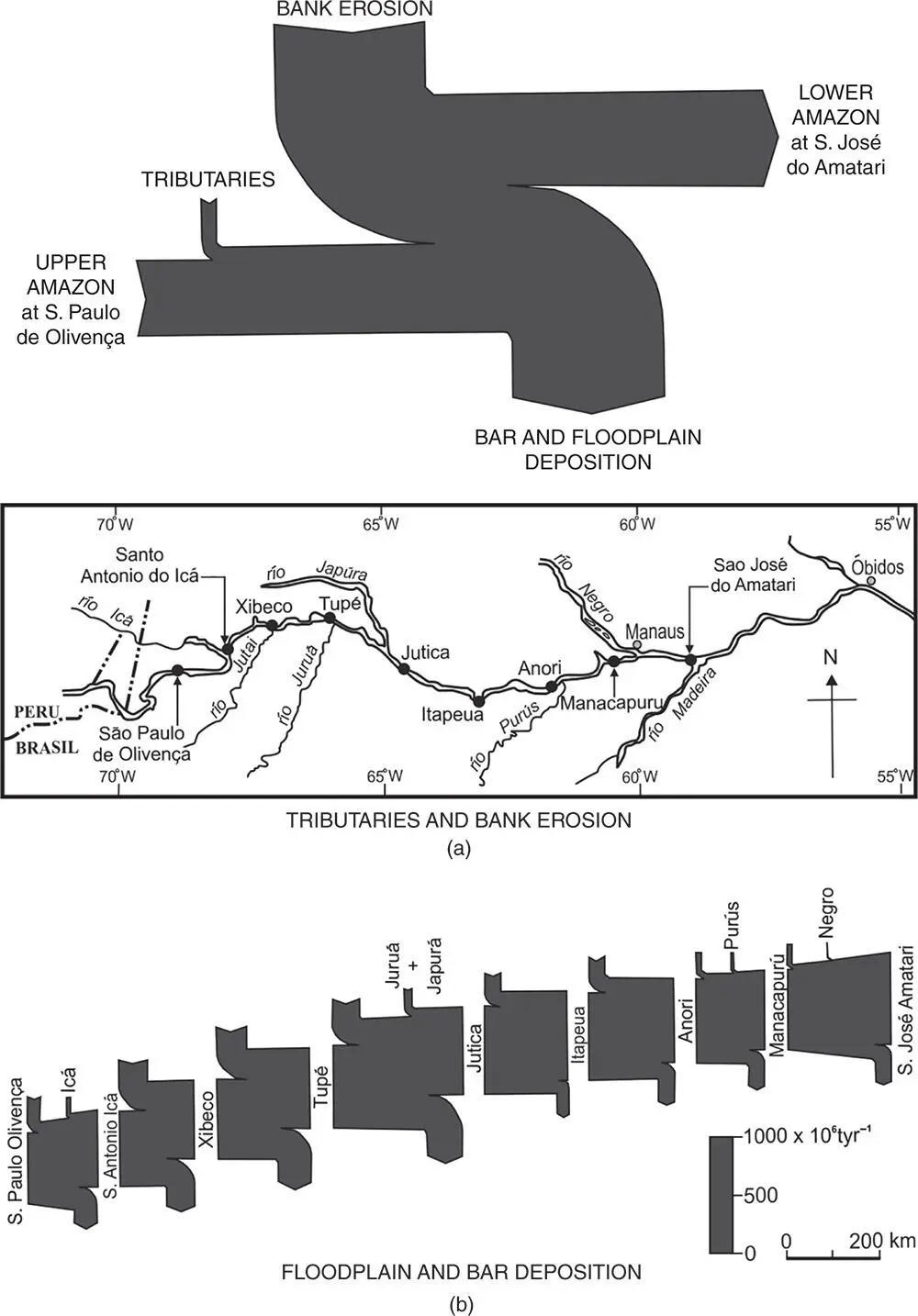

It is not uncommon for large rivers to transfer sediment both as downward flux and also sideways for floodplain-building (Goodbred and Kuehl 1998; Dietrich et al. 1999; Galy and France-Lanord 2001). The volume, however, is enormous for the Amazon River ( Figure 3.3). If we consider the entire Amazon, more sediment moves laterally in and out of floodplains than as downstream flux (Meade 2007). Residence time for such sediment between the confluences of the Amazon with the Jutai and Madera has been estimated to be in the range of 1000–2000 years (Mertes et al. 1996). It could be longer, and thus sufficient time to change the proportion of sediment to nearly all quartz grains.

The lowermost gauging station on the Amazon is at Óbidos, about 1000 km above the sea. It is difficult to measure sediment deposition further downstream but apparently much sediment is deposited on floodplains and in partly filled floodplain lakes. Plumes of sediment are seen in satellite images entering the Atlantic from the Amazon mouth ( Figure 3.4). Part of that sediment that passes through the sediment mouth settles on the ocean floor but the rest travels northeast along the coast to reach the Orinoco Delta. The outer Orinoco Delta includes more sediment from the Amazon than from the Orinoco. The Amazon probably provides the best example of large-scale sediment transfer but similar processes of sediment transfer and storage occur in other large rivers too.

Figure 3.3 Diagram showing average annual sediment movement between channels and floodplains of a 1500 km segment of the Amazon. (a) Schematic generalisation of average values for the entire 1500 km reach and map. (b) Individual sediment budgets for eight consecutive reaches of the main river between São Paulo de Olivença and São José do Amatari.

Читать дальше