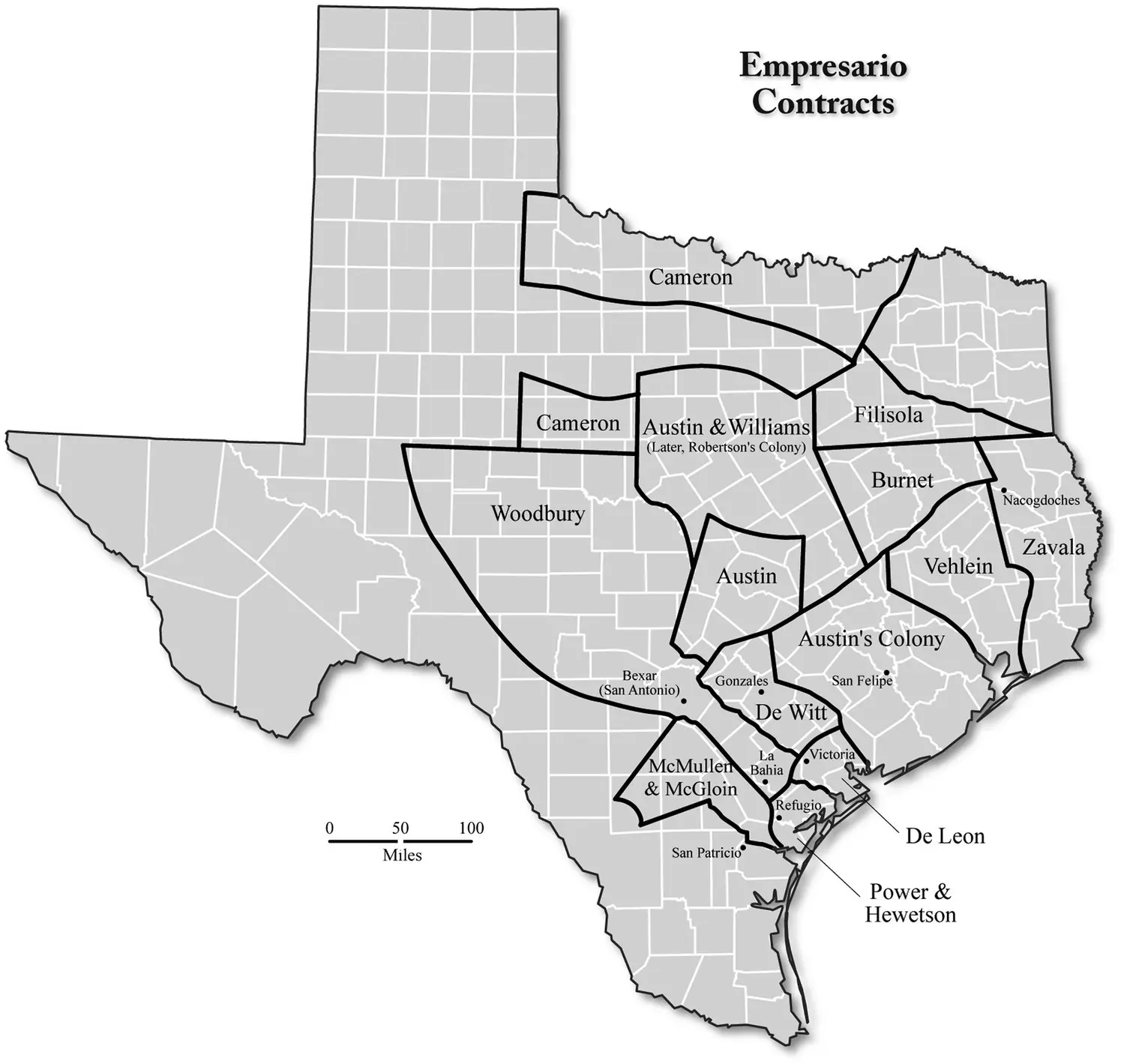

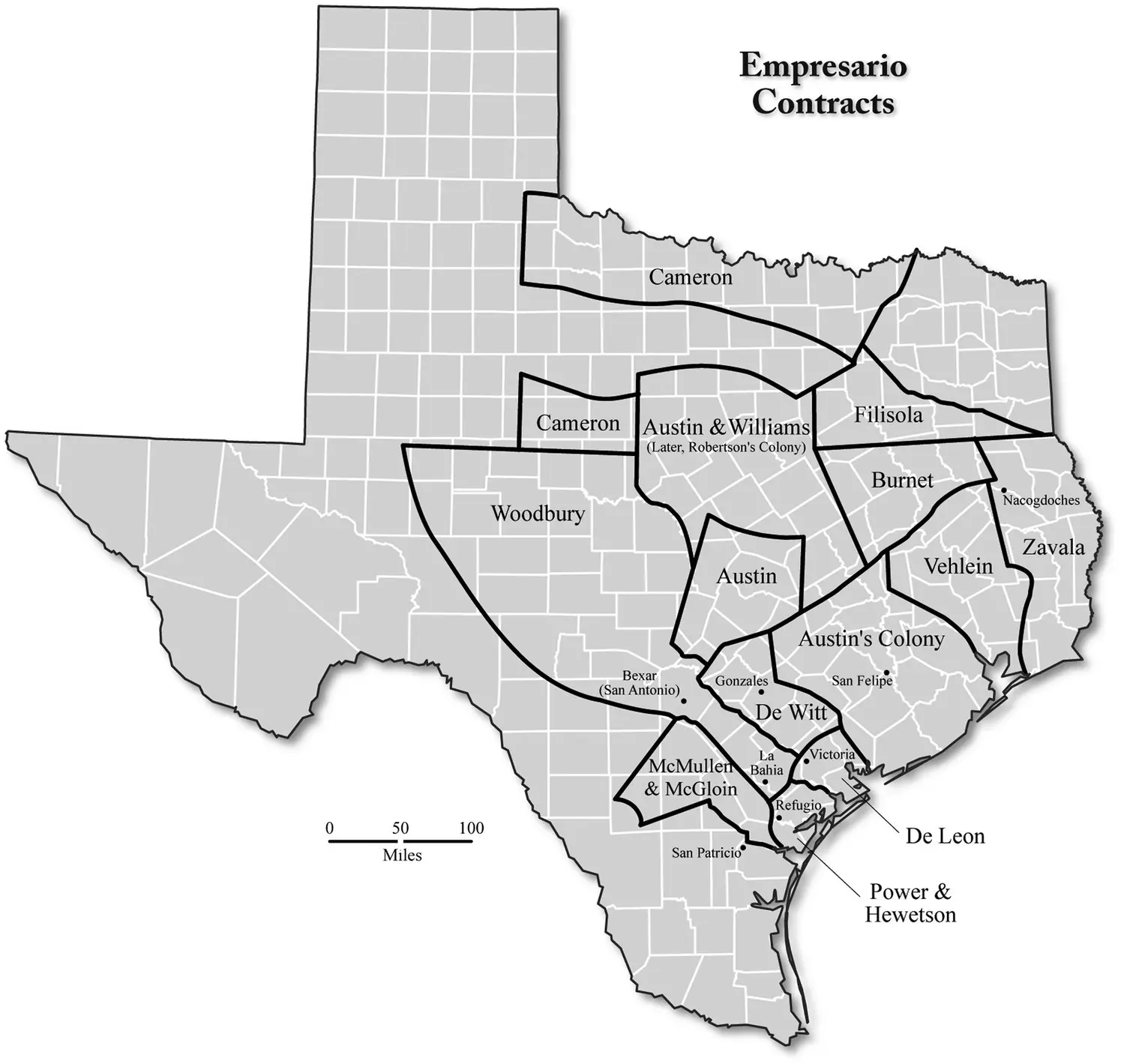

To the west of Austin’s original lands, between the Guadalupe and Lavaca rivers, Green DeWitt planted a colony with its center at Gonzales. This contract expired in 1831, however, by which time DeWitt had settled only about one‐third of the 400 families he had pledged to bring. Bordering the DeWitt colony to the southeast lay the tract belonging to the rancher Martín de León. Issued at San Antonio in 1824 (even before the enactment of the Colonization Law of 1825), this grant had ill‐defined boundaries, which caused some disputes between de León’s and DeWitt’s settlers, at least until DeWitt’s land became part of the public domain in 1832. De León’s colony, with its principal settlement at Victoria, remained small, though titles had been issued to 162 families by 1835. Figure 3.2shows the extent of the empresario contracts in the region.

Most other empresarial colonies achieved only moderate success in the 1820s. In 1825, Robert Leftwich received (on behalf of a cooperative venture called the Texas Association of Nashville, Tennessee) a contract to settle lands situated northwest of Austin’s lands, but no one colonized them until the early 1830s, when a Tennessean named Sterling C. Robertson took over as empresario for the Texas Association. Farther east, Haden Edwards’s colonization contract called for 800 families to settle around the Nacogdoches region, but following his armed uprising in 1826 against government officials (the so‐called Fredonian Rebellion, discussed later) his vacated land reverted to the state. Part of Edwards’s tract went to David G. Burnet, and another portion of it went to a German merchant named Joseph Vehlein in 1826. Lorenzo de Zavala, one of the framers of the Mexican Constitution of 1824, received land along the Sabine River in 1829, but he never colonized it.

Figure 3.2 Empresario contracts.

The Native Mexicans of Texas

As Anglo settlers arrived in East Texas, the native Mexicans were, according to historian Andrés A. Tijerina, experiencing a resurrection in fortunes following the devastation of the war for independence. Ranches between Béxar and La Bahía (the latter called Goliad after 1829–from an anagram of the name Hidalgo) were reestablished in the mid‐1820s along the entire stretch and on both sides of the San Antonio River and its tributaries. These ranches belonged to Texas Mexicans of wealth and status, men like Martín de León of Victoria, Erasmo and Juan N. Seguín of Béxar, and Carlos de la Garza of Goliad. In Nacogdoches, a few brave souls had held the town together throughout the upheaval of the 1810s, and by 1823 a steady flow of the Mexican population into Nacogdoches and the surrounding district was apparent. In the 1830s, Nacogdoches consisted of a small town surrounded by approximately fifty founding ranchos. In South Texas, the Trans‐Nueces ranching frontier spread northward from the Rio Grande in the 1820s to cover the present counties of Willacy, Kenedy, Brooks, Jim Hogg, Duval, Jim Wells, and Kleberg, with its northern point at Nueces County. Ten years later, approximately 350 rancherías (small family‐operated concerns) existed in this region, many of which provided the foundations for future Texas towns.

Anglos and the Mexican Government

Anglos, whether they had entered Texas legally or illegally (most of those fleeing debts or the law in the United States arrived in Texas independently rather than under the guidance of an empresario), began to worry the Mexican government. For one thing, many of the Anglos were not taking their Mexican nationality seriously. Although some of the Anglo newcomers had built homes in the predominately Tejano settlements and ranchos of San Antonio and Goliad, most preferred living a good distance away from Comanche hunting grounds, in the hope of avoiding Indian attacks. Concentrated in the eastern sections of Texas, they lived a semiautonomous life, conducting their affairs in ways that made the Mexican government uneasy: squatting on unoccupied lands; engaging in forbidden transactions with commercial establishments in New Orleans; applying American practices to local situations; speculating with their properties; working slaves in the cotton lands around the Brazos and Colorado Rivers; and otherwise disregarding the conditions (and oath) under which they had been allowed to settle. Their decidedly independent attitude manifested itself at Nacogdoches as early as 1826, when the empresario Haden Edwards proclaimed the independence of the region, his so‐called Fredonian Republic. For months, disputes had developed between the old settlers in Nacogdoches and Edwards’s colonists over land titles; a break from Mexico, thought Benjamin Edwards (Haden’s brother and the actual leader of the insurrection), would resolve the conflict in favor of the newcomers. But the armed revolt collapsed when more successful, foreign‐born colonists denounced the affair and Austin led his colony’s militia, along with Mexican officials, to Nacogdoches to suppress it. Nonetheless, the episode heightened concerns in Mexico that further American immigration might dissolve Mexico’s hold on Texas. Meanwhile, in Texas, immigrants became distrustful of a government that had just voided an empresario contract without due process of law.

In order to evaluate how the national government might best deal with the troubles in Texas, Mexican officials dispatched Manuel de Mier y Terán, a high‐ranking military officer and trained engineer, to the north. Crossing into Texas in 1828, Mier y Terán reported that the province was flooded with Anglo Americans, that Nacogdoches had essentially become an American town, that prospects for assimilation of the Anglos into Mexican culture appeared dim, and that the Anglo settlements generally resisted obeying the colonization laws. Once back in Mexico, his concerns over American immigrant loyalty mounted, and his fear that Mexico might indeed lose Texas to the newcomers intensified. Mier y Terán’s recommendations spurred the drafting and implementation of the new law of April 6, 1830.

The Law of April 6, 1830, intended to stop further immigration into Texas from the United States by declaring uncompleted empresario agreements as void, although Mier y Terán let stand as valid those contracts belonging to men who had already brought in one hundred families. Thus, Americans could still immigrate to Texas legally but only into the colonies of Austin or DeWitt: the only two empresario grants that met the general’s requirement, neither of which was filled to capacity. Furthermore, future American immigrants must not settle in any territory bordering the United States. New presidios, garrisoned by convicts serving out their prison sentences through military service, were established to check any such illegal immigration. Finally, the new law banned the further importation of slaves into Texas.

Actually, on September 15, 1829, President Vicente Guerrero had issued a directive abolishing slavery throughout the nation. (Guerrero’s gesture notwithstanding, slavery in Mexico would continue until the 1850s, though never as a legal institution.) Concerned about an immigration policy that seemed to be going astray, Guerrero had sought to dissuade Anglos from further colonization altogether by depriving them of their enslaved workforce. Political resistance from various quarters in Coahuila and Texas, however, ended up persuading Guerrero to exempt Texas from his national emancipation decree. Now, only seven months later, the Law of April 6, 1830, reinstated the ban on bringing human chattel into Texas–a point not lost on the American immigrants.

Читать дальше