In January 1833, Santa Anna ushered in a brief liberal era in Mexican politics when he was elected president as a Federalist. Back in favor, the liberals in Coahuila y Tejas and the Viesca brothers immediately arranged for the state legislature to petition the national government for the repeal of the Law of April 6, 1830. Now they had more helpful allies in Mexico City, among them Gómez Farías, whom Santa Anna appointed as his acting president before retreating to his hacienda in Vera Cruz, and Lorenzo de Zavala ( Figure 3.4), the legislator from Yucatán who still held interests in Texas lands for which he sought settlers from the United States. Working alongside the Federalists in Mexico City was Stephen F. Austin, who had arrived there following the consultation of April 1833. Ultimately, effective May 1834, Mexico’s senate revoked the section in the Law of April 6, 1830, that had curtailed the immigration of Anglos into the Mexican nation.

Figure 3.4 Lorenzo de Zavala. University of Texas at San Antonio Libraries Special Collections, Institute of Texan Cultures at San Antonio (MS 362: 76‐31).

Austin failed, however, to gain the separation of Coahuila and Texas. And when officials discovered letters between him and the San Antonio ayuntamiento encouraging Texas’s separation from Coahuila, they threw Austin in prison (early in 1834). Nonetheless, the state and national governments abided by their previous stand on colonization, and liberal legislation continued to emanate from Coahuila. New acts recognized the acceptance of English as a legal language of the state, permitted the extension of empresario contracts, expanded the number of local courts, and provided for trial by jury. The Coahuilan legislature also raised Texas’s representation in the state congress and increased the number of departments in Texas to three. Actually, the district of Nacogdoches, which extended from the watershed between the Brazos and the Trinity rivers to the Sabine, had been created in 1831 to accommodate the rise in the Anglo population. In order to allow more self‐autonomy in the province, the legislature in 1834 established the Department of Brazos, with its capital at San Felipe de Austin, which extended from the Nacogdoches district to a north‐south line from the coast to the Red River, just east of the Béxar and Goliad settlements. The third zone, the Department of Béxar, included San Antonio and extended to the Nueces River.

The Ineffectiveness of the Law of April 6, 1830

These changes point starkly to the ineffectiveness of the Law of April 6, 1830. Because Mexican officials had not been strict in interpreting the provisions of the decree, Anglos had continued to come into those colonies whose empresarios had imported the minimum one hundred families by the time the Centralists enacted the law. In addition, two empresario groups from Ireland persisted in their efforts to complete contracts they had acquired in the late 1820s; Centralists, after all, looked favorably upon European immigration as a way to people Texas. James McGloin and John McMullen brought several Irish families to the Nueces River area and founded San Patricio in 1831. Three years later, James Power and James Hewetson located colonists in the place that became modern‐day Refugio, Texas.

At the same time, the Galveston Bay and Texas Land Company, a land‐speculating corporation from the eastern United States that the empresarios Vehlein, Burnet, and de Zavala had commissioned to complete their contracts, continued to advertise the availability of its properties in Texas, even though the Law of April 6, 1830, had prohibited the further disposal of such lands. Thus, the company sold invalid land certificates to buyers. Despite the company’s fraudulent activities, it brought several European families into Texas in the early 1830s. Because the new arrivals were not Americans, Mexican officials ultimately accepted and resettled them elsewhere in Texas.

For his part, Sterling C. Robertson continued to claim ownership of the original Leftwich/Texas Association contract. Though Stephen F. Austin contested the contract, convincing the legislature at one point that the Robertson contract was invalid and that it should therefore be allotted to himself, Robertson persuaded the authorities in 1834 that he had brought to Texas the required one hundred families before the Law of April 6, 1830, had been effected. Despite the dispute, Robertson successfully settled numerous families while the Centralists remained in power.

Finally, many immigrants had arrived in Texas illegally during the early 1830s, hoping to start afresh as merchants, lawyers, land speculators, politicians, squatters, trappers, miners, artisans, smugglers, or jacks‐of‐all trades. But with the dilution of the Law of April 6, 1830, the stream of Anglo American immigration into Texas became a torrent. By 1834, it is estimated that the number of Anglo Americans and their slaves exceeded 20,700. This figure might well have represented the doubling of the number of Americans in Texas just since 1830.

Multicultural Society

Anglos

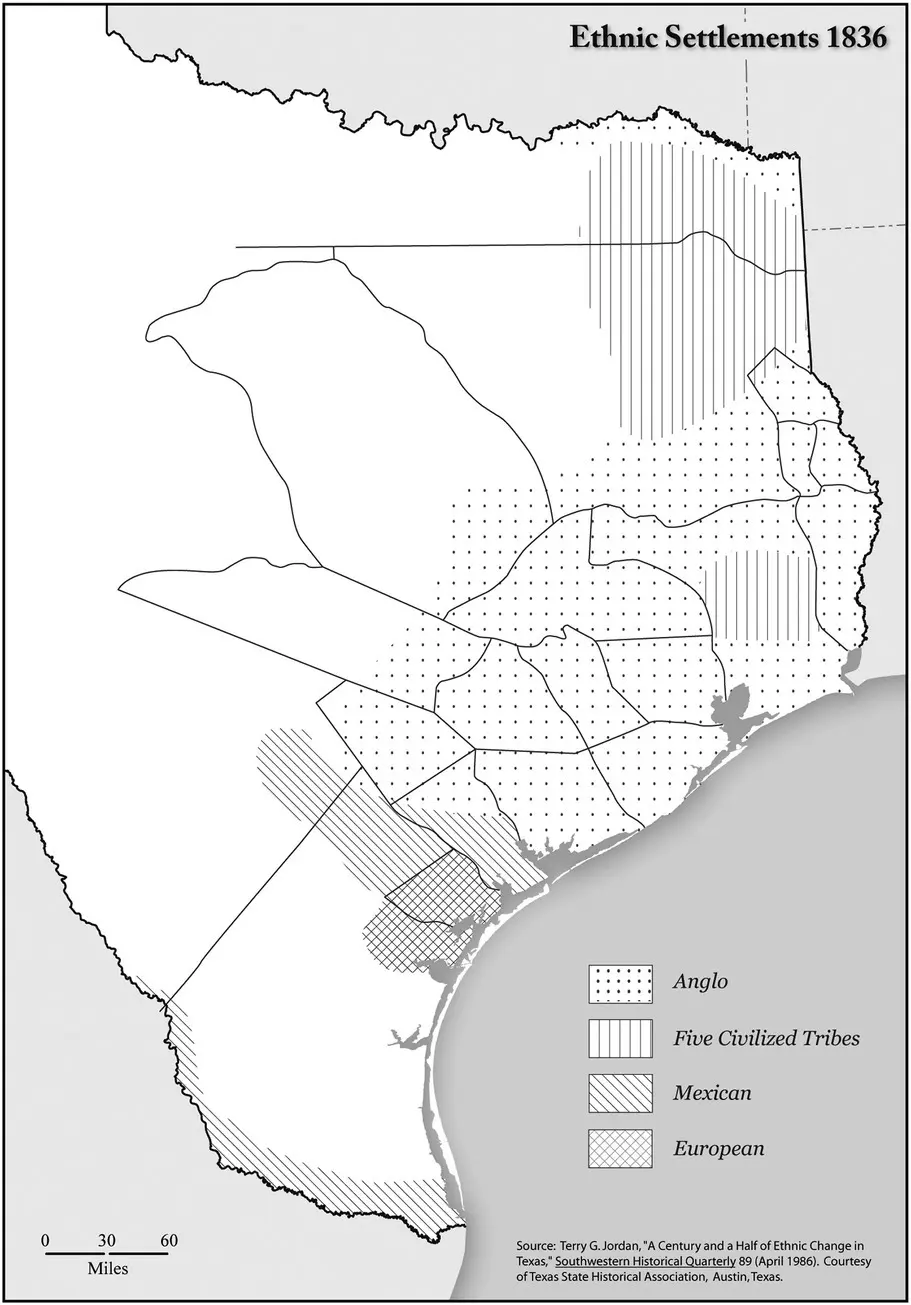

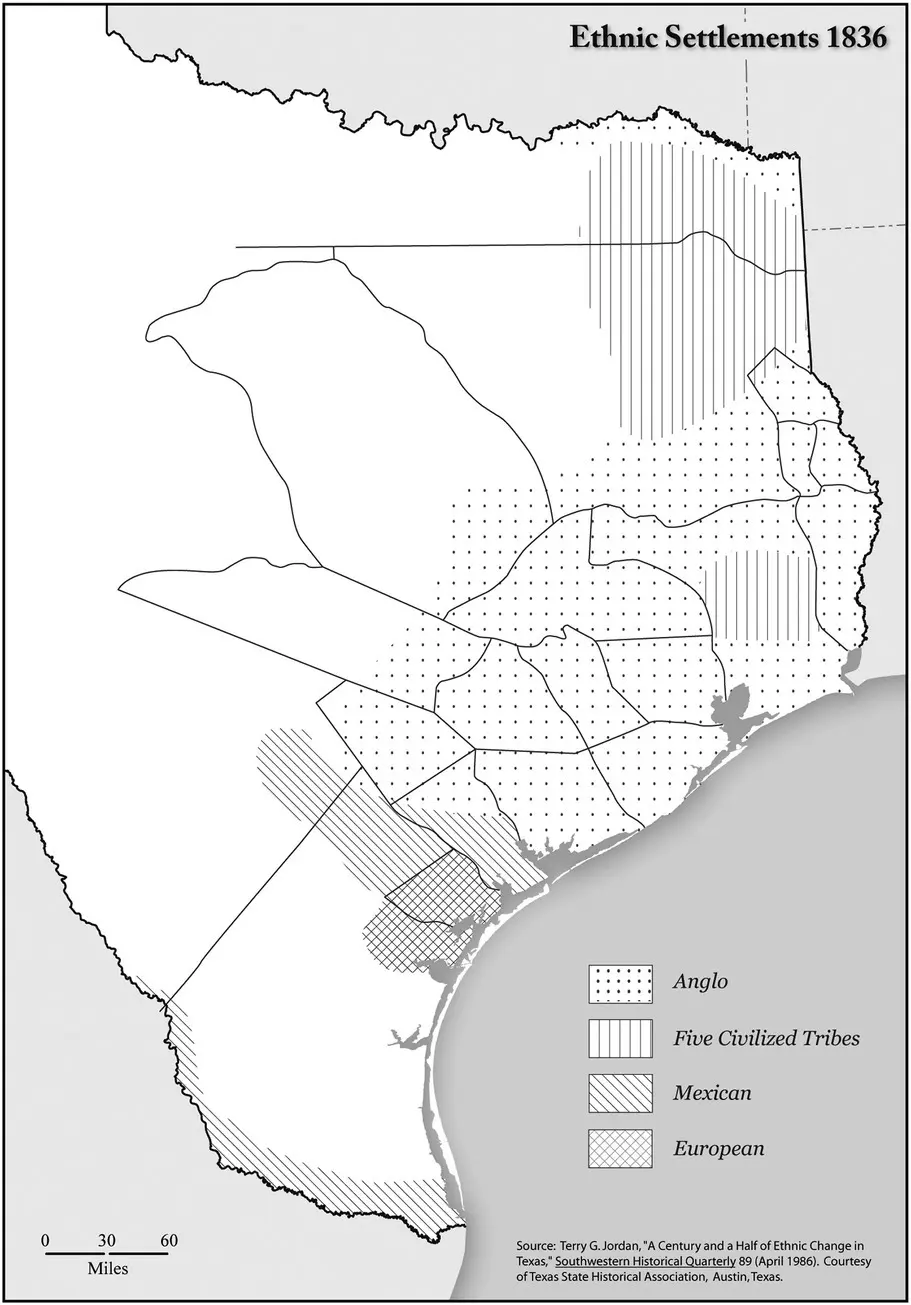

As one would expect, the number of towns in Texas increased–from three in 1821 to twenty‐one by 1835–most of them inhabited by the Anglo newcomers. The principal towns included San Felipe de Austin, in Stephen F. Austin’s first colony, Gonzales, in Green DeWitt’s grant, Velasco, on the Brazos (near present‐day Freeport), and Matagorda, on the mouth of the Colorado River. Figure 3.5shows the settlements in 1836 by ethnicity.

For all Texans, life consisted of a battle for survival, largely against the same odds the pobladores had faced before 1821. Basic goods such as clothing, blankets, and footwear were not readily available in Texas, but many immigrants had known enough to bring such items with them. Material for homemade apparel came either from animal skins or from cloth made on spinning wheels, devices some people had managed to import. Necessarily, the colonists used local resources such as stones, mud, or timber to construct log cabins or other types of shelter that ordinarily consisted of no more than two rooms (with dirt floors). Pioneers similarly lived off the land, hunted wild game, fished, planted small gardens, and gathered natural produce such as nuts and berries.

Figure 3.5 Ethnic settlements, 1836. Terry G. Jordan, “A Century and a Half of Ethnic Change in Texas,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly 89 (April 1986).

Courtesy Texas State Historical Association, Austin, Texas.

Anglos managed to convert parts of their grants into farmsteads, though agriculture as a gainful enterprise in Texas developed sluggishly. Early on, farming earned one barely the minimum standard of living, but by the late 1820s, cash‐crop farming in Austin’s colony and sections of East Texas began to reap better rewards. With slaves and imported technology at their disposal, some Anglos planted and processed cotton for new markets outside the province. One prominent scholar estimates that Anglos’ farms by 1834 shipped about 7000 bales of cotton (to New Orleans) valued at some $315,000.

Because hard currency did not circulate in the province, people bartered to obtain needed commodities and services, using livestock, otter and beaver pelts, and even land to complete their transactions. Improvising, Anglos found numerous ways to earn an income, among them smuggling. The tariff laws that exempted Anglo products during the 1820s had not applied to all imports (generally, codes excluded household goods and implements), so Anglos brought merchandise illegally into Texas. From there, some even brazenly shipped the products south to Mexican states or west to New Mexico.

Читать дальше