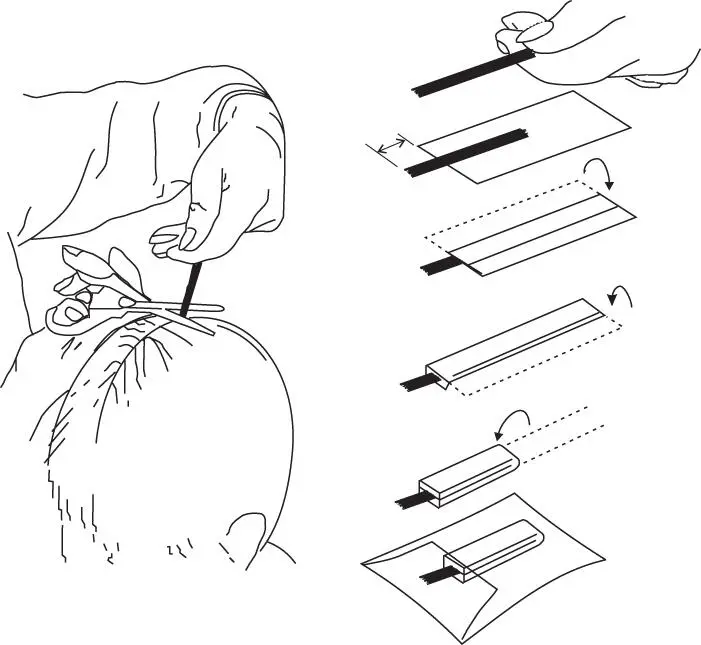

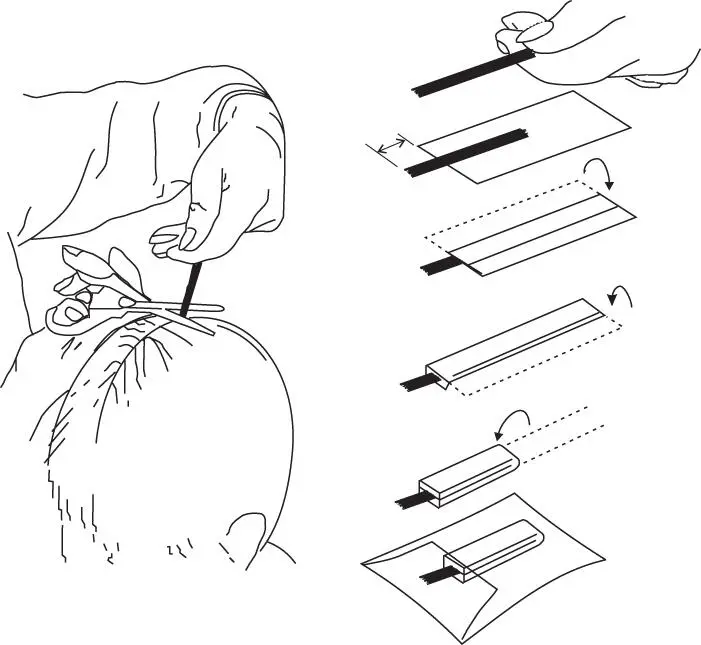

The ideal sample is collected from the vertex (the crown) of the head by cutting approximately 2 mm from the scalp

Take a sample of hair about the thickness of a pencil (100–200 hairs)

Pinch the hair tightly with the fingers and tie with cotton thread at the root end before cutting

Cut the sample as close as possible to the scalp, making sure the scissors are level with the scalp

Still holding the sample tightly, align the cut root ends of the sample and carefully place flat on a piece of aluminium foil with the cut root ends projecting about 15 mm beyond the end of the foil

Mark the root end of the foil and fold the foil around the hair and pinch tightly to keep in place

Fold the foil again in half lengthwise

Place the sample in a tamper-proof envelope. Complete and sign the request form, making sure that the donor also signs if necessary. If there are special instructions that do not appear on the form, but are felt relevant, make a note on a separate sheet and enclose with the sample

Nail clippings may be used to monitor uptake of antifungal drugs such as itraconazole and terbinafine (Leyden, 1998). In post-mortem work, whole nails should be lifted from the fingers or toes. This provides an even longer potential window for detecting exposure than hair. However, relatively little is known about the mechanisms of uptake and retention or drugs and metabolites in nail. In addition, the slower growth rate of nail, especially toe nail, as compared to hair makes segmental analysis, and hence interpretation of quantitative results, virtually impossible (Krumbiegel et al ., 2016; Solimini et al ., 2017).

Figure 2.2 Schematic of head hair collection

Bone marrow aspirate may be useful in the identification of certain poisons in exhumations, for example, where all soft tissue has degenerated (Orfanidis et al ., 2018). As with synovial fluid and pericardial fluid, bone marrow is normally within a relatively protected environment, and thus may also provide a valuable sample for drug screening or for corroborative ethanol measurement, for example, in the event that other samples are not available (Maeda et al ., 2006; Cartiser et al., 2011; Tominaga et al ., 2013). Analysis of bone itself may be useful if chronic poisoning by arsenic or lead, for example, is suspected.

Possible injection sites should be excised, packaged individually and labelled with the site of origin. Appropriate ‘control’ material (i.e. from a site thought to not be an injection site) of similar composition should be supplied separately.

Such material, which may include tablets, powders, syringes, infusion fluids, infusion lines, bandages, foodstuffs, drinks, and so forth, may give valuable information as to the poison(s) involved in an incident, and should be packaged separately from any biological samples. This is especially important if volatile compounds are involved. If police attend a scene these materials may find their way to a forensic laboratory rather than accompanying the patient.

All items should be labelled and packed with care. Scene residues may be particularly valuable when investigating deaths that may involve medical, dental, veterinary, or nursing personnel, who may have access to agents that are difficult to detect once they have entered the body, and in deaths that have occurred in hospital. Investigation of deaths occurring during or shortly after anaesthesia should include the analysis of the anaesthetic(s) used, including inhalational anaesthetics, in order to exclude an administration error. Needles must be packaged within a suitable shield to minimize the risk of injury to laboratory and other staff.

2.4 Sample transport, storage, and disposal

It is usually advisable to contact the laboratory by telephone in advance to discuss urgent or complicated cases. Most specimens, particularly blood and urine, may be sent by post if securely packaged in compliance with current regulations. However, if legal action is likely to be taken on the basis of the results, it is important to be able to guarantee the identity and integrity of the specimen from when it was collected through to the reporting of the results. Thus, such samples should be protected during transport by the use of tamper-evident seals and should, ideally, be submitted in person to the laboratory by the coroner's officer or other investigating personnel. Chain of custody is a term used to refer to the process used to maintain and document the history of the specimen ( Box 2.4).

Box 2.4Chain of custody documents

Name of the individual collecting the specimen(s)

Name of each person or entity subsequently having custody of it, and details of how it has been stored

Date(s) the specimen(s) collected or transferred

Specimen or post-mortem number(s)

Name of the subject or deceased

Brief description of the specimen(s)

Record of the condition of tamper-evident seals

Fully validated assays must include data on the stability of the analyte under specified sample collection and storage conditions (van de Merbel et al ., 2014; Reed, 2016). In the absence of other information, biological specimens should be stored at 2–8 °C prior to analysis, if possible, and ideally any specimen remaining after the analysis should be kept at 2–8 °C for 3–4 weeks in case further analyses are required. In view of the medico-legal implications of some poison cases (for example, if it is not clear either how the poison was administered, or if the patient dies) then any specimen remaining should be kept (preferably at –20 °C) until investigation of the incident is concluded. Unfortunately, there are few stability data for whole blood specimens, let alone for post-mortem specimens.

Table 2.9 Some drugs, metabolites, and other poisons unstable in whole blood or plasma (data from Peters, 2007 and from Mata, 2016)

| Volatile agents |

Aerosol propellants, anaesthetic gases, carbon monoxide, cyanide, ethanol, ethchlorvynol, mercury, methanol, nicotine, organic solvents, paraldehyde, volatile nitrites (amyl nitrite, etc.) |

| Non-volatile substances |

Acyl (ester) glucuronides, amiodarone, aspirin, bupropion, carbamate esters (e.g. physostigmine, pyridostigmine), ciclosporin, acyanide, esters (e.g. 6-AM, benzocaine, cocaine, diltiazem, diamorphine, GHB, pethidine, methylphenidate, procaine, succinylcholine), N -glucuronides (e.g. olanzapine N -glucuronide), insulins, insulin C-peptide, LSD, nitrobenzodiazepines (clonazepam, flunitrazepam, loprazolam, nitrazepam and their 7-amino metabolites), glyceryl trinitrate and other nitrates and nitrites, nitrophenylpyridines (e.g. nifedipine, nisoldipine), olanzapine, N -oxide metabolites, S -oxide metabolites, paracetamol, peroxides and other strong oxidizing agents, phenelzine, phenothiazines, bpiperazines, proinsulin, quinol metabolites (e.g. 4-hydroxypropranolol), rifampicin, sirolimus, a N -sulfate metabolites (e.g. minoxidil N -sulfate), tacrolimus, athalidomide, thiol-containing drugs (e.g. captopril), thiopental, zopiclone |

aRedistributes between plasma and erythrocytes on standing (use whole blood)

bParticularly those without an electronegative substituent at the 2-position

With regard to drugs, some compounds such as clonazepam, cocaine, nifedipine, nitrazepam, thiol drugs, and many phenothiazines and their metabolites are unstable in biological samples at room temperature ( Table 2.9). Synthetic piperazines, for example, are generally unstable in whole blood, for example (Lau et al ., 2018). Exposure to sunlight can cause up to 99 % loss of clonazepam in serum after 1 h at room temperature. Covering the outside of the sample tube in aluminium foil is a simple precaution in such cases. N -Glucuronides such as olanzapine N -glucuronide are unstable and may be present in plasma at high concentration; on decomposition the parent compound is reformed. Some compounds, notably olanzapine, appear relatively stable in plasma, but are dramatically unstable in haemolyzed blood.

Читать дальше