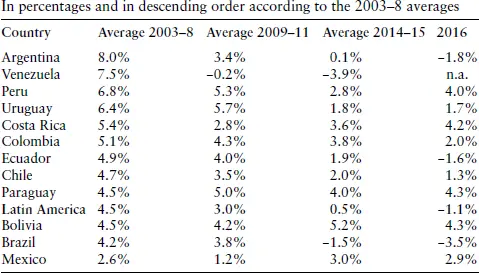

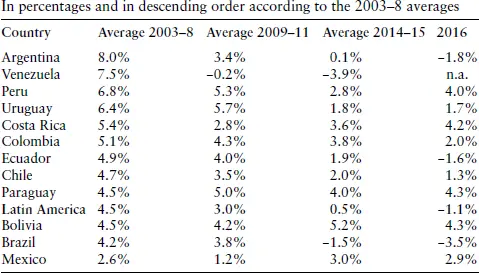

Countries in the region managed to contain the effects of the global financial crisis and to ensure continued economic growth between 2002 and 2013 on account of two main factors. The first was the regulatory role of the state, which was stronger in Latin America than in the United States and Europe, especially regulating financial markets after the crisis of the 1990s (or the “Tequila Effect”), the crisis of the real in Brazil in 1999, and the collapse of the banking system in Argentina in 2001. The Cardoso and Kirchner administrations introduced regulatory measures into the financial systems of Brazil and Argentina, respectively, that seem to have been more effective than those in the United States or Europe. These administrations thus adapted more efficiently to the systemic volatility of global financial markets. Secondly, there was a transformation in patterns of world trade, and South–South trade partnerships (both with Asia and within Latin America) became more significant than the classic dependency on the United States and Europe.

Table 1.1:Rates of Year-to-Year Change in Gross Domestic Product, 2003–2016

Note: n.a. = not available

Source: The authors’ own calculations, based on data in ECLAC (2018)

At the same time, however, although democracy, a key issue in Latin American history, has been stabilized throughout Central and South America, its legitimacy has been weakened recently. In 1976, there were only three democracies in the region. Now democracy is generalized throughout Latin America (with the case of Cuba remaining debatable), at least if we apply the standards of democracy used in Florida during the United States presidential election in 2000, and if we set aside the 16 recent presidential ousters in the region, including two coups, both quickly reversed. According to Latinobarómetro, the rate of support for democracy as a form of government preferable to any other reached its highest level (61 percent) in 2010. But a series of experiences and events have worn away at confidence in democracy and especially in the political system that supports it. Support for democracy thus fell to 53 percent in 2017. By contrast, support for authoritarian regimes has increased under conditions of corruption and organized crime. This mainly affects parliaments and political parties whose legitimacy is very weak (Cohen et al., 2017). Today the crisis of the state and of the political system are central to the problems that Latin America is confronting.

Rates of poverty, the other “disease” from which Latin America has traditionally suffered, were reduced from 45.9 percent of the region’s population in 2002 to 30.7 percent in 2017. Extreme poverty also decreased during the same period, from 12.4 percent to 10.2 percent (ECLAC, 2018b: 88). If we also factor in the improvement in one of the main indicators of health and the near universalization of primary school education (despite the poor quality of many schools in the region), we see a Latin America that differs markedly from its traditional image.

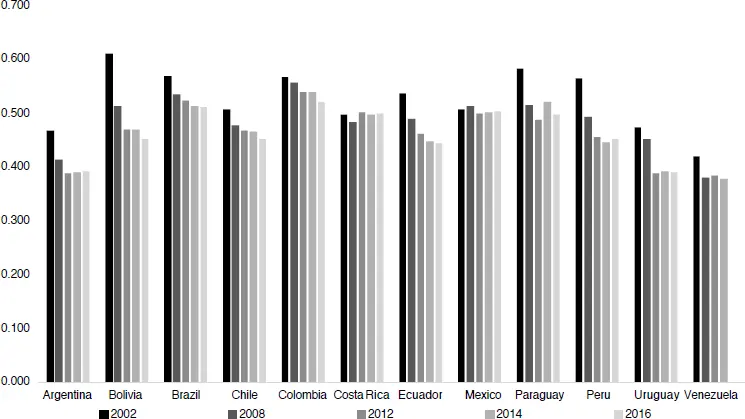

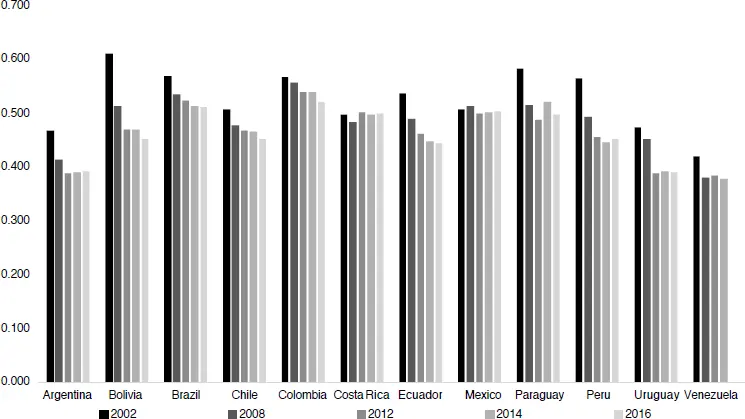

The Gini coefficient, which measures inequality, was 0.469 and 0.467 in 2015 and 2016, respectively, for 17 Latin American countries (ECLAC, 2017: 52 and ECLAC, 2018b: 44). According to the same source, this index for the region decreased by an average of 1.5 percent yearly between 2002 and 2008, but it only decreased by 0.4 percent yearly between 2014 and 2016 (ECLAC, 2018b). The reduction in levels of inequality was caused by an improvement in wages in key sectors and an increase in monetary transfers from governments to these sectors. This tendency has, however, begun to be reversed during the last few years. Figure 1.1 shows the evolution and slow decrease in inequality in selected Latin American countries between 2002 and 2016.

We suggest that these phenomena, particularly the decrease in poverty, were caused in large part by the greater presence of the state as a central player in processes of development, with a strategic orientation, a willingness to invest public funds in infrastructure, education, and healthcare, and a commitment to redistributive policies like the program known as Bolsa Família in Brazil. 1In fact, the neoliberal model of unrestricted national participation in globalization, a model generated by the market, collapsed both economically and socially around the beginning of the twenty-first century in most Latin American countries. (The bank freeze in 2001 in Argentina is the clearest symbol of this collapse.) A new model then emerged, a model that proclaimed itself neo-developmentalist , and that was centered on the state but oriented toward competition in the global market. This model is apparently very similar to the model of development that prevailed in East Asia from 1960 to 1980, the period of East Asia’s “economic takeoff.”

Figure 1.1: Gini Coefficient of Inequality: Selected Latin American Countries, 2002–2016

A more complex and internally differentiated picture emerges when we consider the Human Development Index (HDI). Table 1.2shows tendencies in and differences between countries according to their levels of human development. Overall, the region has a high level of human development. Chile and Argentina are the only countries with a very high level of human development, and only Paraguay and Bolivia have average levels of human development. All countries witnessed increases in HDI, except Venezuela, where the HDI began to decrease in 2013.

In terms of the factors that the HDI takes into account (education, health, and incomes), Chile has the highest rates of income measured as a factor of HDI (0.812 in 2015), followed by Argentina and Uruguay (0.807 and 0.794, respectively, in 2015). Argentina leads the region in rates of education measured as a factor of HDI (0.808 in 2015), while Chile and Uruguay occupy second and third place in the region. Finally, in rates of health measured as a factor of HDI, Chile is in first place, followed by Costa Rica and Uruguay, with Argentina in fifth place, after Mexico, in 2015.

The transformation in approaches to development, from neoliberalism to neo-developmentalism, was caused in large part by the resistance mounted by vast swathes of the population against the exclusionary policies that sought to force Latin America to incorporate itself into the global economy, policies that benefitted old and new elites. Another key factor leading to the emergence of a new set of policies and politics was the demand for the recognition of oppressed cultural identities. This demand was made especially in Bolivia, Ecuador, and Peru, but members of other ethnic groups also sought recognition in Chile, Mexico, and Colombia. A combination of social movements opposing exclusion and identitarian movements opposing institutionalized racism led to the emergence of a new constellation of political actors, including Bolivarian regimes (in Venezuela, Ecuador, and Nicaragua), nationalist and indigenous regimes (in Bolivia), neo-Peronism or Kirchnerism (in Argentina), and progressive governments like those of the Partido dos Trabalhadores or PT (in Brazil) and the Frente Amplio (in Uruguay). A process of widespread social change accompanied these political transformations, leading to the affirmation of human rights, the growth of feminist movements and improvements in living conditions for women, and increased multicultural awareness in society and politics. Moreover, the emergence of new political actors opposing the United States’ control of the region led to a new geopolitical role for Latin America in the world. The region has diversified its economic and political relationships with countries including China, Japan, South Africa, and, to a lesser extent, Russia, while also encouraging closer ties with the countries of the European Union. Nevertheless, the presence of the United States remains significant, especially in Mexico, Central America, and Colombia.

Читать дальше