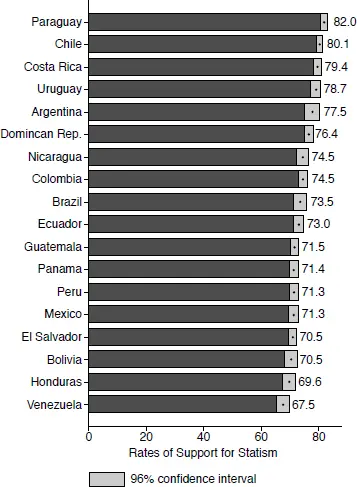

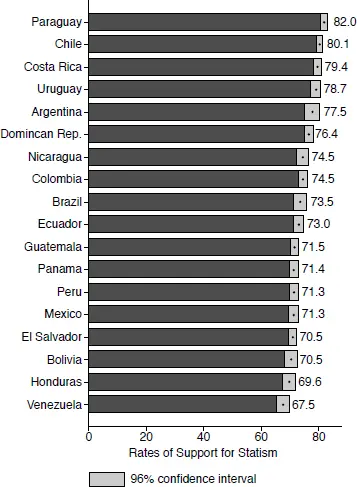

Figure 1.2: Average Levels of Support for Statism: Selected Latin American Countries, 2010

Paradoxically, it seems that one of the reasons for the demand that the state play such a key role is clearly related to the weakness of the state as it seeks to confront and resolve demands for social integration and development. But this demand also follows from a profound distrust of economic and political elites in virtually all Latin American countries.

In this context, para-institutional mechanisms come to the fore, with their ability to mediate between society and the state, thus helping to enhance leaders’ charisma. Given the weakness of institutions, the relation between the state and social organizations becomes informal rather than formal, and it acquires clientelist and charismatic traits, which then inform everyday relationships and introduce anomalies into formal institutions, further enabling corruption. The availability of informal alternatives, caused by failed socioeconomic policies in the past, favors the emergence of a fertile but limited relationship between charismatic leaders and society. In this way, an inability to generate satisfactory living conditions for the people decisively contributes to the demand for, and the installation of, charismatic leaders with populist traits.

We can conclude that, in this context, these kinds of processes make the presence of charismatic domination possible. The leader’s identification with the people is a key feature in the phenomenon of Latin American charismatic politics. In his origins as well as his image and his dramatic and complicated trajectory, the leader must identify as one more member of the people in order to recast himself as a symbol of the people. In this way, an affective unity is created, one that is inseparable from the idea of “the people.” The leader is one with the people because he is part of the people; he himself is the people. He lives for, and can sacrifice himself for, the people. In this sense, the people are reified, materialized in the image of the leader. The process of political change is motivating, a reason for living. But charismatic reason, as Weber said, is an epiphany in and of itself.

In this sense, in order to understand neo-populist movements in Latin America, it is crucial to understand the relationship between charismatic leaders and society in the region. These movements arise when institutions are structurally weakened, when processes of social integration and national cohesion are limited, when public insecurity is widespread, and when citizens’ expectations are frustrated. But in addition to noting their commitment to social democracy, it is important to mention that none of these charismatic leaders disavowed or questioned electoral democracy either. The latter was, in fact, fundamental to their legitimacy.

On the other hand, today’s society of information and communication has transformed the kinds of action in which charismatic leaders engage. The new demands made by communities, like the new forms of action taken by leaders, are increasingly expressed through the internet and through the multiple forms of communication that tend to proliferate online. The leader is no longer on his own in the public square, but rather in a mediated public sphere, in multiple and diverse public spaces of communication.

It is worth mentioning that the crisis of neo-developmentalism is inseparable not only from national and global socioeconomic conditions, but also, more specifically, from the fate of charismatic leaders, from what they have experienced and are experiencing. They disappeared for various reasons (the deaths of Chávez and Néstor Kirchner, the electoral defeats of others like Correa or Lula, and illnesses, among others), and their disappearance affected the unfolding of neo-developmentalist processes. They are among the fundamental factors that explain the current crisis of these political orientations toward development and democracy (Calderón and Moreno, 2017 [2013]).

The Neo-Developmentalist Model and the New Globalization: China and the Global South

China’s rise to a prominent position in the new world economy created an enormous market for the kinds of exports that still characterize most Latin American economies: agricultural products, raw materials, and energy. The more China imports from and invests in Latin America and the rest of the Global South, the more it spurs economic growth in the Global South, which becomes an expanding market in its own right. Latin America took advantage of the boom in commodity prices linked to the explosion of demand from China, India, and other large markets; it modernized its primary sector, using new technologies of information and genetically modified agriculture as well as new business strategies. A new model arose, one that we have called informational extractivism . Although information technologies did not completely transform the productive system, they did transform the production of soy, the production of meat, the creation of energy and gas, and the mining of precious metals (like lithium in Chile, Argentina, and most recently Bolivia), raising both quality and productivity in a virtuous circle of economic growth. Nevertheless, the success of neo-developmentalism followed from two premises that were soon shown to be fragile: first, that global demand for commodities would continue to increase; and, second, that the prices of these commodities would remain high. Reclaiming its redistributive role through new policies, the state could avoid opposition thanks to the fact that society remained active, was increasingly informed, and significantly increased its participation in consumption.

The Crisis of Neo-Developmentalism

Almost all countries in Latin America were unable to engage in a complete informational transformation of their economies and societies, one that would have led, for example, to the transformation of research, higher education, and policies for the promotion of innovation. This inability meant that the growth of the region’s economies remained almost entirely dependent on exports from the extractive sector. As soon as China’s growth slowed and the prices of commodities fell, Latin American economies revealed their vulnerability to the fluctuations of the global economy. Even Brazil, the region’s most diversified economy, did not have sufficient knowledge to change its export patterns and add value to goods and services. While Latin America largely learned to manage financial volatility, it has not been able to do the same with the volatility of trade. As a result, Argentina’s economy, for example, fell 2.5 percent in real terms in 2014, and the same happened in Brazil in 2015 (−3.5 percent), while rates of growth slowed considerably throughout the region, except in Bolivia and Peru. 2015 was the first year of the twenty-first century in which the Latin American economy did not grow. While governments for a time continued to engage in high levels of public spending (something fundamental for social stability), the renewed threat of inflation, poised to exceed economic growth, forced these governments to impose austerity, especially the administration of Dilma Rousseff in Brazil in 2014. This undermined the popularity of governments in Brazil, Venezuela, and, to some extent, Bolivia and Argentina. Neo-populist governments won electoral victories but by ever smaller margins and with decreasing legitimacy.

Moreover, the neo-developmentalist model of development was based on the maintenance of economic growth and redistribution at all costs; it focused on the development of productive forces and on the improvement of the material living conditions for populations, especially for their poorest members. This productivist model ignored the environmental and social costs that it entailed. Enormous metropolitan areas became barely hospitable for most of the population, with rates of urbanization above 75 percent in the majority of Latin American countries. The conditions of housing, transportation, urban recreation, pollution, and the environment all deteriorated rapidly. While traditional measures of human development (health, education, and salaries) improved, a model of “inhuman development” arose and negatively affected the quality of life of most of the population. The criminal economy, brutal violence, pervasive crime, and the terror caused by gangs became the most significant problems affecting everyday life in every Latin American country. The media contributed to public panic, covering atrocious threats to daily life for ordinary citizens. Political corruption contributed to a shared sense of defenselessness.

Читать дальше