This basic outline of gene expression leaves many important questions unanswered. How does mRNA synthesis begin and end at the correct places and on the correct strand in the DNA? Similarly, how does translation start and stop at the correct places on the mRNA? What actually happens to the tRNA and ribosomes during translation? What happens to the mRNA and proteins after they are made? The answers to these questions and many others are important for the interpretation of genetic experiments, so we will discuss the structure of RNA and proteins and the processes by which they are synthesized in more detail.

The Structure and Function of RNA

In this section, we review the basic components of RNA and how it is synthesized. We also review how structure varies among different types of cellular RNAs and the role each type plays in cellular processes.

There are several different classes of RNA in cells. Some of these, including mRNA, rRNA, and tRNA, are involved in protein synthesis. Each of these types of RNA has special properties, which are discussed below. Others are involved in regulation, replication, and protein secretion.

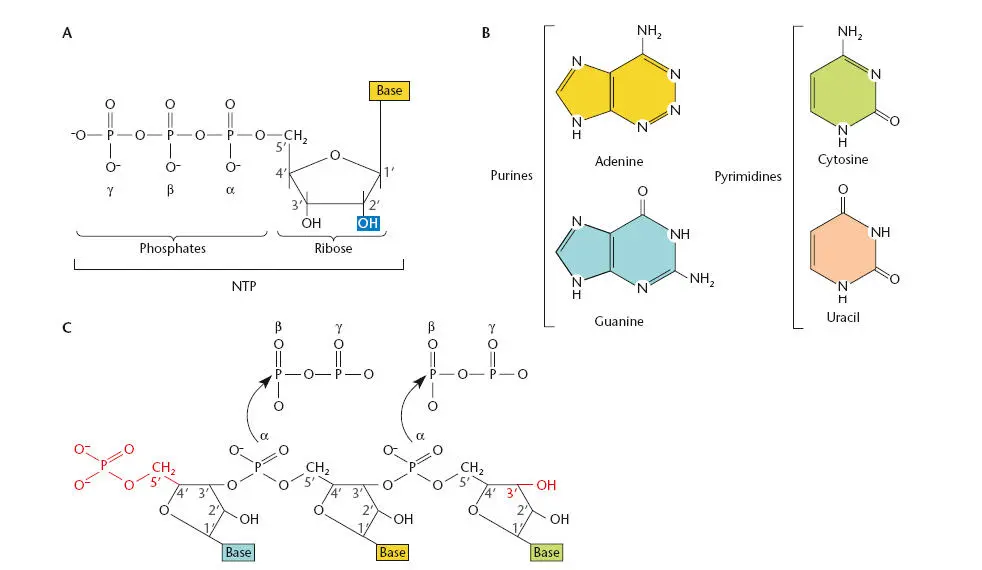

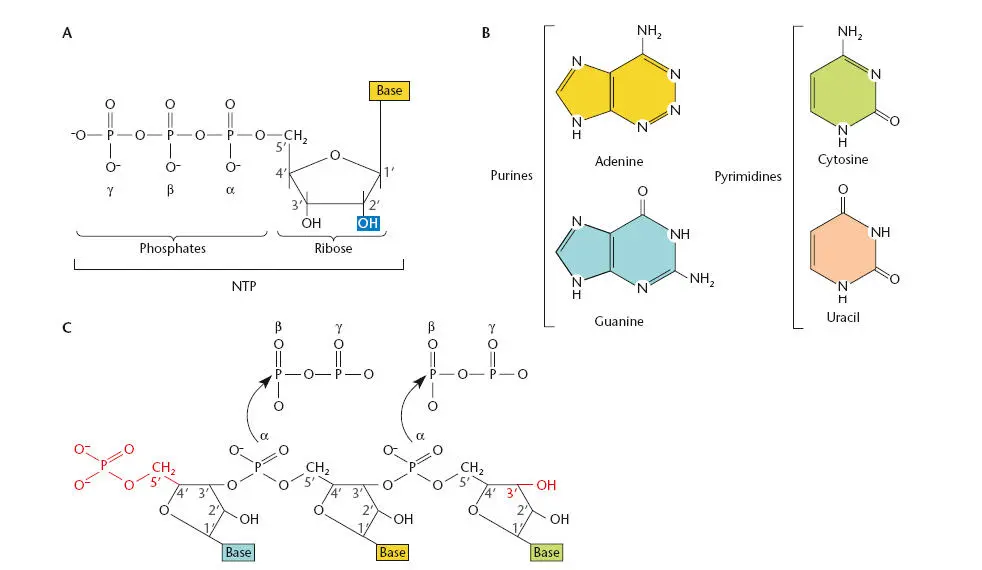

RNA is similar to DNA in that it is composed of a chain of nucleotides. However, RNA nucleotides contain the sugar ribose instead of deoxyribose. These five-carbon sugars differ in the second carbon, which is attached to a hydroxyl group in ribose rather than the hydrogen found in deoxyribose (see Figure 1.2). Figure 2.1Ashows the structure of a ribonucleoside triphosphate(rNTP), which is the form that is used as a precursor during RNA synthesis.

RNA and DNA chains also vary in the bases that are present. Three of the bases—adenine, guanine, and cytosine—are the same, but RNA has uracil instead of the thymine found in DNA ( Figure 2.1B). The RNA bases also can be modified after they are incorporated into an RNA chain, as discussed below.

Figure 2.1Cshows the basic structure of an RNA polynucleotide chain. As in DNA, RNA nucleotides are held together by phosphates that join the 5′ carbon of one ribose sugar to the 3′ carbon of the next. This arrangement ensures that, as with DNA chains, the two ends of an RNA polynucleotide chain will be different from each other, with the 5′ end terminating in a phosphate group and the 3′ end terminating in a hydroxyl group. The 5′ end of a newly synthesized RNA chain has three phosphates attached to it because transcription initiates with an rNTP. As each new rNTP is added to the growing RNA chain, two phosphate groups are released so that the sugar phosphate backbone alternates between the ribose (to which the base is attached) and a single phosphate group.

According to convention, the sequence of bases in RNA is given from the 5′ end to the 3′ end, which is the direction in which the RNA is synthesized, by addition of the 5′ α-phosphate of an incoming nucleoside triphosphate to the 3′ hydroxyl end of the growing RNA chain. Also by convention, regions in RNA that are closer to the 5′ end in a given sequence are referred to as upstream, and regions that are closer to the 3′ end are referred to as downstream, because RNA is both synthesized and translated in the 5′-to-3′ direction.

Except for the sequence of bases and minor differences in the pitch of the helix, little distinguishes one DNA molecule from another. However, RNA chains generally have more structural properties than DNA and often are folded into complex structures that have important biological roles. Extensive base modifications can further change the structure of the RNA molecule.

All RNA transcripts are synthesized in the same way, from a DNA template. Only the sequences of their nucleotides and their lengths are different. The sequence of nucleotides in RNA is the primary structureof the RNA. In some cases, the primary structure of an RNA is changed after it is transcribed from the DNA (see “RNA Processing and Modification” below).

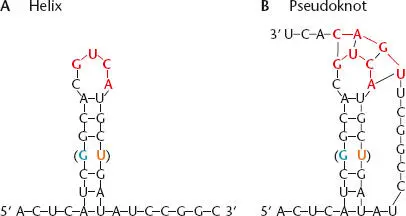

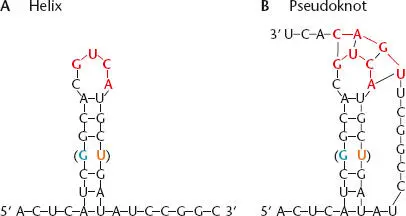

Unlike DNA, RNA is usually single stranded. However, pairing between the bases in different regions of the molecule may cause it to fold up on itself to form doublestranded regions. Such double-stranded regions are called the secondary structureof the RNA. All RNAs, including mRNAs, probably have extensive secondary structure.

Figure 2.1 RNA precursors. (A)A ribonucleoside triphosphate (rNTP) (the form of NTP used as a precursor for RNA) contains a ribose sugar, a base, and three phosphates. (B)The four bases in RNA. (C)An RNA polynucleotide chain with the 5′ and 3′ ends shown in red.

Figure 2.2shows an example of RNA secondary structure in which the sequence 5′-AUCGGCA-3′ has paired with the complementary sequence 5′-UGCUGAU-3′ somewhere else in the molecule. As in double-stranded DNA, the paired strands of RNA are antiparallel, i.e., pairing occurs only when the two sequences are complementary when read in opposite directions (5′ to 3′ and 3′ to 5′) and the double-stranded RNA forms a helix that is similar to a DNA-DNA helix, capped with a few unpaired residues called a loop; the helix plus the loop are sometimes called a hairpin. However, the pairing rules for double-stranded RNA are slightly different from the pairing rules for DNA. As in DNA, G pairs with C, and A pairs with U (which replaces T in RNA). In RNA, guanine can pair not only with cytosine, but also with uracil. Because these G-U “wobble” pairs do not share hydrogen bonds, as indicated in the figure, they contribute less substantially to the stability of the double-stranded RNA. Additional “non-Watson-Crick” pairings are also found in RNA; these often involve surfaces of the nucleoside other than the normal hydrogen-bonding edge.

Figure 2.2 Secondary structure in an RNA. (A)The RNA folds back on itself to form a helical element sometimes called a hairpin. The presence of a GU pair (in parentheses) does not disrupt the structure. (B)Different regions of the RNA can also pair with each other to form a pseudoknot (participating residues shown in red). In the example, the loop of the hairpin pairs with another region of the RNA.

Each base pair that forms in the RNA makes the secondary structure more stable. Consequently, the RNA generally folds so that the greatest number of continuous base pairs can form. The stability of a structure can be predicted by adding up the energy of all of the hydrogen bonds that contribute to the structure. By eye, it is often difficult to predict which regions of a long RNA will pair to give the most stable structure. Computer software (e.g., mfold [ http://mfold.rna.albany.edu/?q=mfold]) is available that, given the sequence of bases (primary structure) of the RNA, can predict the most stable secondary structure; however, the structure of complex RNAs is difficult to predict computationally because of interrupted base-pairing and non-Watson-Crick interactions.

Double-stranded regions of RNAs generated by base pairing are stiffer than single-stranded regions. As a result, an RNA that has secondary structure will have a more rigid shape than one without double-stranded regions. Also, the intermingled paired regions cause the RNA to fold back on itself extensively, facilitating additional tertiary interactions. One type of tertiary interaction occurs when an unpaired region (such as the loop of a hairpin like that shown in Figure 2.2) pairs with another region of the same RNA molecule. A structure like this is called a pseudoknot (rather than a real knot) because it is held together only by hydrogen bonds. Together, these interactions give many RNAs a well-defined three-dimensional shape, called their tertiary structure. Proteins or other cellular constituents often recognize RNAs by their tertiary structures.

Читать дальше