Rush into the Digital Revolution

The overall trend of the sovereign investor world is to invest in the digital future – whether existing funds seeking to facilitate a digital transformation, or new funds established with that goal from the beginning. What's interesting is that this is not a new phenomenon: the states have (always) been active in tech investments. Silicon Valley and Tel Aviv were largely the creation of the US and Israeli states. Many of the innovations we take for granted today – such as the Internet, cloud computing, and virtual reality – were fostered by state seed capital or driven by government agencies.

And this continues to be partly the case: in 2014, the Pentagon, the US Defense Ministry, teamed up with the CIA to invest in cybersecurity startups. The CIA has been running its Q-Telventure capital fund since 1999, with extensive investments in tech companies. This state–military link is particularly important for understanding the rise of startups in Israel and its famous Yozma program, which unleashed the technical miracle Start-up Nation. Not to mention that space, initially the sole preserve of governments, now hosts Blue Origin (Jeff Bezos), SpaceX (Elon Musk), and Virgin Galactic (Richard Branson), backed in part by sovereign investor cash.

One notable change in equity markets around the world can be laid at the feet of the patient, cash-rich sovereign investors: the dramatic decline in IPOs. The Financial Times headlined 2019's 10% drop from 2018 in capital raised in public listings, with the fewest flotations for three years. The massive investments by sovereign investors, eager to gain exposure to the digital economy, have enabled these tech stars to remain private far longer than would have been possible in the past (see the detailed discussion in the next chapter).

One result has been a dramatic drop off in IPOs; another, hefty pre-IPO valuations that are challenging for the tech giants to sustain in public markets. In the absence of patient, massive equity inflows from the sovereign investors, things may have played out quite differently. Others speculate that it was the arrival of SIFs into the market for late stage growth companies that enabled them to put off SEC scrutiny and meddlesome public shareholders, thereby shrinking public markets. Others see the mirror image, with the SIFs not as enablers but as driven to unicorns by the shrinking public markets.

Ironically, the largest IPO of 2019 was Saudi Aramco, which topped $2 trillion in market cap briefly after its listing. Nearly $30 billion in proceeds will largely fund PIF, which has as a goal the digital transformation of the economy and has heavily funded (via Vision Fund and directly) late stage tech stars such as Uber. In 2020, the oil price war with Russia and the economic impact of the coronavirus on the Saudi economy may cause PIF to redirect more proceeds to stimulus and funding deficits. But Vision 2030, the transformative digital future, remains in its sights.

The rest of this book will cover the tech investments of SIFs in detail. The most prominent example of this trend is Saudi Arabia and its Public Investment Fund (PIF), whose exceptionally large capital contribution to the Vision Fundhas consequently had a profound impact on the global tech startups and capital markets. PIF is the beneficiary of the country's oil wealth and, most notably, the beneficiary of proceeds from the flotation of Aramco, briefly the most valuable company on Earth (see Box: The IPO to end all IPOs).

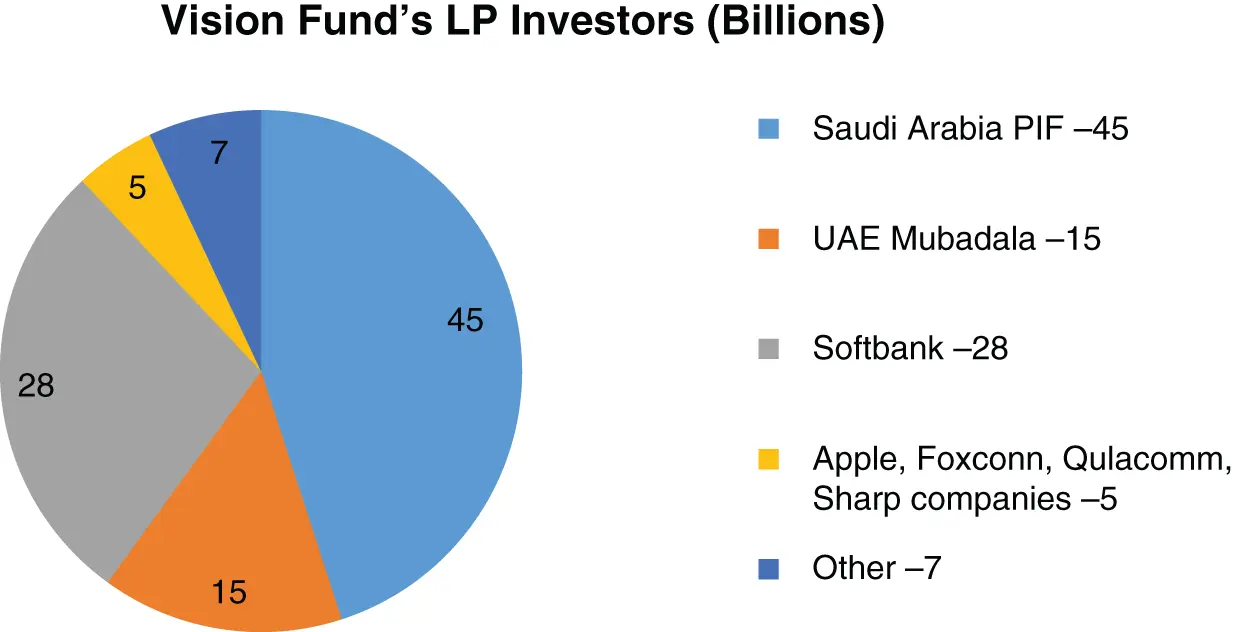

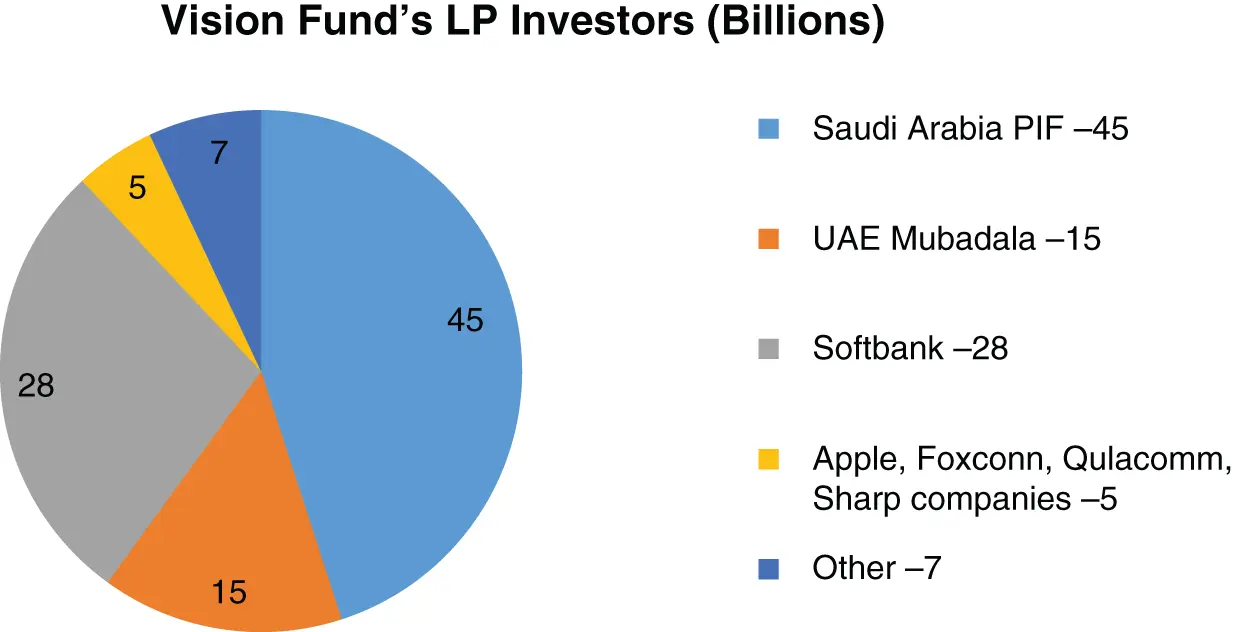

Saudi Arabia has successfully leveraged its resource-based capital in PIF to raise its profile as a major player in venture capital for tech companies. PIF committed $45 billion to the first Vision Fund's total raise of $100 billion (see Figure 1.5 ), at the time an unheard of fund size for venture capital – nearly double the amount raised by all other VC funds in a good year. Reportedly, PIF was contemplating a similar commitment to the second Vision Fund. The Fund also committed to a $500 million investment in Neom, the future oriented (flying taxis, robot dinosaurs) city Saudi Arabia is planning for its Red Sea coast.

Using its sovereign fund, Saudi Arabia has succeeded in drawing tech thought leaders to its “Davos in the Desert,” despite talk that its domestic policies were anathema to the Silicon Valley ethos. The link to Neom city is of note as well. It is possible that the reciprocal investment promised by Softbank, Vision Fund's sponsor, in Neom will elevate its chances of attracting additional tech sector players to the country. Such a result would mean that PIF had also indirectly propelled the digital transformation of the Saudi economy by securing an anchor investor in its show piece of the digital future (see the more detailed discussion in Chapter 5).

Figure 1.5 SIFs Lead $100 billion Vision Fund

Data Source: FT Research 2017.

Another case in point is the European Union, which is a latecomer to the world of sovereign investment funds and digital economy investments. With the rest of the world aggressively investing into tech ventures domestically and internationally, Europe has actually looked more like a net seller. Chinese buyers have acquired large robotics firms in Germany and Italy; in the UK, SoftBank bought the chip-maker ARM and one of its affiliates is set to bid on the UK's upcoming 5G auction. The UK's DeepMind, the AI pioneer that built the Alphago algorithm to beat the best human player in Go Chess, was sold to US Internet giant Google's parent company, Alphabet.

For Europeans, Apple of the US (and Samsung, from South Korea) are the most popular phones. Similarly, US companies dominate digital platforms in Europe: Facebook operates the most widely used social networks, Google rules online search and advertising, and Amazon reigns over e-commerce. Cloud infrastructure from Amazon and Microsoft is indispensable to Europe's companies. Meanwhile, China's Huawei produces the physical equipment on which Europe's digital economy runs. Driving home the extent of foreign digital dominance, EU officials had to call Los Gatos, California to ask US tech giant Netflix to lower its video streaming quality to prevent a European system crash during the coronavirus-induced surge in Internet traffic.

Things are set to change in 2020 and beyond. The European Union in February 2020 unveiled a plan to restore what officials called “technological sovereignty,” with more public spending for the European tech sector. With the global economy becoming ever more reliant upon digital technology, European leaders are concerned that the European economy is overly dependent on technology developed and controlled elsewhere. As Ursula von der Leyen, the president of the European Commission, the executive branch of the EU, said at a news conference: “We want to find European solutions in the digital age.” Hence new sovereign investment funds in Europe.

According to media reports in August 2019, EU staff have drafted a plan to launch a €100 billion ($110 billion) sovereign wealth fund, to be called the “European Future Fund.” The main goal of this proposed fund will be to invest into future “European tech champions,” which could potentially compete in the same league as China's BAT (Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent) or the US GAFA (Google, Apple, Facebook, and Amazon). Due to the complex EU politics, it is not clear that the fund will ever be realized; but the determination to compete with American and Chinese dominance, using a sovereign fund, in the future digital economy is clear.

Читать дальше