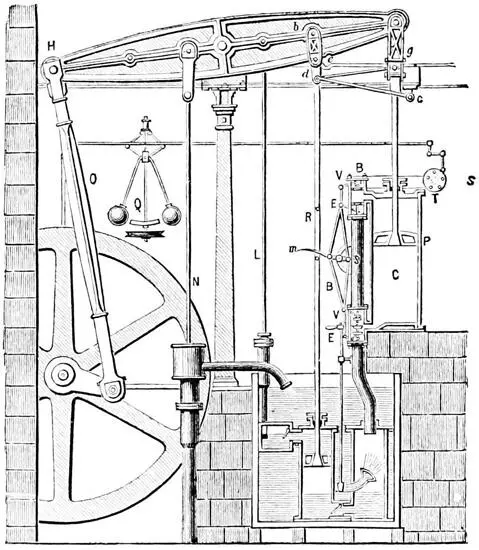

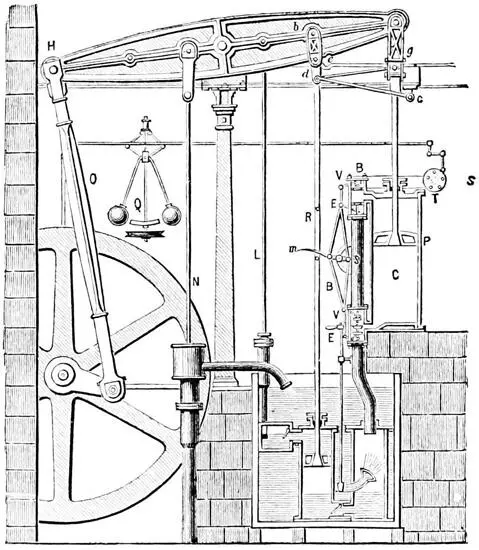

A cross section of a late eighteenth-century Boulton and Watt steam engine. The main cylinder, C, would have been bored by John Wilkinson, the piston, P, fitting snugly inside it to the thickness of an English shilling, a tenth of an inch.

As he began what would be a full decade of testing and prototype building and demonstrating and seeking funds (during which time he moved south from Scotland to the vibrantly industrializing purlieus of the English Midlands), Watt sought and was swiftly awarded a patent: Number 913 of January 1769. It had a deceptively innocuous title: “A New Invented Method of Lessening the Consumption of Steam and Fuel in Fire-Engines.” The modest wording belies the invention’s importance: once perfected, it was to be the central power source for almost all factories and foundries and transportation systems in Britain and around the world for the next century and more.

What is especially and additionally noteworthy, though, is that a historic convergence was in the making. For, living and working nearby in the Midlands, and soon to produce a patent himself (the already noted Number 1063 of January 1774, an exact one hundred fifty patents and exactly five years later than James Watt’s), was no less an inventor than John Wilkinson, ironmaster.

By then, Wilkinson’s amiable madness was making itself felt throughout the ferrous community: all came to learn that he had made an iron pulpit from which he lectured, an iron boat he floated on various rivers, an iron desk, and an iron coffin in which he would occasionally lie and make his frightening mischief. (Women were in plentiful attendance, despite his being a somewhat unattractive man with a massively pockmarked face. He had a vigorous sex drive, fathering a child at seventy-eight by way of a maidservant, a calling of which he was inordinately fond. He kept a seraglio of three such women at one time, each one unaware of the others.)

Still, Wilkinson could and would free himself from these distractions, and by 1775, he and Watt, though of very different temperaments, had met and befriended each other, though it was a friendship based more on commerce than affection. Before long, their two inventions were, and to their mutual commercial benefit, commingled. Wilkinson’s “New Method of Casting and Boring Iron Guns or Cannon” was married to Watt’s “New Invented Method of Lessening the Consumption of Steam and Fuel in Fire-Engines.” It was a marriage, it turned out, of both convenience and necessity.

James Watt, a Scotsman renowned for being pessimistic in outlook, pedantic in manner, scrupulous in affect, and Calvinist in calling, was obsessed with getting his machinery as right as it could possibly be. While he was making and repairing and improving the scientific instruments in his workshop in Glasgow, he became well-nigh immured by his passion for exactitude, to much the same degree as had John Harrison in his clock-making workshop in Lincolnshire. Watt was quite familiar with the early dividing engines and screw thread cutters and lathes and other instruments that were then helping engineers take their first tentative steps toward machine perfection. He was accustomed to instruments that were carefully built and properly maintained, and that worked as they were intended to. He was mortally offended, then, when things went wrong, when inefficiencies were compounded, and when the monster iron engines he was now trying to build in the giant Boulton and Watt factory in Soho performed less well than the brass-and-glass models on which he had experimented back up in Scotland.

His first prototype large engines were spectacular behemoths: thirty feet tall, with a main steam cylinder four feet in diameter and six feet long, a coal-fired boiler, and a separate steam condenser, all massive. All the working parts were connected by a convoluted spiderweb of brass pipes and well-oiled valves and levers, with a spinning two-ball governor that prevented runaways. Above it all was a heavy wooden beam that rocked back and forth with metronomic regularity, turning a huge iron flywheel that in turn worked a pump that gushed water or compressed air or performed other tasks fifteen times a minute. Once at full power, the engine produced a concatenation of noise and heat and a juddering, thudding, stomach-churning intensity that somehow seemed an impossible consequence of merely heating water up to its natural boiling point.

Yet everywhere, perpetually enveloping his engine in a damp, hot, opaque gray fog, were billowing clouds of steam. It was this, this scorching miasma of invisibility, that incensed the scrupulous and pedantic James Watt. Try as he might, do as he could, steam always seemed to be leaking, and doing so not stealthily but in prodigious gushes, and most impudently of all, it was doing so from the engine’s enormous main cylinder.

He tried blocking the leak with all kinds of devices, things, and substances. The gap between the piston’s outer surface and the cylinder’s inner wall should, in theory, have been minimal, and more or less the same wherever it was measured. But because the cylinders were made of iron sheets hammered and forged into a circle, and their edges then sealed together, the gap actually varied enormously from place to place. In some places, piston and cylinder touched, causing friction and wear. In other places, as much as half an inch separated them, and each injection of steam was followed by an immediate eruption from the gap. This is where the blocking came in: Watt tried tucking in pieces of linseed oil–soaked leather; stuffing the gap with a paste made from soaked paper and flour; hammering in corkboard shims, pieces of rubber, even dollops of half-dried horse dung. A solution of sorts came when he decided to wrap the piston with a rope and tighten what he called a “junk ring” around the compressible rope.

Then, by the purest accident, John Wilkinson, in Bersham, asked for an engine to be built for him, to act as a bellows for one of his iron forges—and in an instant, he saw and recognized Watt’s steam-leaking problem, and in an equal instant, he knew he had the solution: he would apply his cannon-boring technique to the making of cylinders for steam engines.

So, without taking the precautionary step of filing a new patent for this entirely new application of his method, he proceeded to do with the Watt cylinders exactly what he had done with the naval guns. He had Watt’s workmen haul a solid iron cylinder blank the seventy miles across to Bersham. He then strapped the blank (in this case, for the very engine that he, as customer, eventually wanted, so six feet long and thirty-eight inches in diameter) onto a firmly fixed stage, and then secured it with heavy chains to make certain it did not move by so much as a fraction of an inch. He then fashioned a massive cutting tool of ultrahard iron that was three feet across (which should in theory have produced a cut that left a thirty-eight-inch-diameter cylinder with one-inch-thick walls) and bolted it securely to the end of a stiff iron rod eight feet long. This he supported at both ends and mounted onto a heavy iron sleigh that could be ratcheted slowly and steadily into the huge iron workpiece.

As soon as he was ready to begin working the piece, he directed, through a hose, a water-and-vegetable-oil mixture both to cool the thrashing metals and to wash away any fragments of cut iron; opened the water valve for the millrace and wheel that would set the rod and its cutting tool turning; and slowly and steadily, notch by notch by notch, set the rod moving forward until its cutting edge began chewing away at the face of the iron billet.

Читать дальше