William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2018

First published in the United States by McGraw-Hill in 1968

Copyright © 1968 by Edward Abbey, renewed 1996 by Clarke Abbey

Introduction copyright © Robert Macfarlane 2018

The Estate of Edward Abbey on behalf of the Author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

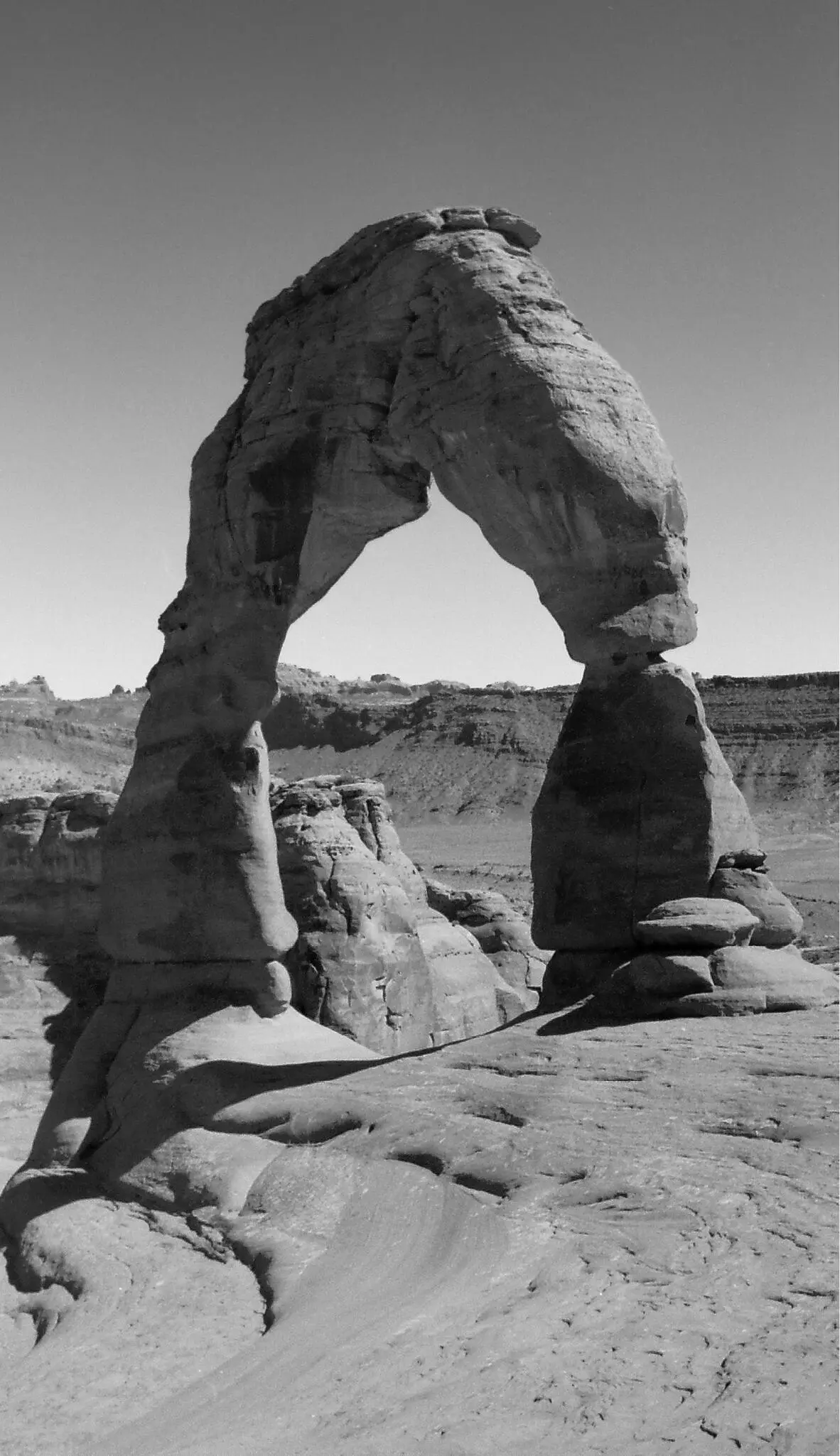

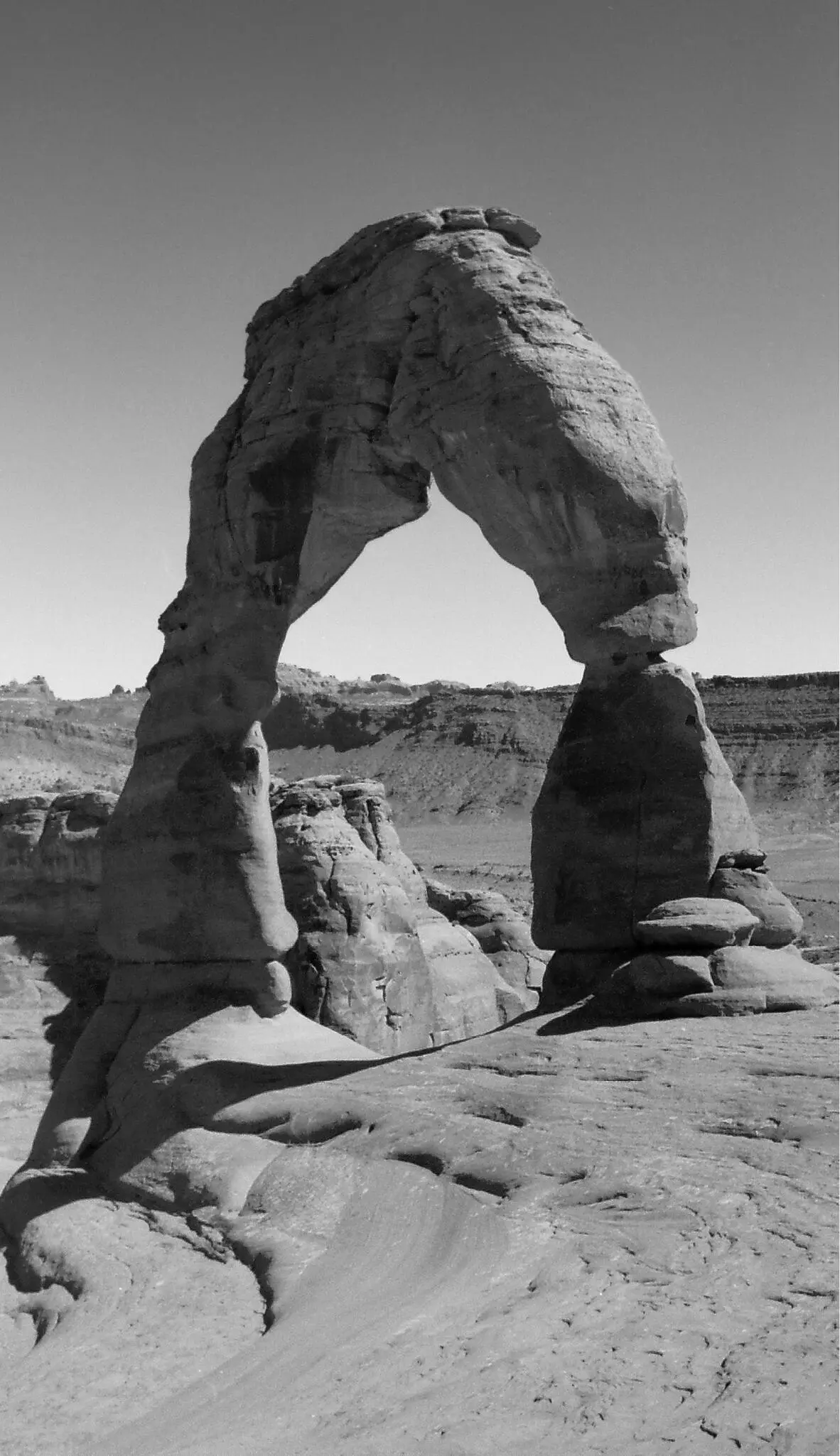

Frontispiece image © Wikimedia Commons/Nikater (2002)

Cover design by Jo Walker

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008283339

Ebook Edition © May 2018 ISBN: 9780008283322

Version: 2020-07-10

for Josh and Aaron

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Frontispiece

Introduction by Robert Macfarlane

Author’s Introduction

Epigraph

The First Morning

Solitaire

The Serpents of Paradise

Cliffrose and Bayonets

Polemic: Industrial Tourism and the National Parks

Rocks

Cowboys and Indians

Cowboys and Indians Part II

Water

The Heat of Noon: Rock and Tree and Cloud

The Moon-Eyed Horse

Down the River

Havasu

The Dead Man at Grandview Point

Tukuhnikivats, the Island in the Desert

Episodes and Visions

Terra Incognita: Into The Maze

Bedrock and Paradox

About the Author

About the Publisher

Introduction by Robert Macfarlane

Midway through this magnificent, maddening, abrasive, lyrical, lackadaisical kick-ass manifesto and dream-vision of a book, Edward Abbey describes climbing a switchback trail up from the banks of the Colorado to the high rock desert through which the river has cut its vast course. The trail is steep, the day hot and Abbey becomes so thirsty that he sucks damp sand in an attempt to extract its moisture. Nevertheless, he persists in his ascent – and at last emerges on the surface of a rolling plain of cross-bedded sandstone, where he is rewarded with the view for which he has been hoping. To the north-west he can see the island-mesa of the Kaiparowits Plateau and the descending levels of Grand Staircase-Escalante; away to his east are the salmon-pink buttes and hidden canyons of Bears Ears.

Abbey revels in what is concealed as well as what is revealed: he walks out to an isolated point, realises he can see no evidence of human presence bar his own sweating body, and stands there – listening to the immense silence, watching the ‘heat waves rising from the naked rock’. It is one of the many scenes in the book where Abbey ritually performs his definition of desert wilderness for his readers: a place that is defined by an utterness of matter, a deep-time vastness of space and earth-history; a place that humbles the human presence, and that should be left – in the (gendered) phrasing of the US Wilderness Act of 1964 – as ‘an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammelled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain’.

I write this essay fifty years since the first publication of Desert Solitaire , and I write it in a month when parts of the landscape that Abbey surveyed from that rimrock above the Colorado stand imperilled by the legislative actions of Donald Trump. In December 2017, Trump announced his intention to dramatically shrink the extent of two ‘National Monuments’ in the state of Utah: Grand Staircase-Escalante, which he reduced by almost half of its former extent, and Bears Ears, cut by 84 per cent. This reduction of two million acres of public land – which came into force on 2 February 2018 – is the biggest rollback of federal land protection in the history of the United States, and a centrepiece of the Trump administration’s broader assault on both conservation as idea and practice, and public land preservation specifically. One of the explicit intentions of the rollback is to open up both areas to the extractive industries (for coal and uranium in particular); as such it symbolically furthers Trump’s alignment with white working-class – especially mining and ranching – communities.

Announcing the shrinkage of Bears Ears in San Juan County in December, Trump both stoked and spoke to what Jedediah Purdy has called a ‘public-lands populism’; that is, a populism which ‘favors local, motorized and extractive uses of [western] public lands over federal policy-making, non-motorized recreation, and reservation for aesthetic or cultural purposes.’ In the view of this populism, all federal public lands – ‘National Monuments’, ‘National Parks’, ‘Wilderness Areas’ – in the western states represent ‘an illegal form of domestic colonialism’, an unjust land-grab begun by Ulysses S. Grant and Theodore Roosevelt over a century previously. Public-lands populists argue for the drastic reduction of federal control on grounds of historical illegitimacy, and the anomalously large extent of federal land in western states as compared to eastern and Midwestern states. This anti-regulatory, anti-federal narrative is itself tangled up in older western narratives about masculinity, liberty, self-reliance and the defence of sovereignty, all of which reach back into the earliest white incursions into these regions. Most problematically, proponents of contemporary ‘public-lands populism’, as Purdy has shown, have often sought to ‘de-legitimate the Native American presence in the West’, casting pro-preservation movements as a conspiracy of ‘green’ (environmentalist) and ‘brown’ (Native American) groups.

Since Trump declared the rollback in December, I have been considering what Abbey’s response would be to the proposals. It’s tempting just to quote Hayduke, the hell-raiser hero of Abbey’s cult novel The Monkey Wrench Gang (1975): ‘My job is to save the fucking wilderness,’ declares Hayduke unambiguously, ‘I don’t know anything else worth saving.’ Hayduke would, certainly, have poured sand in the fuel-tanks of mining machines and waged eco-guerrilla war on the infrastructure of incursion. But Hayduke is not Abbey and Desert Solitaire , Abbey’s fullest exploration of the ideas of wilderness, is a book from which it can be surprisingly hard to extract hard-and-fast positions, built as it is – in Abbey’s own phrase – on both ‘paradox and bedrock’.

Abbey pledges his allegiance above all to land, sandstone and the more-than-human world. ‘Long live diversity, long live the earth’ is the rallying cry he raises early in the book. He is unwaveringly against the development of wild land either for resource exploitation or for what he contemptuously calls ‘Industrial Tourism’. These positions form his bedrock. His paradoxes, though, are numerous. He despises motor vehicles, except when he is driving one. He celebrates personal liberty but also wishes to ‘lose’ his sense of self in the desert. He is an eco-centric misanthropist but also a localist whose sympathy lies most with blue-collar workers, including miners. He is suspicious of the federal state and a keen supporter of the Second Amendment. He contradicts himself repeatedly and with relish: ‘I’m a humanist: I’d rather kill a man than a snake.’ Doctrinally, he might be said to lie somewhere between Bakunin, Ammon Bundy and David Attenborough. But as Emerson observed, ‘consistency is the hobgoblin of tiny minds’. Abbey’s mind was expanded by the desert lands in which he took his stand, and his compellingly uncategorizable book is fully hobgoblin-free.

Читать дальше