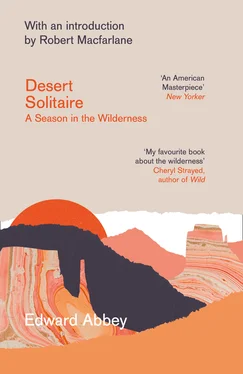

There are, unmistakably, aspects of Abbey’s book that make very uncomfortable reading today – and that should have made uncomfortable reading half a century ago. He is brazenly ableist and casually sexist. His desert is almost wholly a man’s desert. His adventures are undertaken exclusively with men. When women do feature, they are present as the wives of prospectors or park rangers, given passing mention at best; or they exist as problematic metaphors: the cliff-rose is ‘gay and sweet as a pretty girl’; after desert rain, a flower blooms ‘suddenly and gloriously, like a maiden’. Sentences describing the Navajo as ‘the Negroes of the Southwest – red black men’ who, ‘like their cousins in the big cities … turn for solace, quite naturally, to alcohol and drugs’, are unacceptable in ways that do not need unpacking.

It’s tempting to excuse these prejudices as subsets of an encompassing misanthropy, but that won’t do. Better to call him out on them – but also to note that Abbey himself hates haters, and that none of his prejudices is a simple case of rank bias. One of the four eco-terrorist heroes of The Monkey Wrench Gang is a formidable revolutionary feminist (though her portrayal is satirical as well as admiring), and it is obvious that, despite his intermittently objectionable language, Abbey’s respect for Native Americans is considerable. He suggests that much of western science has been anticipated by indigenous cultural knowledge, and commends the sophistication of the desert art and architecture of both the Navajo and the Anasazi, ‘the old people’. His anger flares at the way the Navajo have been cleared from desert lands and penned in reservations: ‘the Navajos are people , not personnel .’ And Abbey’s contempt for the nameless interlocutor who advances the wisdom of anti-Semitism at the book’s end is total and uncompromising.

In 2005 the Australian philosopher Glenn Albrecht coined the term ‘solastalgia’ to mean a ‘form of psychic or existential distress caused by environmental change’. Albrecht was studying the effects of long-term drought and large-scale mining activity on the well-being of communities in New South Wales, when he realized that no word existed to describe the unhappiness of people whose landscapes were being transformed about them. He proposed his new term to describe this distinctive kind of homesickness. Where the pain of nostalgia arises from moving away, the pain of solastalgia arises from staying put. Where the pain of nostalgia can be mitigated by return, the pain of solastalgia tends to be irreversible.

Solastalgia is not a malady specific to the present – we might think of John Clare as a solastalgic poet, witnessing the countryside of his native Northamptonshire disrupted by enclosure in the 1810s – but it has without doubt flourished recently. ‘A worldwide increase in ecosystem distress syndromes,’ wrote Albrecht, is ‘matched by a corresponding increase in human distress syndromes’. Solastalgia speaks of a modern uncanny, then, in which a familiar place is rendered unrecognizable by forces beyond individual control (climate change, global corporations): the home becomes suddenly unhomely around its inhabitants.

Desert Solitaire is, unmistakably, a work of solastalgia. Abbey’s ‘distress’ is channelled largely as anger, but what pains him is seeing the landscapes he loves transformed or destroyed by large-scale human intervention. The rafting trip he takes down Glen Canyon with Ralph Newcomb, shortly before that stretch of the Colorado was drowned by damming to form Lake Powell, is the most agonizedly solastalgic chapter in the book: ‘Glen Canyon was a living thing, irreplaceable,’ writes Abbey furiously, ‘which can never be recovered through any human agency.’ The account of his journey through this doomed place is superb for its range, its rage, its beauty and its comedy (the only map the two carry with them is a Texaco road map of the state of Utah; a detail which fascinatingly anticipates the ‘oil-company map’ carried by father and boy in Cormac McCarthy’s Anthropocene novel, The Road ). I still remember reading the Glen Canyon chapter for the first time fifteen years ago: jaw-dropped at the mysterious, off-planet beauty of the region through which the men raft on their ‘dream-like voyage’, gobsmacked at the loss of this mystery to the silt-sump of Lake Powell. That chapter, more than any other, advanced powerfully to me the idea of ‘irreplaceability’ as a conservation cornerstone: the proposition that certain landscapes are unique such that their loss cannot be ‘offset’ by some form of compensatory habitat creation.

Abbey’s identity politics have not weathered well, but his thinking about conservation and wilderness was in several ways ahead of its time. In his arguments for sentience and emotion on the part of creaturely life, he foresaw what is known as the ‘more-than-human turn’ across the social sciences and the humanities. In his repeated calls for the re-introduction of apex predators into ecosystems, he – like Aldo Leopold – prepared the way for later work on trophic cascades, and successful megafauna reintroduction programmes such as that of the wolf into Yellowstone, with all its consequent transformations of that area. Abbey’s disdain for sheep as ‘hooved locusts’ finds echoes in George Monbiot’s campaign for a British re-wilding movement to prevent the ‘sheep-wrecking’ of landscapes by overgrazing.

It is though, surely, in its defence of wilderness as a biophysical reality, with biodiversity as its core characteristic, that Abbey’s book holds most contemporary power. In the course of Desert Solitaire , he advances a number of familiar pro-wilderness arguments: that it is a ‘necessity of the human spirit’; that it is civilization’s accomplice rather than its antagonist; and that we need it available to us ‘whether or not we ever set foot in it, we need a refuge even though we may never need to go there’ (this last argument might be named the ‘geography of hope’ argument, after Wallace Stegner’s ringing phrase from his famous ‘Wilderness Letter’ of 1960).

These are, though, eventually anthropocentric arguments in favour of wildland preservation: philosophically, they all value ‘wilderness’ as resource. A spiritual resource, yes, rather than an ‘ecosystem service’ or a ‘standing reserve’ – but still a resource. Abbey proposes these in part to move past them, I think, towards a more radical ‘intrinsic value’ argument: that we need wilderness not for our sake, but for its own sake. ‘I am not opposed to mankind but only to man-centeredness,’ declares Abbey, ‘the opinion that the world exists solely for the sake of man.’ Echoing Thoreau, he holds it axiomatic that humanity ‘leave[s] some life pasturing freely where we never wander’.

In his memoir Grizzly Years (1990), Abbey’s friend and fellow outdoorsman Doug Peacock – allegedly the model for Hayduke in The Monkey Wrench Gang – recalls that the years when Abbey was writing Desert Solitaire were also the years when the idea of ‘wilderness’ came under attack. ‘After Vietnam I saw the world changing with amazing rapidity,’ remembered Peacock, ‘with a violent tempo that I had not noticed before 1968 … The entire concept of wilderness as a place beyond the constraints of culture and human society was itself up for grabs.’

The nature of that attack was in part industrial, and in part conceptual-intellectual. The conceptual attack on wilderness went, among other names, by that of ‘constructivism’. Constructivism broadly argues that the physical world is inaccessibly withdrawn from human encounter, that all knowledge is mediated through language and other forms of discourse, and therefore that meaning is invariably ‘assigned’ to phenomena, rather than arising from them. ‘Nature’ is no longer allowed its autonomy, becoming at most a hybrid and co-produced chimera, and ‘wilderness’ is an ideological spectre – a space of exclusion summoned into being by the activities of power.

Читать дальше