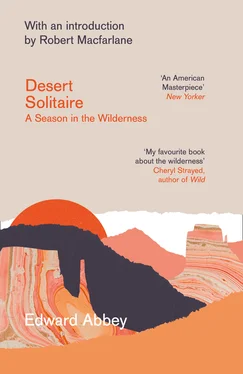

Like many great works of place-writing, Desert Solitaire has no plot. It describes – as the subtitle has it – a ‘season in the wilderness’ of Arches National Park. Like many great works of place-writing, Desert Solitaire also plays fast and loose with time, for into that single ‘season’ Abbey in fact collapses the stories and reflections of several years spent in the wider desert landscapes of the American south-west. What is presented as an almanac, running from April to September, is in fact more of an anthology of episodes from what he modestly describes as ‘God’s navel, Abbey’s country, the red wasteland.’

Within his calendrical structure, Abbey also dives, dolphin-like, between the continuous present and the archaic deep time of canyon and mountain. He lives variously in ‘the undivided, seamless days of those marvellous summers’, and in the immensities of earth-history, which have seen the roaming dunes of ancient deserts petrified into the slickrock of the desert states, itself in turn eroded by ice and wind into mesas, arches, bridges and arroyos. The alternations between these modes of time is one of the distinctive actions of Abbey’s book – the one vibrantly immediate, the other vertiginously ancient.

Desert Solitaire – like Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (1977) and Aldo Leopold’s Sand County Almanac (1949) – stands in clear relation with Henry David Thoreau’s founding work of American retreat literature, Walden (1854). Thoreau’s refuge was a log cabin on the shores of Walden Pond, Leopold’s was a shack in a meander of a Wisconsin river, Dillard’s a house in Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains – and Abbey’s is a tin house-trailer that is ‘cold as a tomb’ in spring and hot as a furnace in summer. Like Thoreau, Dillard and Leopold, Abbey undertakes his retreat as a means of philosophical sequestering: he goes to nature in order not just to think about nature but also to think with nature, and even more radically to be thought by nature. ‘The personification of nature is exactly the tendency I wish to suppress in myself, to eliminate for good,’ he says early on. The desert will rasp him free of anthropomorphism. Lying skin to skin with sandstone will give him fiercest focus on the otherness of matter.

In this respect, we should also understand Desert Solitaire as crookedly kindred with the practice of the early Christian Desert Fathers and Mothers, who removed themselves to remote desert places in order to maximise askesis and sharpen their faithfulness to its point. The ancient Greek word for this pure desert space was ‘paneremos’, from which arise our terms ‘eremitic’ and ‘hermit’. Abbey is a cranky kind of hermit, however – and he would have made a very poor monk. Though he flirts with the possibility of divinity a few times, he professes no belief in any kind of god (except, as he once jokes, ‘the smell of frying catfish’). His only theology is geology, really; his only spirituality is, he writes, ‘a hard and brutal mysticism in which the naked self merges with a non-human world and yet somehow still survives intact, individual, separate.’

Let us pause a little on the notion of that ‘hard and brutal mysticism’, for Abbey’s wrangles with this idea constitute one of the ongoing intellectual dramas of the book, and his accounts of it are riven with contradiction. How might the ‘naked self’ merge with matter yet remain ‘intact’? ‘Paradox and bedrock,’ Abbey would probably reply with a grin. He longs for an existence of pure noumena, and wants to use the spiky, scouring surfaces of the desert – ‘a realm beyond the human … spare, sparse, austere, utterly worthless’ – to abrade away anything ‘Kantian’, leaving only ‘the bare bones of existence’, ‘devoid of all humanly ascribed qualities’. Abbey calls this world-without-us the ‘antehuman’, and acknowledges that seeking it might ‘mea[n] risking everything human in myself’. Certainly, there is a brutality to any ontology that acknowledges only materialism. But there is an exhilaration, too, in exposing oneself to what he at one point calls the ‘monstrous’ inhumanity of ‘rock and cloud and sky and space’. ‘One must have a mind of winter,’ wrote Wallace Stevens in his great poem ‘The Snow Man’, in order not to anthropomorphise winter. Abbey seeks the impossible task of giving himself a mind of desert – of self-petrifying.

Abbey is not often compared to British writers, but at moments such as these he reminds me strongly of Nan Shepherd, who writes in The Living Mountain (1977) of following the ‘white waters’ of the Cairngorms back up to their source on the plateau, and by so doing placing herself at risk. ‘[T]his journey to the sources is not to be undertaken lightly,’ writes Nan. ‘One walks among elementals, and elementals are not governable.’ The Cairngorms are Nan’s desert; the running mountain water that ‘does nothing, absolutely nothing but be itself’ is Nan’s sandstone. I think also of J.A. Baker’s The Peregrine , a book published the year before Desert Solitaire , which shares a keen sense of species-shame with Abbey’s book, and a horror at the speed with which human activity is depredating the living world. Baker’s ‘season of hawk-hunting’ begins in autumn, ends in spring, and ‘winter glitters between like the arch of Orion’. Abbey’s ‘season in the wilderness’ begins in spring, ends in autumn, and between them the summer sun glitters off the sandstone arches. Both Baker and Abbey explicitly frame their books as elegies for landscapes that are ‘dying’: the pesticide-ravaged Essex countryside of Baker, and the development-menaced desert for Abbey. There is, too, in Abbey’s love of getting down on his belly to see what the world looks like to an ant or a lizard, something of the country-parson tradition of British natural-historical enquiry – though one can’t imagine Gilbert White or Francis Kilvert describing ants as ‘neurotic little pismires’.

Surely the oddest word in Desert Solitaire , though, is ‘lovely’. Abbey uses it repeatedly: ten times in the opening two chapters alone. ‘Instead of loneliness I feel loveliness,’ he writes. ‘The very names [of rocks] are lovely,’ he declares a few pages later, before incanting stone-types: ‘chalcedony, carnelian, jasper, chrysoprase and agate, onyx and sardonyx, flint [and] chert’ (if Abbey were a stone, he would surely be sardonyx). To hear the genteel term ‘lovely’ dropping from the lips of this beer-drinking, snake-shooting ‘desert rat’, nicknamed ‘Cactus Ed’ for his spikiness, is bewildering – as if he might suddenly also eat cucumber sandwiches with the crusts off and raise his little finger while sipping tea from porcelain cups.

But then voice is another aspect of this book’s inconsistencies: tonally, it can veer from barfly to baroque and back again in the course of a page. One of my favourite passages is where Abbey describes a pair of mating snakes as they ‘intertwine and separate, glide side by side in perfect congruence, turn like mirror images of each other and glide back again, wind and unwind again’. How sinuously Abbey doubles and echoes his own language in this self-entwining sentence! But another of my favourite passages is where he rages magnificently against ‘Industrial Tourism’ and the locust-like greed of the hordes who come to consume the desert through windshield and camera-lens: ‘Look here, I want to say, for godsake folks get out of them there machines, take off those fucking sunglasses and unpeel both eyeballs, look around; throw away those goddamned idiotic cameras! … and walk – walk – WALK upon our sweet and blessed land.’ The result of this mix of folksy fury and elaborate beauty is a book structured not unlike the ‘Spanish bayonet’ plant that Abbey admires at one point, a yucca with a ‘heavy cluster’ of gorgeous flowers, protected by an ‘untouchable dagger’s nest’ of leaves.

Читать дальше