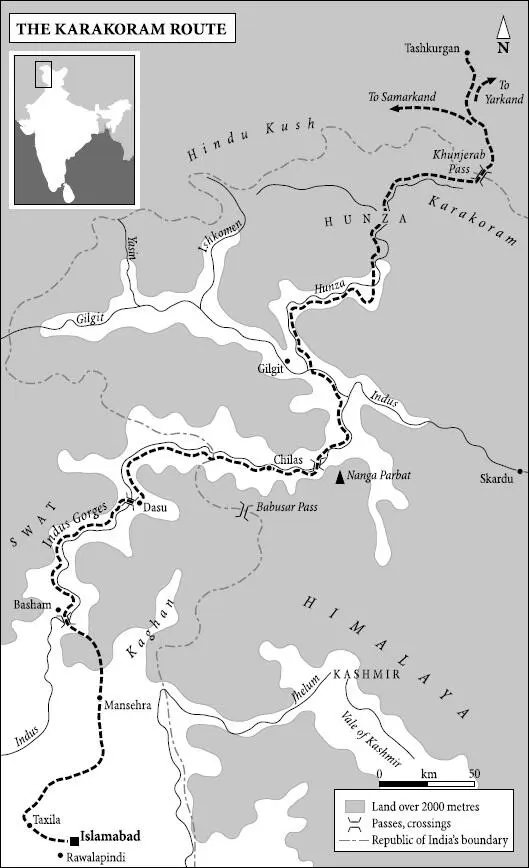

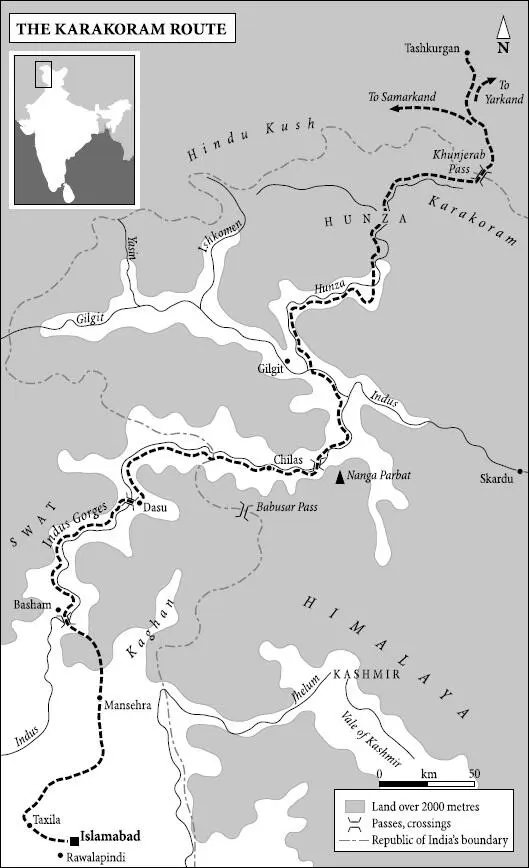

So the Karakoram Highway, though defying geography, can scarcely be said to have confounded history. In fact it faithfully follows what is now recognised as the preferred route of Buddhist missionaries carrying their teachings to Sinkiang and China.

It is also clear that the teachings in question were increasingly those of Mahayana Buddhism. At the Fourth Buddhist Council held under Kanishka’s auspices a long-simmering dispute within the sangha had led to schism. Those purists who adhered to the essentially ethical content of the Buddha’s teachings became the Hinayana school, while those who would elevate the Buddha and other potentially ‘enlightened ones’ to the status of deities deserving of worship, and so make of his teachings a conventional religion, became the Mahayana. The former persisted in not representing the Buddha as a human figure; in Hinayana art his presence is traditionally indicated merely by a footprint, a throne, a tree, an umbrella. But the Mahayana introduced the Buddha as icon, depicting the ‘enlightened one’ and a host of other Boddhisatvas, together with their female counterparts, in human form. The idea may have come from the imagery of Graeco-Roman gods introduced by the Bactrian Greeks and from the mainly Roman statuary which was evidently much treasured and traded thereafter. Certainly from this coincidence of Mahayanist demand and Mediterranean supply arose the distinctive style and motifs of Gandhara art.

The Kushana, controlling east – west trade in Bactria as well as vast territories in India, had wealth to lavish on both the new faith and the new art; they may even, like Gondophares, have imported western craftsmen like St Thomas. The style developed rapidly, influencing architecture and painting, and inspiring a narrative art based on Buddhist legend but using Graeco-Roman compositions and mannerisms. Exceptionally, the figure of the Buddha himself proved less susceptible to this ‘forum’ decorum; though draped in classical folds and endowed with a serene Grecian countenance, his posture, gestures and physical features conformed strictly to Indo-Buddhist iconography. Such was the Gandhara tradition, a curious synthesis of Kushana patronage, Graeco-Roman forms and Indian inspiration. In sculpture, stucco, engraving and painting, it was this synthesis which passed on up the Karakoram route, or round via Bamiyan and Bactria, to fill the monasteries along the Silk Route and provide the inspiration for later Buddhist art in China and beyond.

The Karakoram trail would be little trodden after the fourth century, when Buddhism in north-west India would be eclipsed by more intruders from central Asia, this time the Huns. Despite those ravages of time and nature, the Karakoram records have therefore remained comparatively undisturbed. Significantly, they reveal little about the route being used for trade. Chinese silks, in particular, were imported into India for re-export from India’s west coast ports to Egypt and Rome. If such caravans avoided the Karakoram route it was presumably because they found the gradients and the grazing of the Bactrian route more agreeable than the cliff-face ladders of Hunza and the landsliding slopes of the Indus gorges. Lacking commercial potential, the Karakoram route was quietly abandoned.

LOOKING OUTWARDS TO THE SEA

Elsewhere the exchange of ideas matched that of commodities stride for stride, stage for stage. In peninsular India – the region south of the Narmada river comprising the Deccan and the extreme south – the last centuries BC and the first AD witnessed those processes of urbanisation and state-formation which had taken place three centuries earlier in the Gangetic region. But here it was trade which stimulated the transition and trade routes which defined it, especially in the western Deccan (Maharashtra and adjacent regions) and in the extreme south (Tamil Nadu and Kerala). Something of that slow metamorphosis from pastoralism and subsistence agriculture to wet rice-cultivation and an agricultural surplus is also discernible. The construction of irrigation works in the south goes back to the second century BC and was accompanied by a demographic shift from upland settlements to the alluvial and easily watered soils of the deltas. ‘In the Chola country, watered by the Kaveri, it was said that the space in which an elephant could lie down produced enough rice to feed seven’ (people, presumably, rather than elephants). 10But here a surplus laboriously realised from agriculture, and then partially squandered on oblations designed to ensure its repetition, was second-best to the surplus on offer from the export of marine and forest produce (especially pearls and pepper) and the re-export of luxury items from further afield. Such options, not open to the Gangetic states, propelled the peninsula from Stone Age to statehood in record time.

Before the first century BC the southern extremity of the subcontinent scarcely features in India’s history. Today’s southern states – Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Kerala – correspond to the languages spoken in each, respectively Kannada, Telugu, Tamil and Malayalam. All belong to the Dravidian family, which is quite distinct from the Indo-Aryan whence Sanskrit and most of north India’s contemporary languages derive.

Dravidian-speakers are thought to have preceded Indo-Aryan-speakers in the subcontinent. It has yet to be proved that the Harappans’ language was some form of Dravidian, but the survival of a pocket of proto-Dravidian-speakers in Baluchistan, the Pakistan province which borders with Iran, does suggest that the language was in use west of the Indus and could have emanated from there. It also once enjoyed a wide currency in Gujarat and Maharashtra, though whether in the course of a ‘descent’ to the south, or an ‘ascent’ from it, is uncertain. By the mid-first millennium BC, it was certainly well established in the south, perhaps as a result of dissemination by Dravidian-speakers possessed of the horses and iron weaponry usually associated with the Sanskritic arya , or possibly very much earlier as the language of those responsible for the megalithic sites found in upland regions of the peninsular interior.

The four Dravidian languages must have developed from proto-Dravidian at an early stage since they were already distinct from one another in prehistoric times. Each, too, was already confined to the region represented by today’s states. In fact the continuity of such geo-linguistic entities is the outstanding feature of south Indian history. Here, unusually, definable linguistic units seem to predate the states into which they would become integrated.

Megasthenes in around 300 BC knew of the Pandya kingdom; then, as subsequently, it occupied ‘the portion of India which lies southward and extends to the sea’; and it had 365 villages, a not incidental number in that each was expected to supply the needs of the royal household for one day in the year. Ashoka was even better informed. In the Major Rock Edicts he lists his southern neighbours as the Cholas and Pandyas (respectively the northern and southern Tamil-speaking peoples), the Satiyaputras (whose identity is disputed), the Keralaputras (or the Malayalam-speakers of Kerala), and the people of Sri Lanka. Although none formed part of the Mauryan empire, all, according to the Beloved of the Gods, acknowledged the superiority of dhamma and had imitated the Ashokan provision of roadside shade trees and of medical care for men and animals.

Later the all-conquering Kharavela, king of Kalinga (Orissa), also noticed the southern kingdoms. In his one extant inscription he typically pretends to have defeated a confederacy of Tamil states and to have acquired a large quantity of pearls from the Pandyas. Pearls and shells, along with the fine cottons of Madurai, the Pandya capital, are also mentioned in the Arthasastra . There, in a discussion on how to maximise the state’s revenue, Kautilya’s mentor rashly suggests that north India’s most valuable trade is that with central Asia. The know-all brahman puts him right in no uncertain terms: the trade via the Daksinapatha (the ‘Southern Route’) is the more valuable and, besides, the route is very much safer. Thus trade with the south, albeit in prestige goods, was well-established in Mauryan times; and by way of the secure – and, no doubt, well-shaded – Daksinapatha prestigious ideas also travelled down the peninsula.

Читать дальше