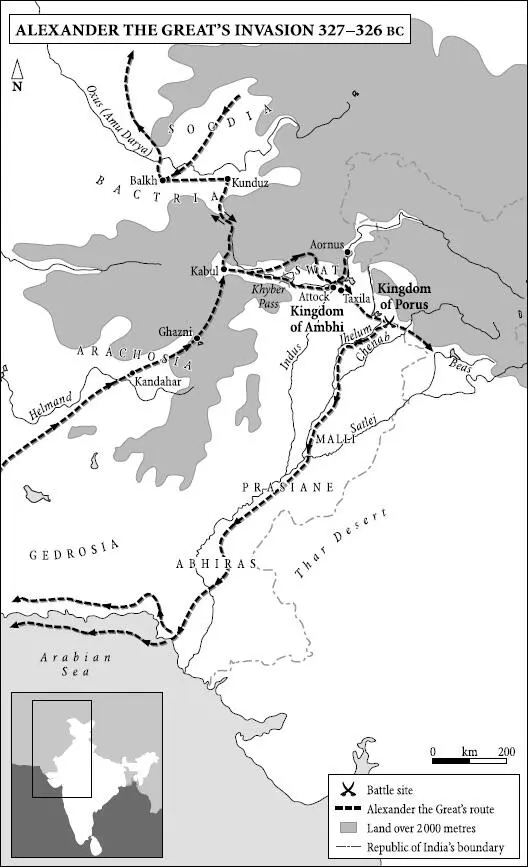

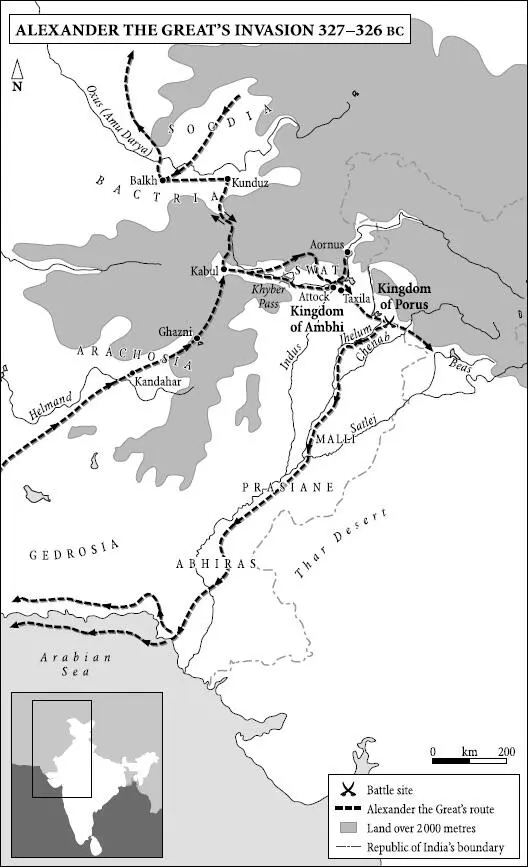

A city built on trade and scholarship with little in the way of natural defences stood no chance. Taxila had survived the Achaemenids, indeed was a part-Achaemenid city. It could manage the Greeks in the same way. When Alexander descended to the Indus he found thousands of cattle and sheep, as well as elephants and silver, awaiting him. Ambhi, with nought to gain by resistance except the annihilation of his illustrious city and the applause of a very remote posterity, was playing safe. Alexander confirmed him as his satrap and generously repaid his liberality.

At the time Taxilan territory extended modestly from the Indus to the Jhelum. Beyond, occupying the next sliver of the Panjab between the Jhelum and the Chenab, the kingdom of ‘Porus’ lay across the invaders’ line of march. In Greek as in Indian tradition, Porus is all that Ambhi is not. A giant of a man, proud, fearless and majestic, he may have owed his name to Paurava descent, the Pauravas being only slightly less distinguished than the Bharatas in the pecking order of Vedic clans. Alexander had summoned him, along with other local rulers, to meet him and render tribute. Porus welcomed a meeting, adding casually that an appropriate venue would be the field of battle.

As good as his word, and despite the fact that the monsoon had already broken, Porus massed his forces on the banks of the Jhelum. Normally the monsoon brought all campaigning in India to an end. Indian troops were ill-equipped to fight in the rain, and Porus probably trusted to the flooding Jhelum to halt the enemy. But Alexander, well used to river crossings, organised boats, duped the enemy as to his crossing place, and between torrential downpours gained the further bank. The battle that followed was anything but a formality. Porus’ chariots slithered uncontrollably in the mud and his archers could find no purchase for their massive bows, one end of which had to be planted in the ground. Yet the Indian forces, though outnumbered as more of the enemy crossed the river, fought valiantly. Abristle with spearsmen, the elephant corps trundled across the battlefield like towering bastions on the move. Their repeated charges drove all before them, the Greeks merely peppering them with missiles as they reformed. But Alexander now knew enough of elephants to bide his time. His tactical skills were unmatched, and his cavalry easily outmanoeuvred their rivals. As the battle wore on, the Indians found themselves penned into an ever smaller circumference. Enraged elephants now trampled friend and foe alike. Exhausted, ‘they then fell back like ships backing water, and merely kept trumpeting as they retreated with their face to the enemy’. With shields linked, the Macedonian phalanx then pressed in for the kill. ‘Upon this, all turned to flight wherever a gap could be found in the cordon of Alexander’s cavalry,’ according to the account compiled by Arrian.

Porus, wounded but still conspicuously fighting from the largest of the elephants, was captured. ‘How did he expect to be treated?’ asked Alexander. ‘As befits a king,’ he famously replied. To the Greeks it sounded, under the circumstances, like an extraordinarily noble and fearless request. Alexander responded magnanimously, reinstating him as king and subsequently augmenting his territories. But Porus’ words could as well have been those of Lord Krishna, whose advice to Arjuna in the Mahabharata made much the same point. Each must live according to his dharma ; it was the dharma of a ksatriya to fight and to embrace the consequences. Probably Porus was not boldly appealing to Alexander’s clemency, nor presuming on some brotherhood of sovereignty; he was simply stating his dharma .

After exceptionally elaborate celebrations, the Macedonians moved on, continuing east and south across the grain of the Panjab river system. The rains ended and the land blossomed. They crossed the Chenab, then the Ravi. Countless ‘cities’ capitulated, others, some evidently republican gana-sanghas , offered a short-lived resistance. Even to Alexander it was becoming apparent that ‘there was no end to the war as long as an enemy remained to be encountered’. Rumours of the vast forces commanded by the Nandas of Magadha (the ‘Gangaridae’ and ‘Prasii’ to the Greeks) now began to infiltrate the ranks. ‘This information only whetted Alexander’s eagerness to advance further,’ says Arrian. The Ganga, mightier even than the Indus, must surely carry them to the ocean at the end of the world. Its plain was reported as exceedingly fertile, its peoples excellent farmers as well as doughty fighters, and its governments civilised and well organised. Alexander sniffed the prospect of an even more glorious dominion.

But his men were unimpressed. They crossed what is now the frontier between Pakistan and India somewhere in the vicinity of Lahore. Then, near Amritsar, they reached the Beas, fourth of the Panj-ab , the ‘five rivers’. In this weird and interminable land where the clothes were all white and the complexions all black, it was as good a place as any for a showdown with their commander.

Alexander sensed the mood of mutiny. In a lengthy appeal to his commanders he invoked their past loyalty and stressed the consequences of retreat. Extricating themselves would be difficult. Were the tide of conquests now to ebb, they would find the sands sucked from under their feet. New friends would review their allegiance and old enemies would take their chance. Trumpeting an empty defiance, the Greeks would find themselves backing away amidst a shower of missiles just like Porus’ exhausted elephants.

But to men who had been on the march for eight years, such arguments had little appeal. They had bathed in the Tigris and the Indus, the Nile and the Euphrates, the Oxus and the Jaxartes. Across desert, mountain, steppe and field they had trudged for over twenty-five thousand kilometres. Of victory, booty, glory and novelty they had had their fill. With respect and real affection, they listened to their leader, moved but unpersuaded.

Alexander withdrew to his tent like his hero Achilles. A three-day sulk made no greater impression on the men’s resolve, while a sacrifice for safe passage of the river produced only adverse omens. In the end Alexander had no choice but to announce a withdrawal. The banks of the Beas erupted with cheers of relief; many wept but all rejoiced. As Arrian noted, Alexander was vanquished only once – and that by his own men.

To round off his conquests, complete his explorations, and disguise his failure, Alexander opted to return by sailing down the Jhelum and the Indus to the ocean. Ships were readied and he sailed in late 326 BC. The voyage downriver took six months. Stern opposition came from numerous riverine peoples, some of whom have been tentatively identified, and from sizeable townships which clearly included well established brahman communities. Some of these townships no doubt occupied sites beneath which the Harappan cities had already lain, cocooned in alluvial oblivion, for 1500 years.

In an engagement with the ‘Malloi’ Alexander himself was seriously wounded. An arrow struck him in the chest and may have punctured his lung. He barely recovered. The wisdom of forgoing a contest with the Nandas’ multitudinous cohorts was amply demonstrated; so were the dangers of withdrawal. With few regrets, in September 325 BC the fleet sailed out of the Indus into the Arabian Sea. Meanwhile Alexander led the rest of his men west on what proved to be, for many, a death-march to Babylon along the desert coast of Gedrosia (Makran). There was still some talk of returning to India, of resuming the march with fresh troops, and of consummating the ultimate conquest. But other appetites proved Alexander’s undoing. Within two years he died from hepatoma following a massive banquet in Babylon.

Читать дальше