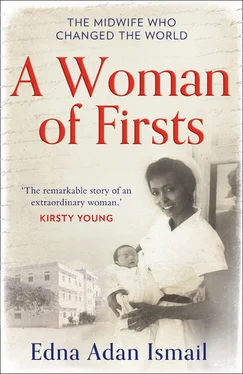

If I were to fulfil that wish then what better gift could I give him than his own hospital? How I would achieve it, I didn’t know. What money I’d use to make it happen, I had no idea. Neither of us knew that political turmoil and civil war would soon devastate our country. We could never have foreseen the suffering. At twelve years old, I only knew that one day my father’s name would be placed for all to see on a large white hospital built in his honour. I didn’t even tell him of my secret plan. Yet the idea sprang into my young head so clear and bright and certain. It lodged in my subconscious like tumbleweed caught on a thorn, and that’s where it remained for more than fifty years until I finally had the time and resources to do something about it. This is the story of how I made that happen, against insurmountable odds.

Hargeisa, British Somaliland Protectorate, 1937

Seven days after I was born at 9 p.m. on 8 September 1937 following a long and difficult delivery, my father gave me the name ‘Shukri’, which means thanks. This was because I was considered something of a miracle after two years of my mother’s infertility.

The only reason I know the date of my birth is because I was born in a hospital in Hargeisa, unlike the majority of Somalilanders. We didn’t mark birthdays in the same way as people in the West because we didn’t then have a written language, very few people could read, and no one knew what a calendar was. Many my age don’t know when they were born and say simply ‘the time of bad floods’, or ‘the month before the long drought’. Age was counted by the rainy seasons, of which there are two, so a child who has seen two rains would be described as two years old when they were really only one.

I was a big, healthy baby although I carry two scars on my head from the forceps used by the English obstetrician who delivered me. Perhaps the miracle of my survival in a country where infant mortality is still the fourth highest in the world is the reason I became such a headstrong child and a stubborn adult – to which many will attest. With ninety-four in every 1,000 babies dying at birth in Somaliland (compared with four or five in the UK and the US), it is customary for newborns never to be named until they are a week old for fear their parents become too emotionally attached.

At my naming ceremony on 15 September, my mother Marian, a Somali who’d been raised a Catholic, called me Edna in honour of a Greek girlfriend who insisted that if I was a girl then I should take her name. It was a moniker Dad never once used. My arrival ended what my mother feared was a curse against her ever since she’d married my father two years earlier. Many of those who liked my father disapproved of his marriage and believed that he should have chosen a Muslim wife. This view only gained currency when Mum hadn’t yet borne him a child, as, in our culture, it is normal for a wife to conceive straight away. If she doesn’t it is usually blamed on ‘the evil eye’ or some other bad spirit and Allah is prayed to, so when Mum finally became pregnant with me the evil eye was considered to have blinked.

My father was over six feet tall, charismatic, generous, fluent in several languages and the best doctor and communicator I’ve ever met. To him, teaching people about healthcare was not only a duty but also a pleasure, and he threw his heart and soul into educating anyone he came across. One of his favourite expressions was, ‘If you cannot do it with your heart then your hands will never learn to do it.’

His own father, Ismail Guleed, was something of a legend in Somaliland. A successful, silver-haired merchant from the noble Arap Isaaq clan of nomadic warriors and camel herders, he was known as Ismail Gaado Cadde, which means White Chest. This referred to the white hair on his chest that spilled over his tunic.

Wealth in my country is measured in camels – a female and her calf can cost £1,000 in today’s terms – and my grandfather exported large herds of them. Independently wealthy, he hired traditional dhow boats to carry goods destined for Ethiopia and service his lucrative contract to supply livestock, firewood and ghee to the British garrison in the Aden Colony, sixty kilometres across the Gulf of Aden – the gateway to the Red Sea.

Grandfather Ismail naturally expected that his two sons – my uncle Mohamed and my father Adan, born in 1906 – would help run his business. He and his wife Baada had moved to Aden once their sons were of school age specifically so that they could be educated at St Joseph’s, a Roman Catholic Mission School, the only place in the region where they could learn to read and write in English. Little did he know that my uncle Mohamed would jump on a ship bound for the Indian Ocean aged sixteen to become a merchant seaman for the rest of his life, while my father would choose medicine. Sadly, Grandfather died in his early sixties, so I never knew him. After his death my father tried to keep the family business going but it became too difficult to manage on top of his medical duties.

I sorely wished I’d asked Dad what made him decide to study medicine because it was truly a vocation for him and something he dedicated his whole life to. Perhaps there was an incident that inspired him. As far as I’m aware, he was never ill, but he did have multiple scars on his legs from playing football and hockey so perhaps that was how he encountered the miracle of medicine.

***

My earliest childhood memories are of my grandmothers’ faces, fleeting images of their beaming smiles. These women were perhaps the most influential in my immediate family, although the men in our vast extended clan traditionally exerted the most control. As another Somali girl child my infancy was rather uneventful, apart from the day I disappeared as a baby. Mum left me sleeping on her bed with cushions stacked all around me to prevent me from falling off, then went to the outdoor kitchen at the back of our house to prepare lunch – probably sabaya flatbreads with some curry or beans and rice. Our single-storey detached house had two bedrooms as well as a living/dining room. There was no flushing toilet, just a shaded pit latrine in the yard, and my mother, the cook and a maid heated water over firewood laid on stones and cooked meat over a charcoal burner made from oil drums.

When my mother came to check on me a little while later, she found me missing and the pillows undisturbed. Perplexed, she thought my father must have come home from the hospital in his break and carried me outside. When she couldn’t find us in the yard, she believed he’d taken me back to his hospital without telling her. In a country with regular epidemics of smallpox and other diseases she, like most Somali women of her generation, had a terrible fear of taking a healthy child to a place full of sick people so – furious – she hurried to the hospital only to find Dad alone. He was just as surprised to see her because she never visited unless for a medical emergency. Mum immediately started wailing that I had been stolen. They hurried back home and they, the servants, our neighbours, and eventually the police looked frantically for me and traces of my ‘kidnapper’. Amidst the hubbub, no one thought to look under our dining room table to which I had crawled beneath the tablecloth to resume my nap. Once I was discovered my mother never lived down the embarrassment and Dad would often tell me how lucky I was that I wasn’t chained to the bed after that.

I was only two when the Italians declared war on the Allies in June 1940 and in August invaded British Somaliland and Ethiopia. I have no recollection of the events of the Second World War or the impact upon our family. Nor do I recall the events just before that when my mother’s next child, my unnamed infant sister, died a few minutes after birth following another harrowing forceps delivery. Mum was frail and still recovering when the British declared that all the wives and children of civil servants should evacuate to a small fishing village on the Gulf of Aden. From there we’d board a British naval destroyer for Aden.

Читать дальше