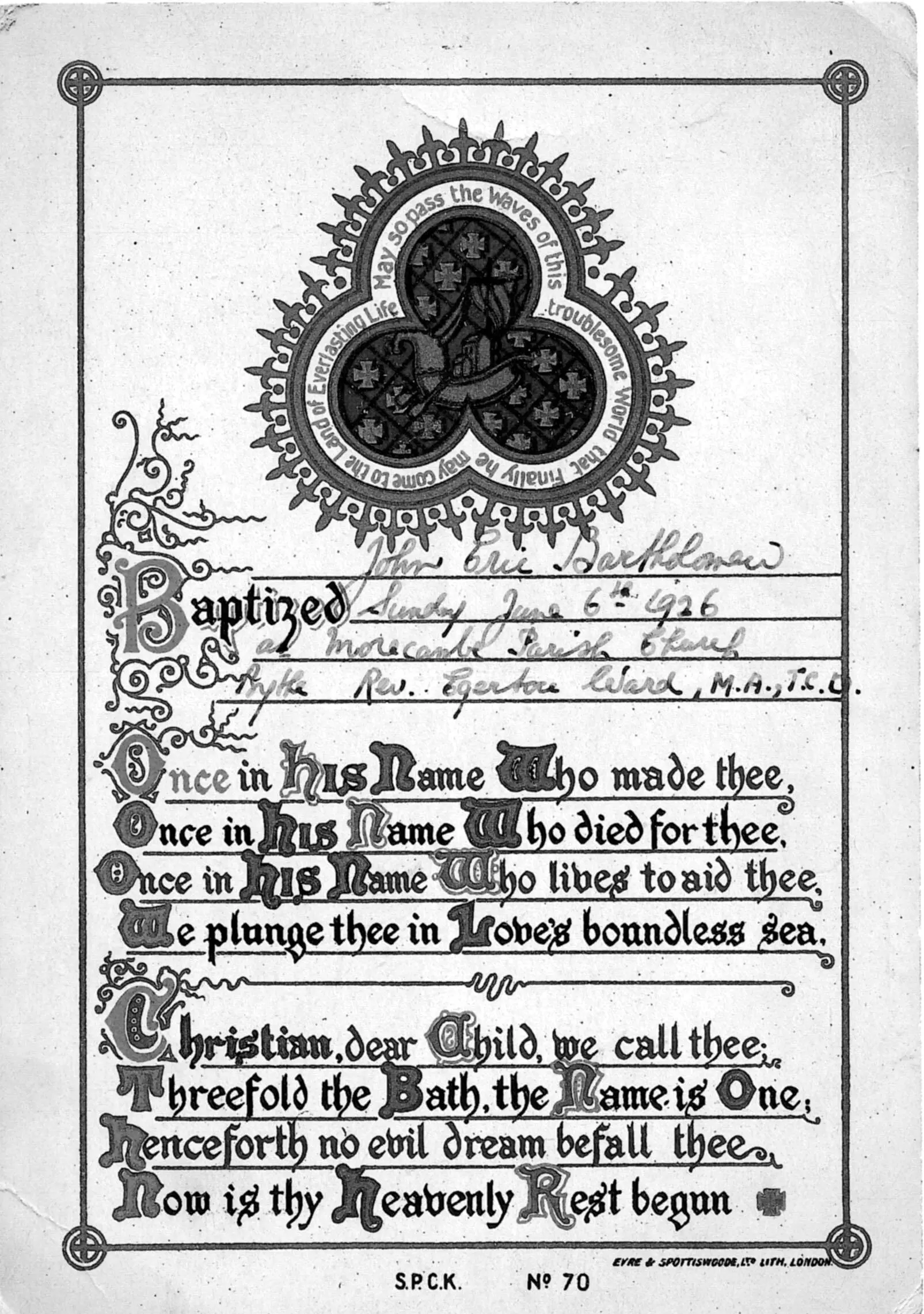

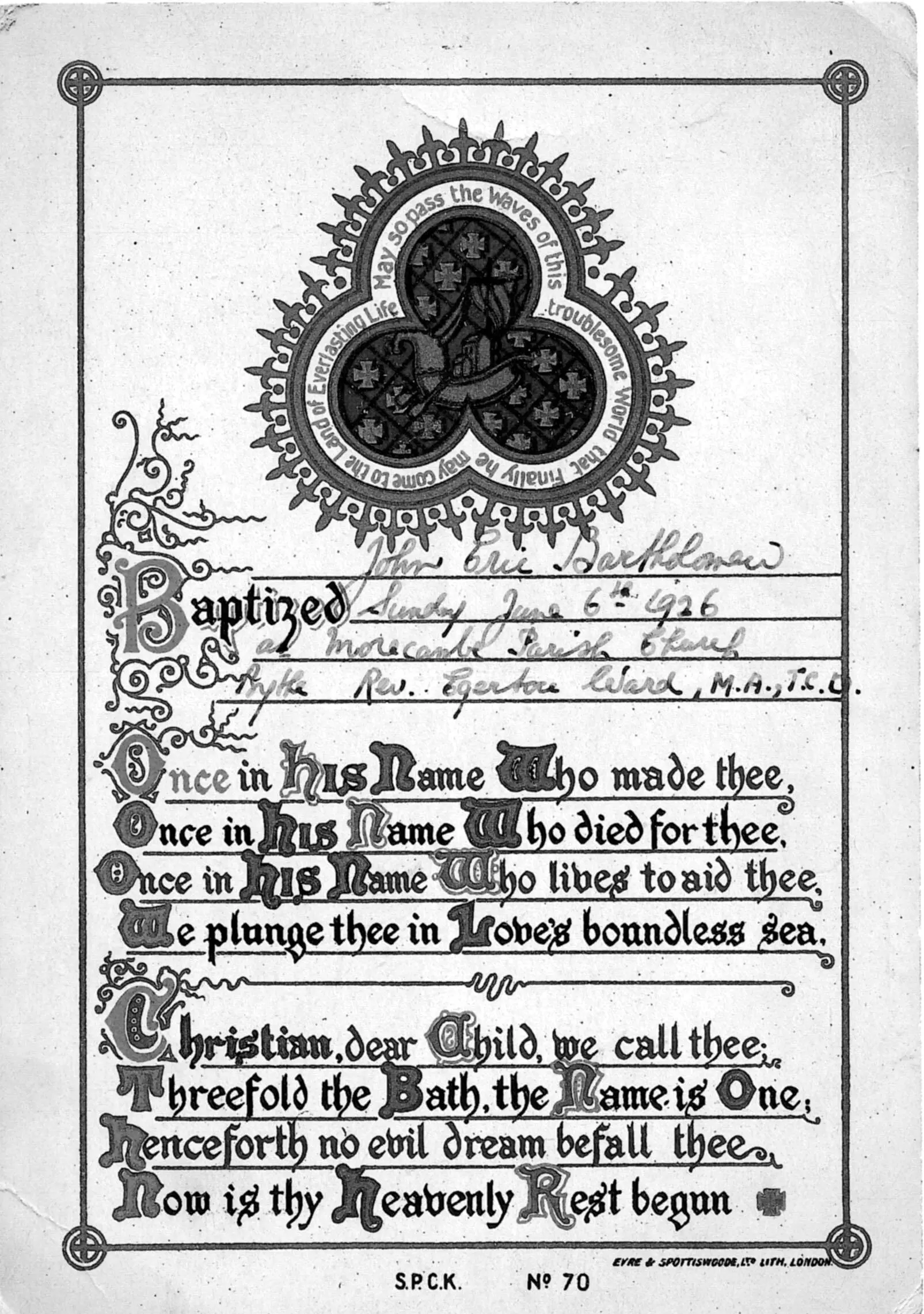

EVEN THE CIRCUMSTANCES of Eric’s birth were vaguely comical. He was born John Eric Bartholomew on 14 May 1926, at 42 Buxton Road, Morecambe, but his mother and father actually lived a few doors away. They’d had to move in with neighbours while their own house was repaired. Once their proper home was patched up they moved back in again, but within a year it had become unfit for human habitation. Eric’s earliest memory was the ceiling collapsing. It must have been pretty awful at the time, of course, especially for his hard pressed parents, but looking back it sounds like a slapstick scene from one of his favourite silent films.

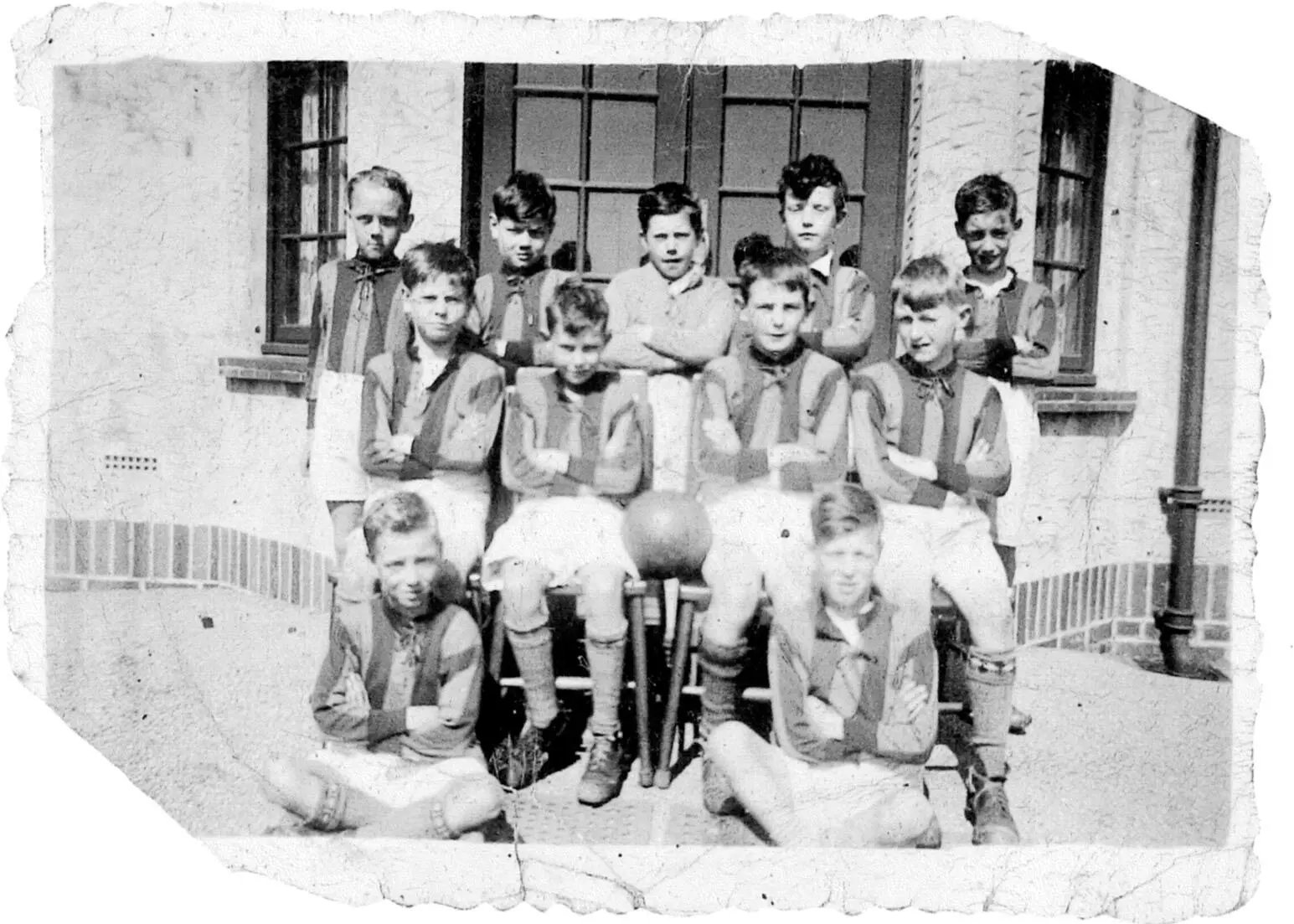

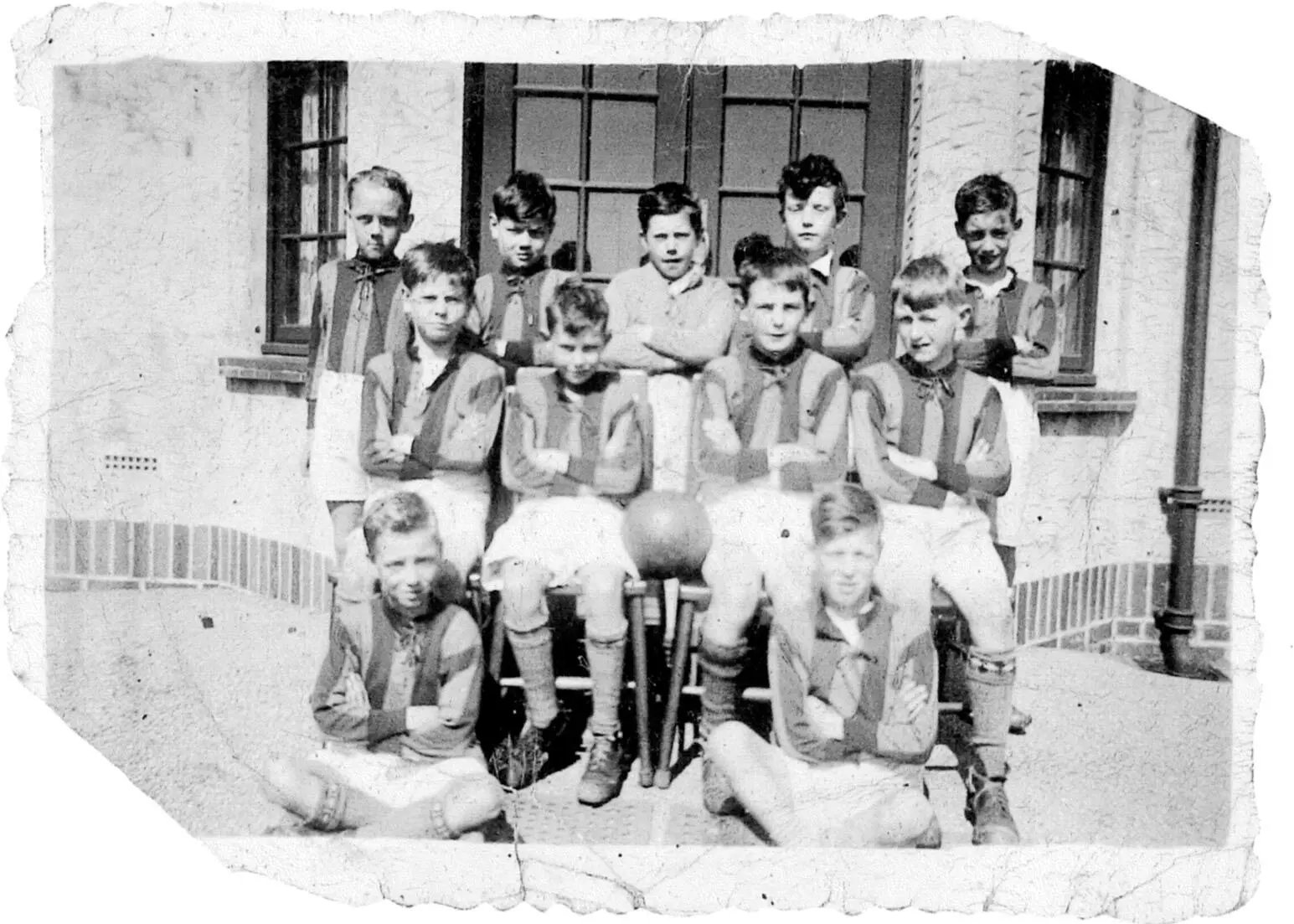

Although he was already taking dancing lessons, and entering local talent contests, Eric’s boyhood dream was to become a professional footballer. And unlike most of his teammates, this was no idle fantasy. A fine left winger, he attracted the interest of several league scouts, but his father, who’d suffered a crippling injury as an amateur, advised him against it. In those days there was no money in it, and your career was over by the time you were thirty, so Eric subsequently decided it would be a better bet to settle for show business instead.

Buxton Road is the sort of terraced street you see in Lowry paintings, full of kids playing football, but by the time Eric was old enough to kick a ball his parents had moved into a new council house, 43 Christie Avenue, behind the main stand of Morecambe Football Club, where Eric lived until he left home. By modern standards, Eric’s childhood home in Christie Avenue looks pretty Spartan, but back in the 1920s it was a proletarian dream come true. It had three bedrooms, its own front door, and best of all, its own garden – still a rarity in those days, especially for folk of the Bartholomew’s humble social standing. This garden was the summit of Eric’s father’s expectations. Luckily for Eric, and the future of British comedy, his mother’s aspirations weren’t confined to this pleasant but unprepossessing patch of lawn.

Eric’s parents both came from similar working class backgrounds, but their personalities could hardly have been less alike. Orphaned at an early age, his mother Sadie was a sharp and restless woman who was always striving to better herself – and her family. His father George, on the other hand, was one of those rare individuals who are utterly contented with their lot. One of life’s plodders, he toiled away serenely as a council labourer from the day he left school until the day he retired, entirely satisfied with the modest cards he’d been dealt. Like the soldier in the wartime song, he really did whistle while he worked. Despite their contrasting attitudes – or perhaps, in part, because of them – George and Sadie got along very well. In their very different ways, they each nurtured Eric, and he formed a close bond with both of them that would sustain him throughout his life. Eric’s incredible career was a testament to his driven (and hard driving) mother, but his happy go lucky stage persona was a tribute to his easy going dad. ‘George was a character,’ says his grandson, Gary. ‘I remember giving him some aftershave for Christmas, and him ringing up and saying it was the worst sherry he’d ever drunk.’ It sounds like a classic Eric Morecambe one liner.

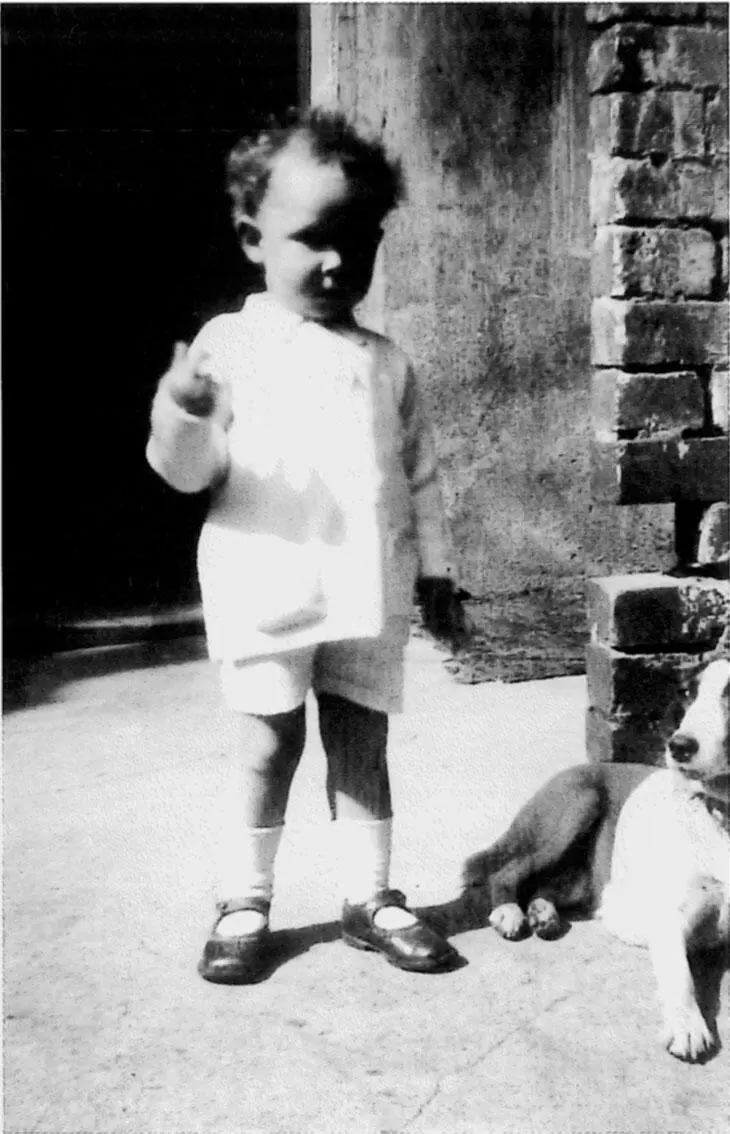

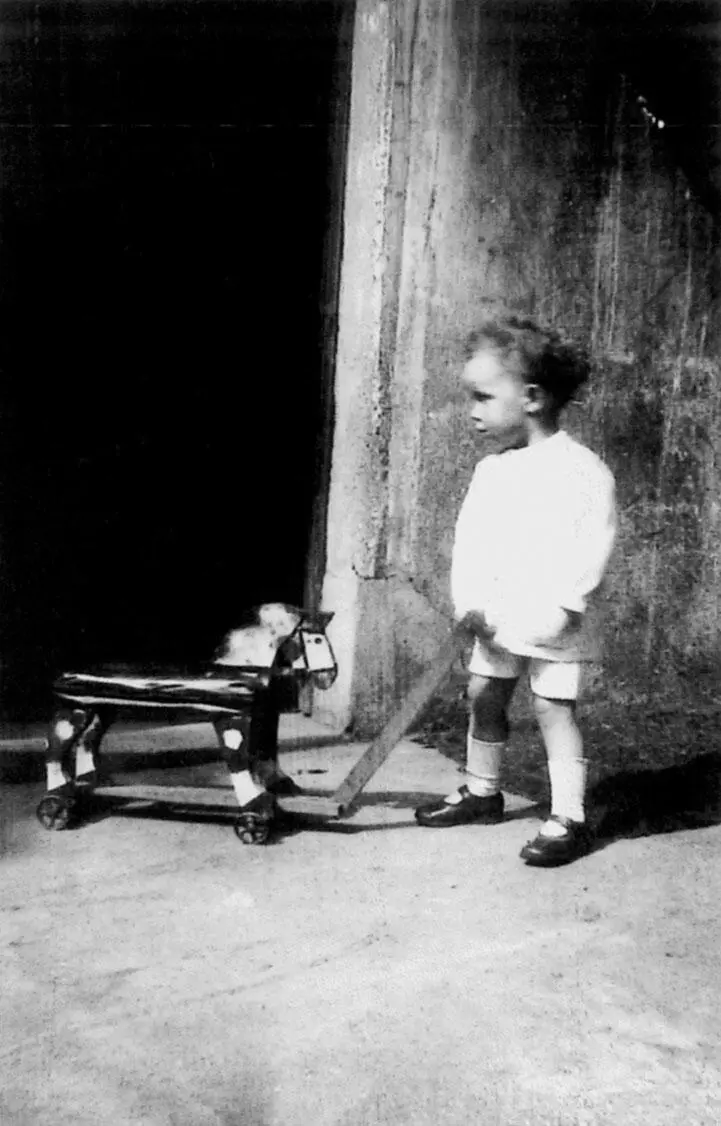

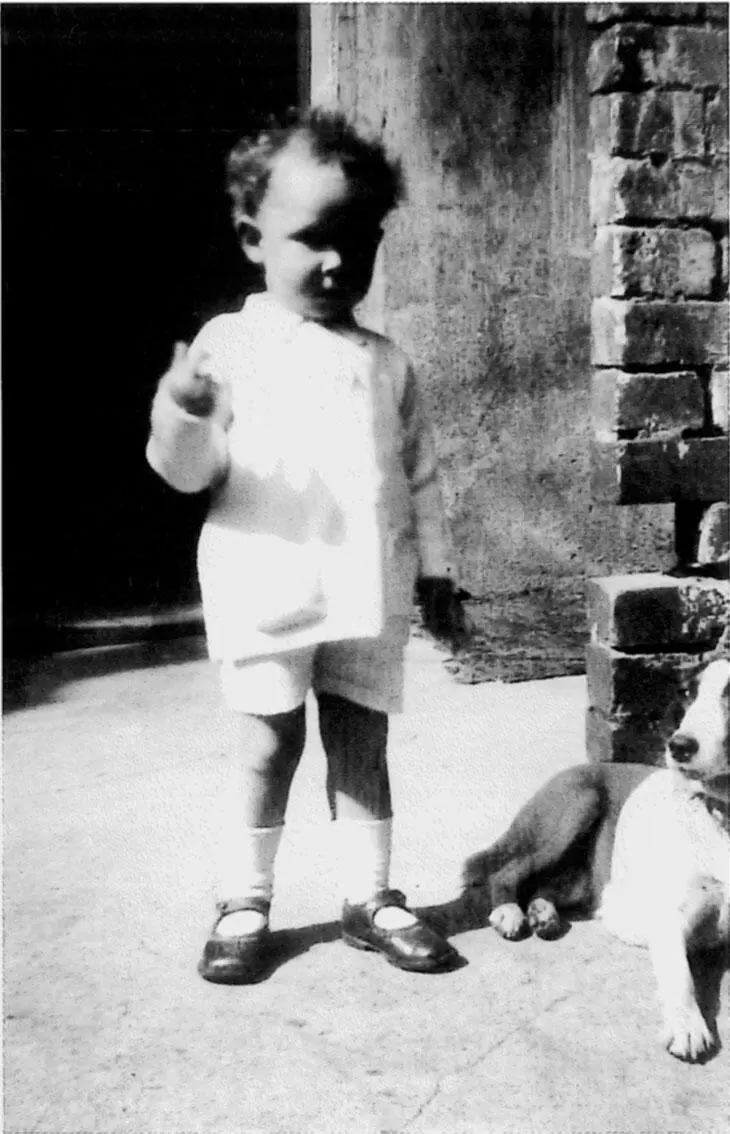

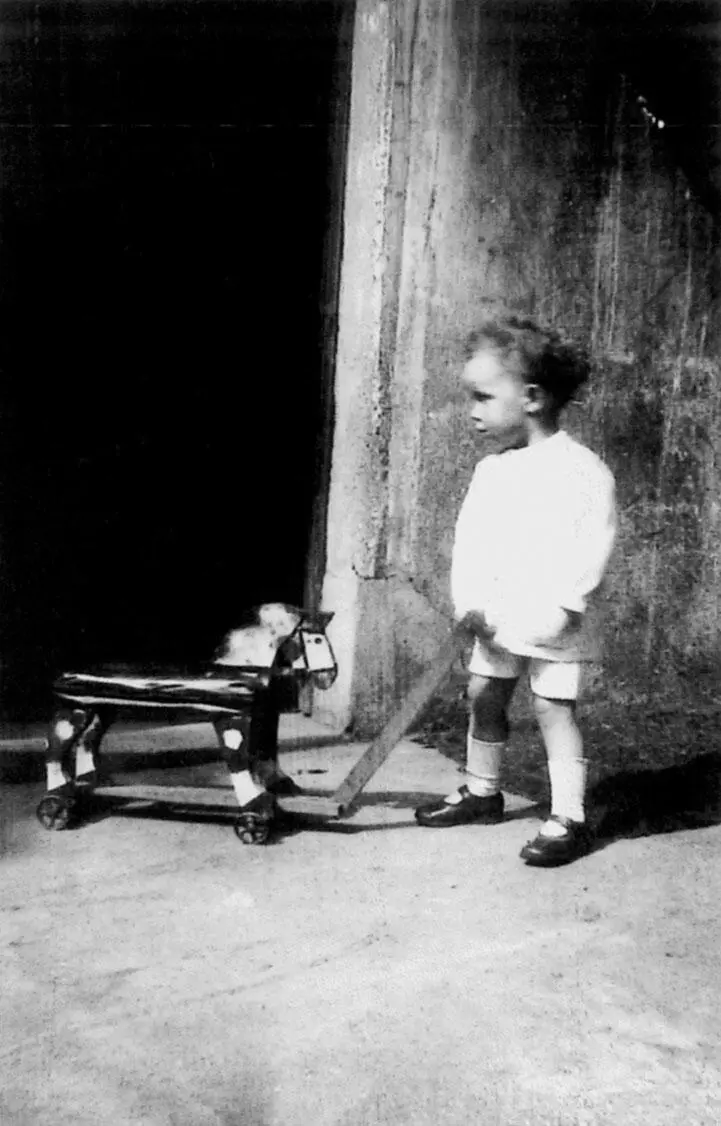

Some of the earliest photos of Eric with his mother, Sadie.

The future Mr Eric Morecambe, OBE.

Lancaster Road Junior School, Morecambe. Eric is second from the left on the front row.

In many ways, Eric’s was a typical working class childhood. His parents were far from affluent (when they went shopping in Lancaster, several miles away, they used to walk home to save the bus fare) but Eric never went hungry. And though money was often pretty tight, he never ran short of fun things to do. On Sundays George would take him fishing, and on Saturdays they’d go to a football match – usually Morecambe, sometimes Blackpool, occasionally mighty Preston North End. Yet there was one aspect of his upbringing that was highly unusual, at least for those days. He was an only child. This oddity was to prove crucial for his future prospects. Had he been one of six children, like his mother, or one of eleven, like his father, it’s highly unlikely he would have been able to pursue the same show business career.

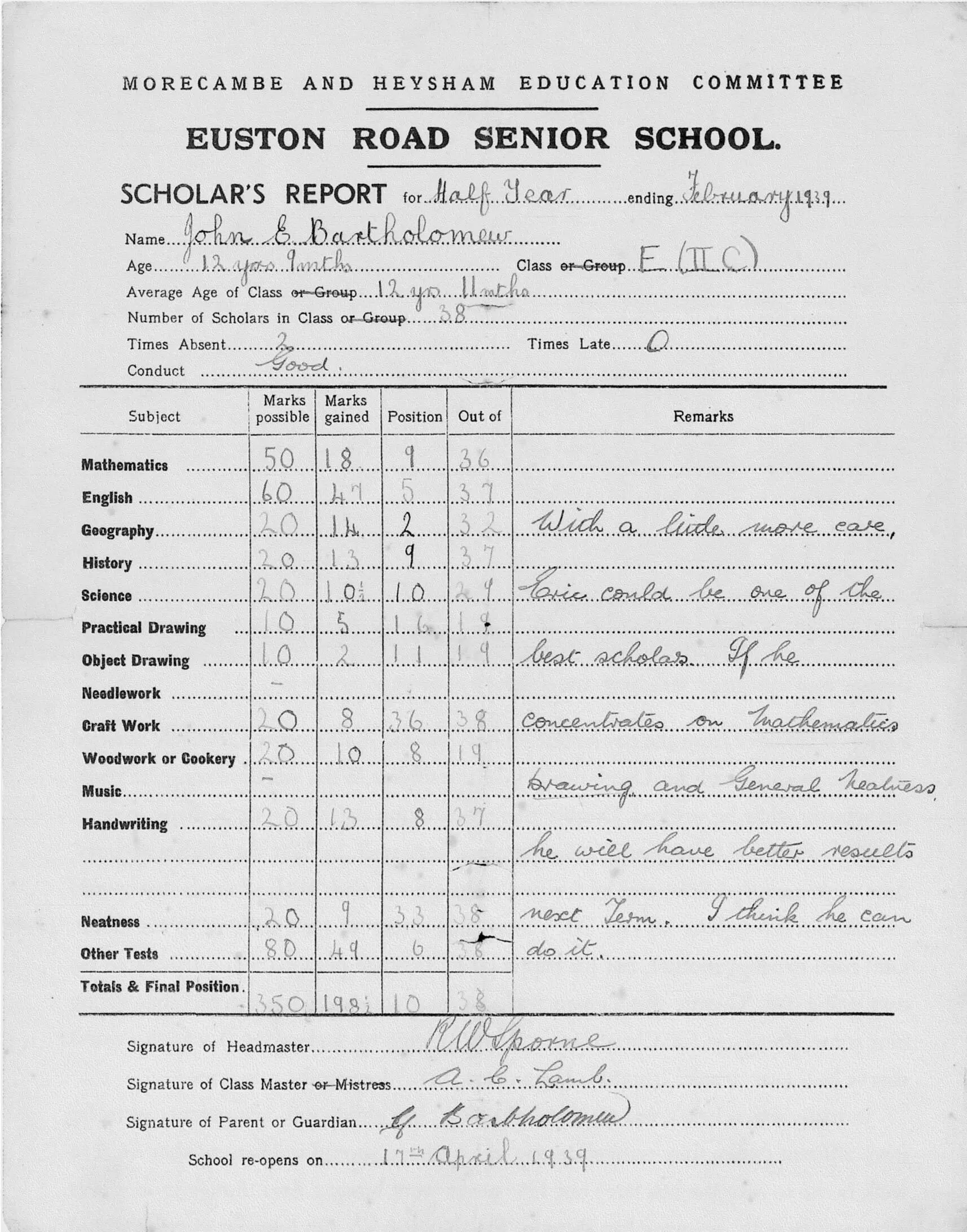

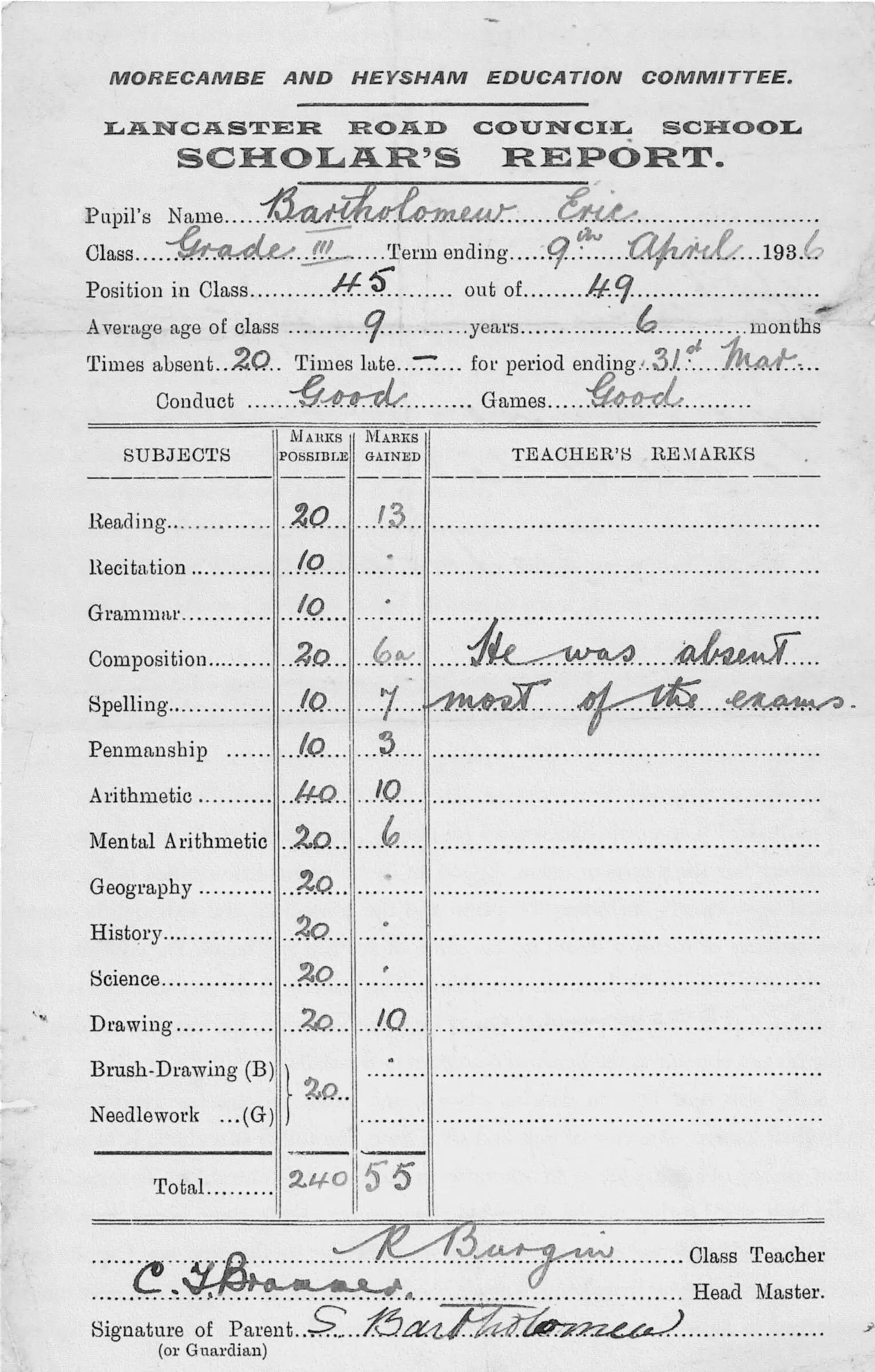

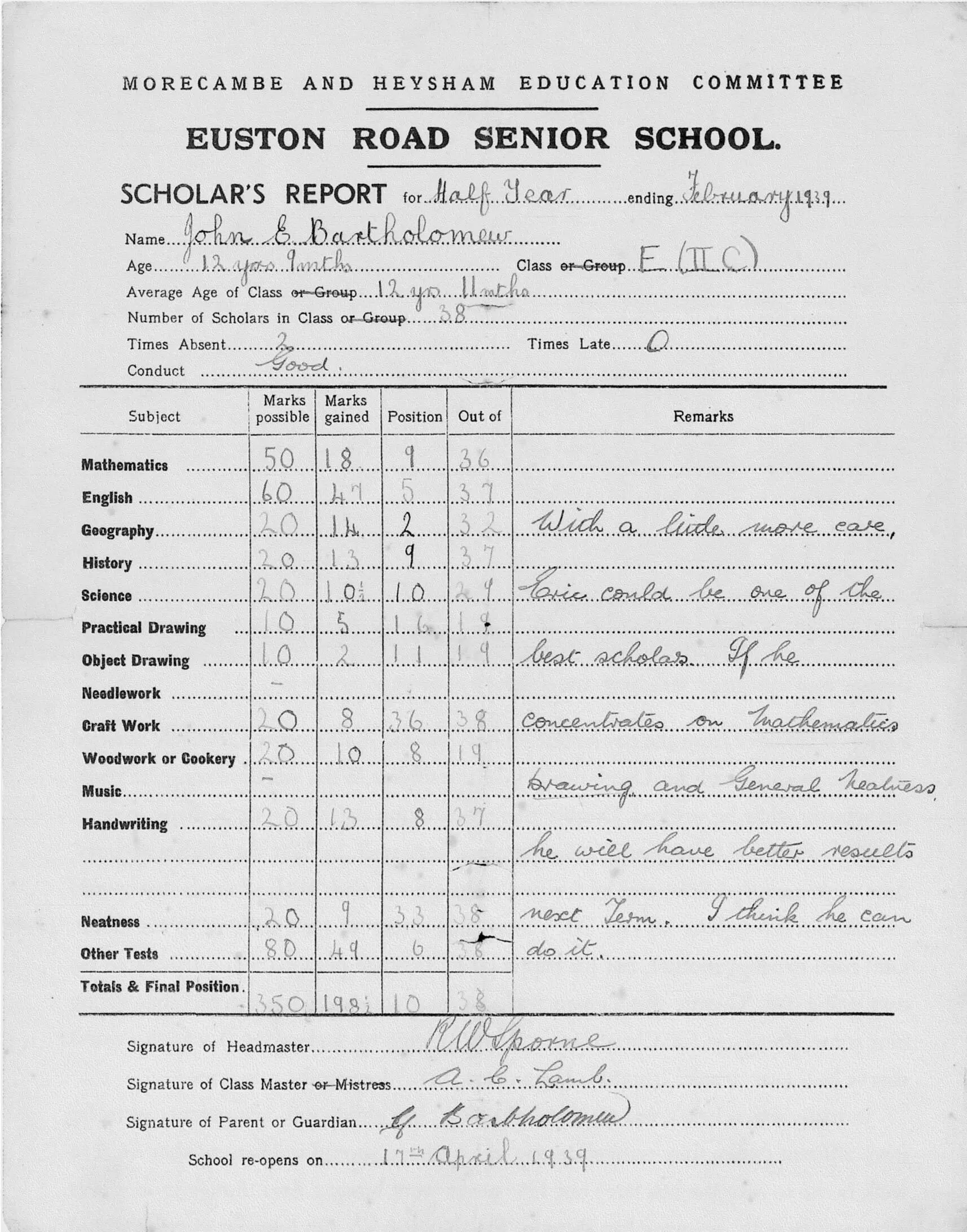

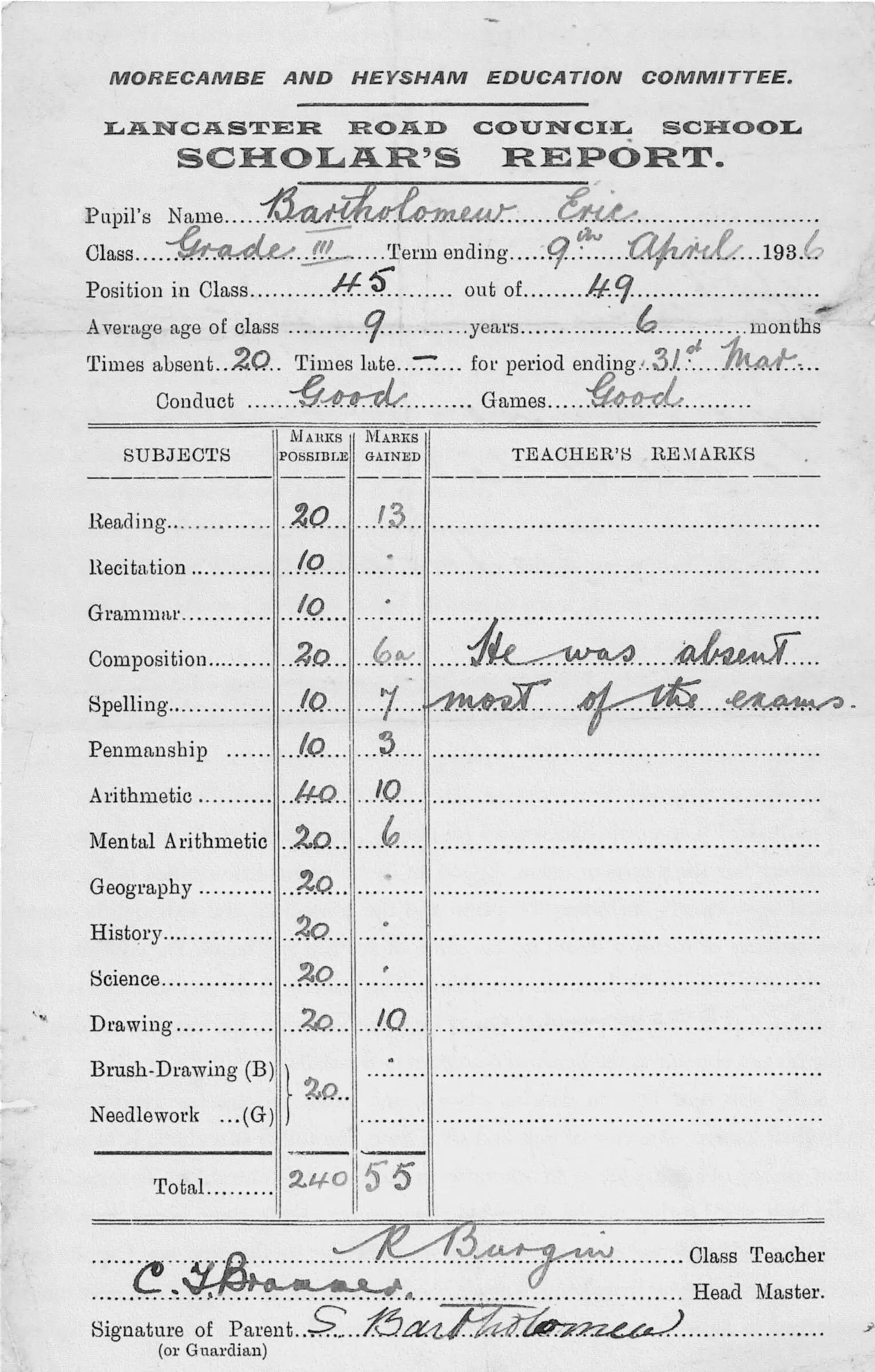

However despite a happy and comparatively comfortable home life, Eric did surprisingly badly at school. ‘I wasn’t just hopeless in class,’ he recalled. ‘I was terrible.’ 1His school reports bear him out. Out of a class of 49, he was ranked 45 – and the other four, according to Eric, never even went to school. Eric’s poor academic performance remains a mystery, especially since Sadie was not only intelligent, but diligent too. ‘I am disgusted with this report,’ she wrote to his headmaster, ‘and would be obliged if you would make him do more homework.’ Her efforts were in vain. When Sadie told the head she wanted Eric to go to grammar school, he told her it would be a waste of time. When she said she’d pay for private education, he said it would be money down the drain. For the time being, at least, Eric was his father’s son. ‘I had no bright ambitions,’ he recollected. ‘To me, my future was clear. At fifteen I would get myself a paper round. At seventeen I would learn to read it. And at eighteen I would get a job on the Corporation, like my dad.’ 2

If there was one thing Eric was good at, it was performing. Ever since he was a toddler, he’d entertained his parents by dancing to the gramophone. Once, he sneaked out of the house and onto a nearby building site, where Sadie found him treating local workmen to a song and dance routine. ‘That little lad’s a wonderful entertainer,’ 3said one of them. ‘I’ll entertain him when I get home,’ 4said Sadie, yet she did all she could to nurture her son’s nascent talent. Egged on by his mum, Eric studied half a dozen musical instruments, including the piano and the accordion, and although he never mastered any of them, it didn’t do his sense of rhythm any harm. He cultivated his showbiz education at the local cinema, although his interest in the movies came second to his interest in making mischief. On at least one occasion, he was thrown out for firing his pea shooter at the heads of bald men in the stalls.

Читать дальше