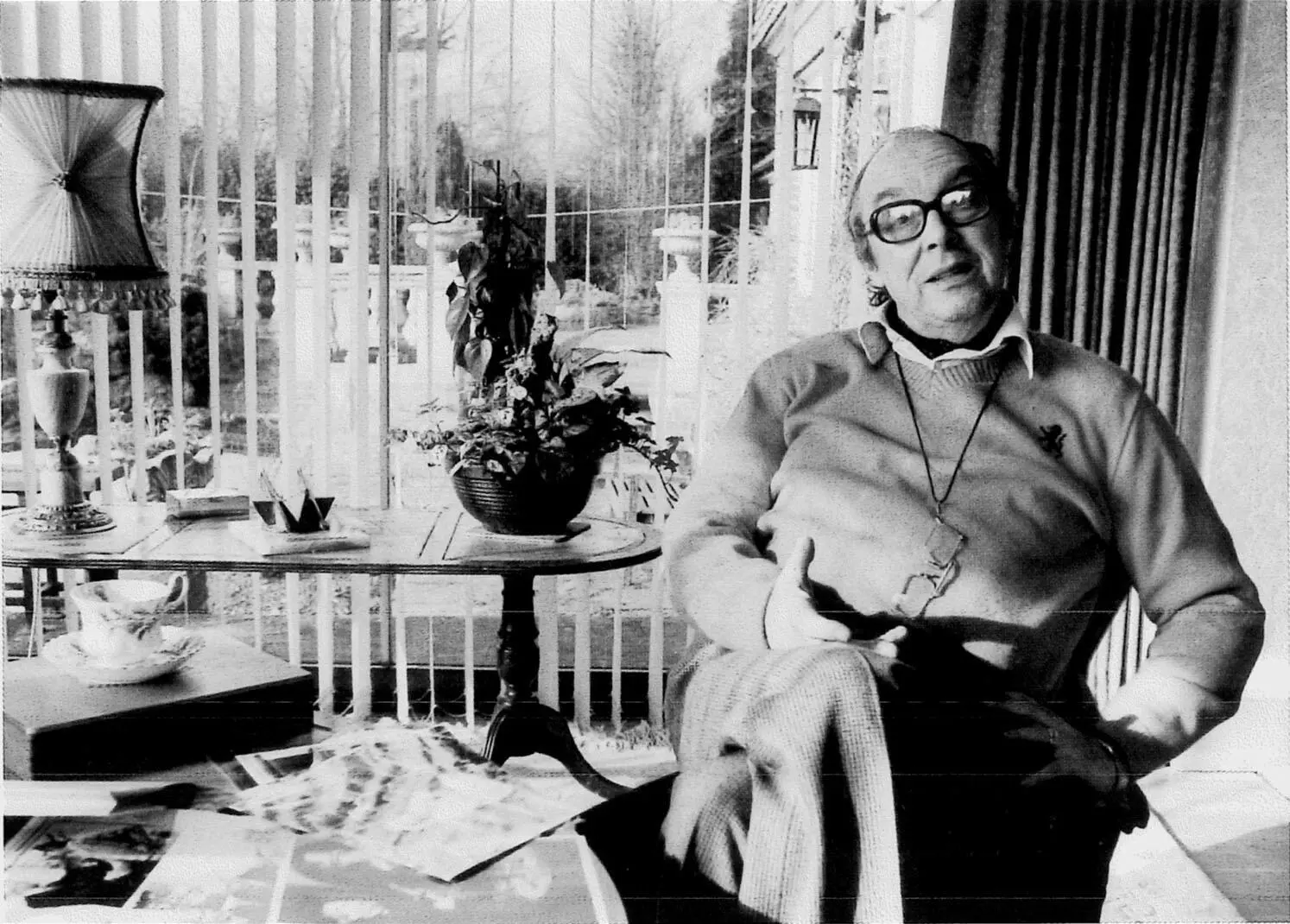

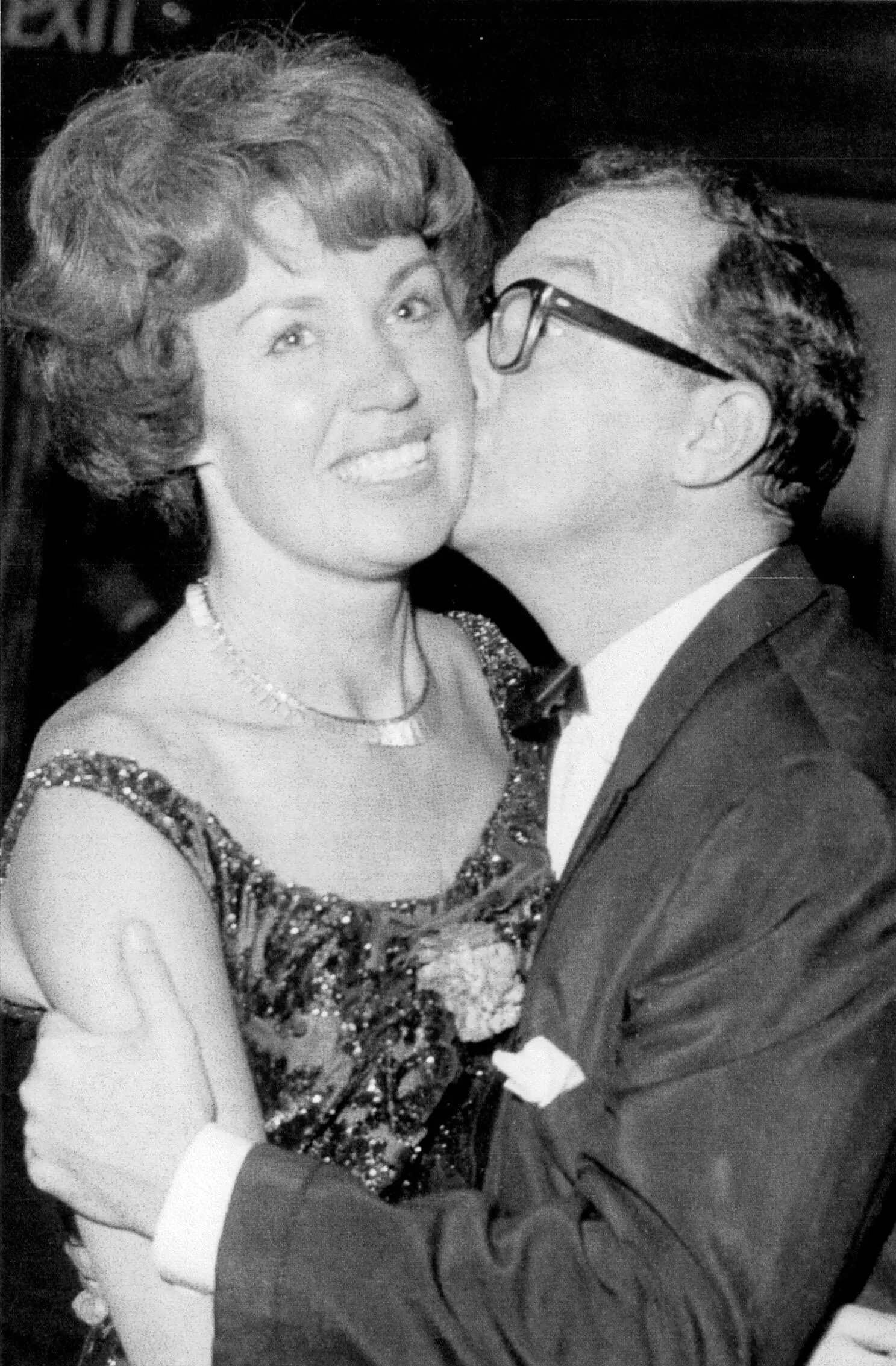

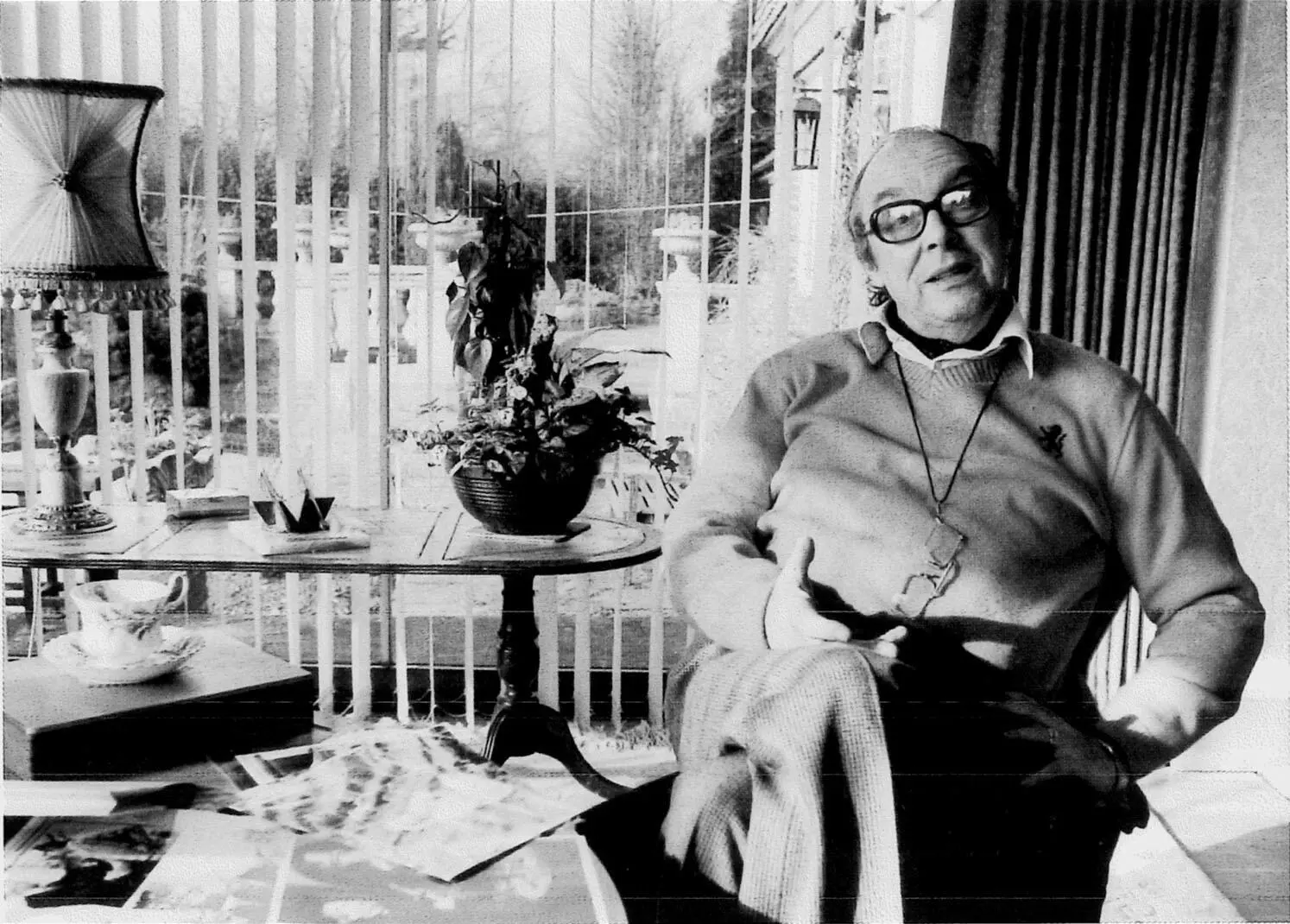

Joan still lives here, just like she used to live here with Eric. She’s never remarried, and she has no plans to move. She still wears his ring, and she still thinks of him as her husband. She sometimes refers to him in the present tense, as if he’s still around. After all these years, she still half expects to see him pop his head around the door. ‘To me it always seems as if Eric’s only just gone,’ she tells me. ‘It never seems to me that it’s been twenty years.’ Yet after today, there will be slightly less of Eric here than there was before. After twenty years, she’s been clearing out her husband’s study – a room that had lain dormant since he died. There was all sorts of stuff in there – photos, letters, joke books, diaries. It sounded as if there might be a book in it. ‘You can’t explain it,’ says Joan. ‘You can’t explain why people still remember him as if he’s still part of their lives.’ She’s probably right. You can never really explain these things – not definitively, not completely. But once I’ve spent a few hours inside Eric’s study, I reckon I’ll have a much better idea.

We go upstairs, past his full length portrait in the stairwell, and into a small room – barely more than a box room, really – where Eric would retreat to read and write. There’s a lovely view out the back, across the golf course and over open fields beyond, where Eric would go golfing or bird watching. He quite liked a round of golf, but on the whole he far preferred birds to birdies. He loved to watch them fly by, especially when he was resting.

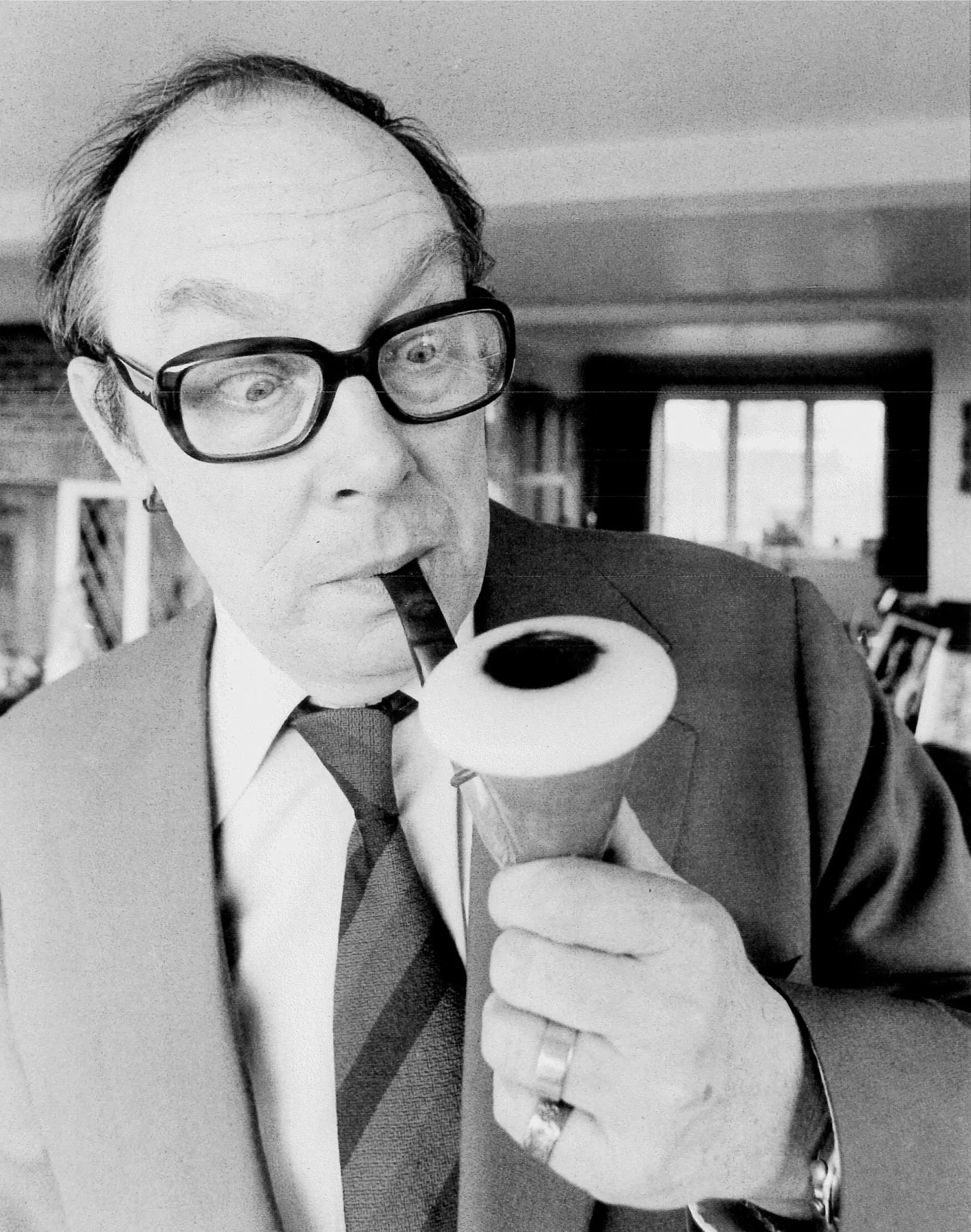

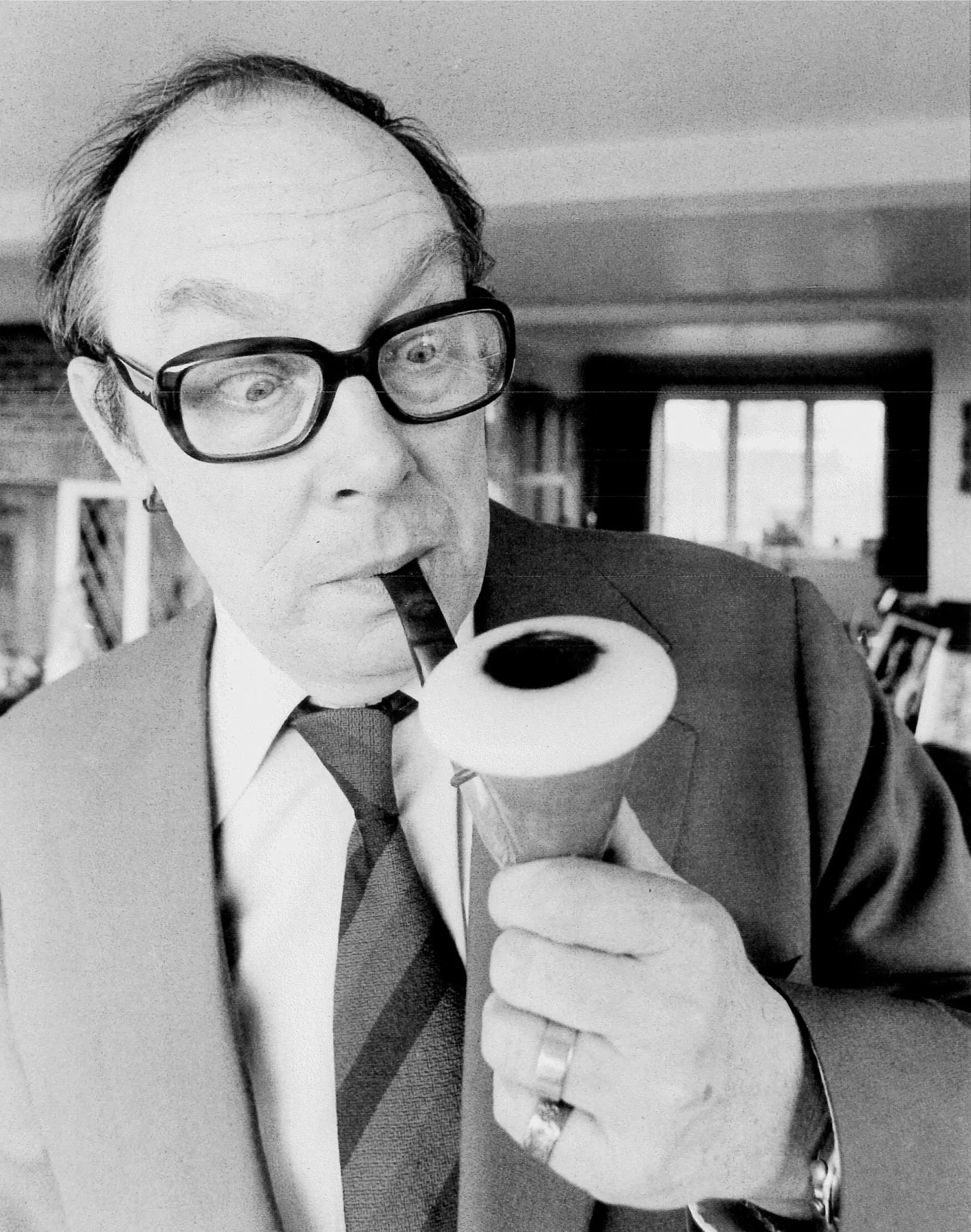

However there’s nothing restful about this room, despite its peaceful vistas. This was where Eric came to work, not just to rest or play. ‘This book laden room was his shrine,’ observed Gary, just a few days after his father’s death. ‘Almost every previous time I had entered it, I had discovered his hunched figure poised over his portable typewriter, the whole room engulfed with smoke from his meerschaum pipe.’ 2Two decades on, that same sense of restless industry endures. It may be twenty years, but it feels like Eric has just nipped out for an ounce of pipe tobacco. It feels like he’ll be back any minute. It feels as if we’re trespassing in a comedic Tutankhamen’s tomb.

On the floor beside the bookcase is an old biscuit tin. Inside is his passport, his ration book and his Luton Town season ticket. There’s a shoe box full of old pipes, with blackened bowls and well chewed stems. Here’s his hospital tag, made out in his real name, John Bartholomew, so he wouldn’t be pestered by starstruck patients. On the back of the door is his velvet smoking jacket – black and crimson, like a prop from one of Ernie’s dreadful plays. ‘He loved dressing in a Noel Coward kind of way,’ says Gary, vaguely, his thoughts elsewhere. But it’s the books on the shelves above that really catch your eye. Never mind Desert Island Discs. For the uninvited visitor, there’s nothing quite so intimate as someone else’s library. When you scan another person’s bookshelves, it’s as if you’re browsing in the corridors of their mind.

As you might expect, there are stacks of joke books: Laughter, The Best Medicine; The Complete Book of Insults; Twenty Thousand Quips And Quotes. And as you might expect, there are stacks of books about other jokers, many of them American, from silent clowns like Buster Keaton to wise guys like Groucho Marx. Yet it’s the less likely titles that reveal most about Britain’s favourite joker: PG Wodehouse, Richmal Crompton, even the Kama Sutra. And here’s Charles Dickens’ The Pickwick Papers, ‘Eric always told me that The Pickwick Papers was the funniest book he had ever read,’ says Gary. ‘He used to read it on train journeys when he was travelling from theatre to theatre, from digs to digs. He said he’d get strange looks from the people in his carriage, because he was stifling his laughter as he read.’ There’s Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead. There’s a bit of Eric in all these books – well, maybe not the Kama Sutra. Wodehouse? Certainly. Dickens? Of course. Eric and Ernie would have been brilliant as Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, but the character Eric most resembles is Crompton’s Just William, an eternal eleven year old with a genius for amiable mischief. ‘Maybe that’s why we loved him as kids,’ says Gary’s lifelong friend, Bill Drysdale, a regular visitor to this house ever since he was a child. ‘The thing that kids love more than anything is the idea of grown ups being naughty. Kids think that’s just the funniest thing, and that’s what I always loved about him.’

Eric wasn’t just a pipe smoker, he was a pipe collector too. He owned several hundred pipes. This one, which he called his Sherlock Holmes pipe, was a particular favourite

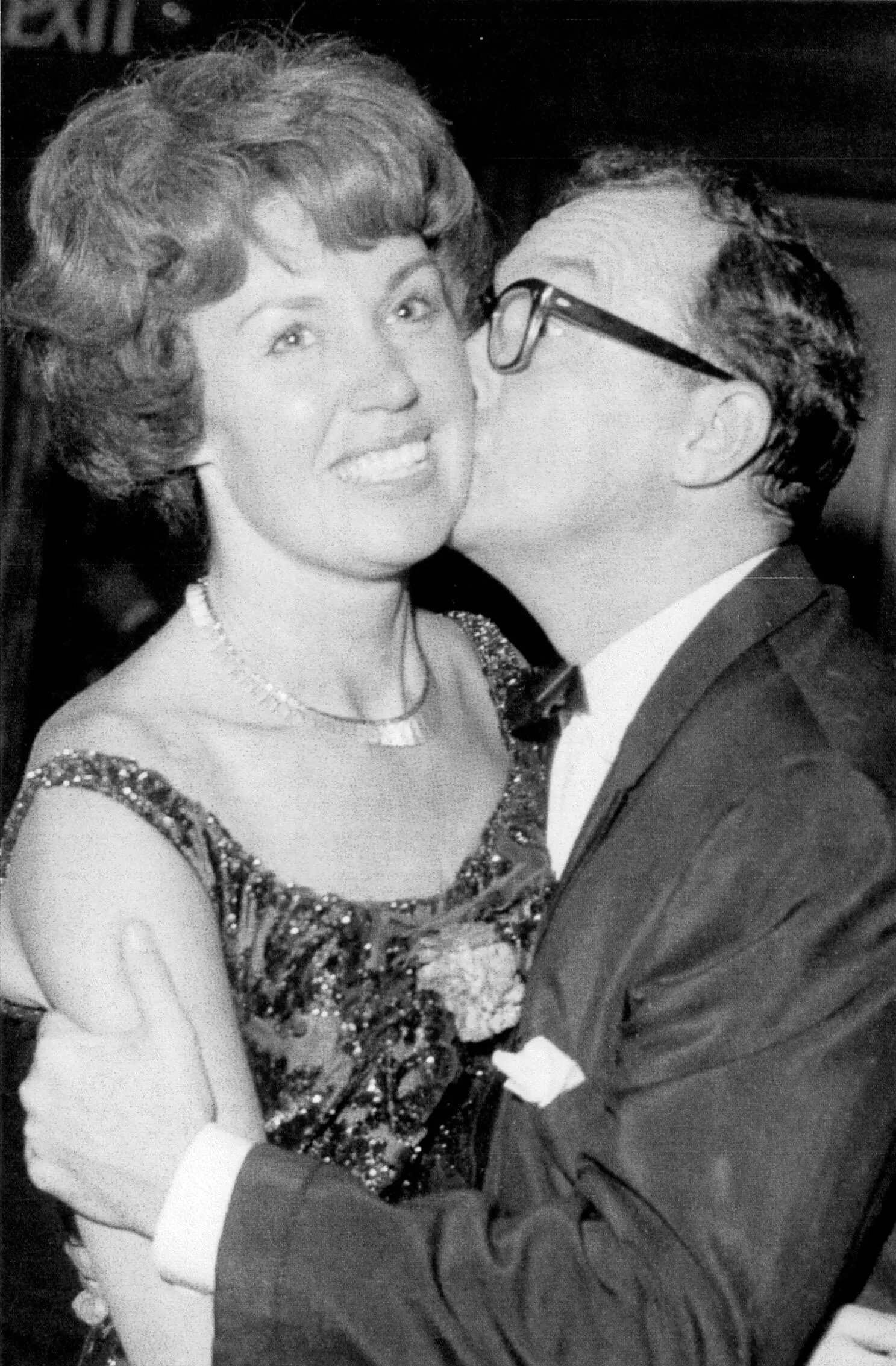

Mr and Mrs Eric Morecambe

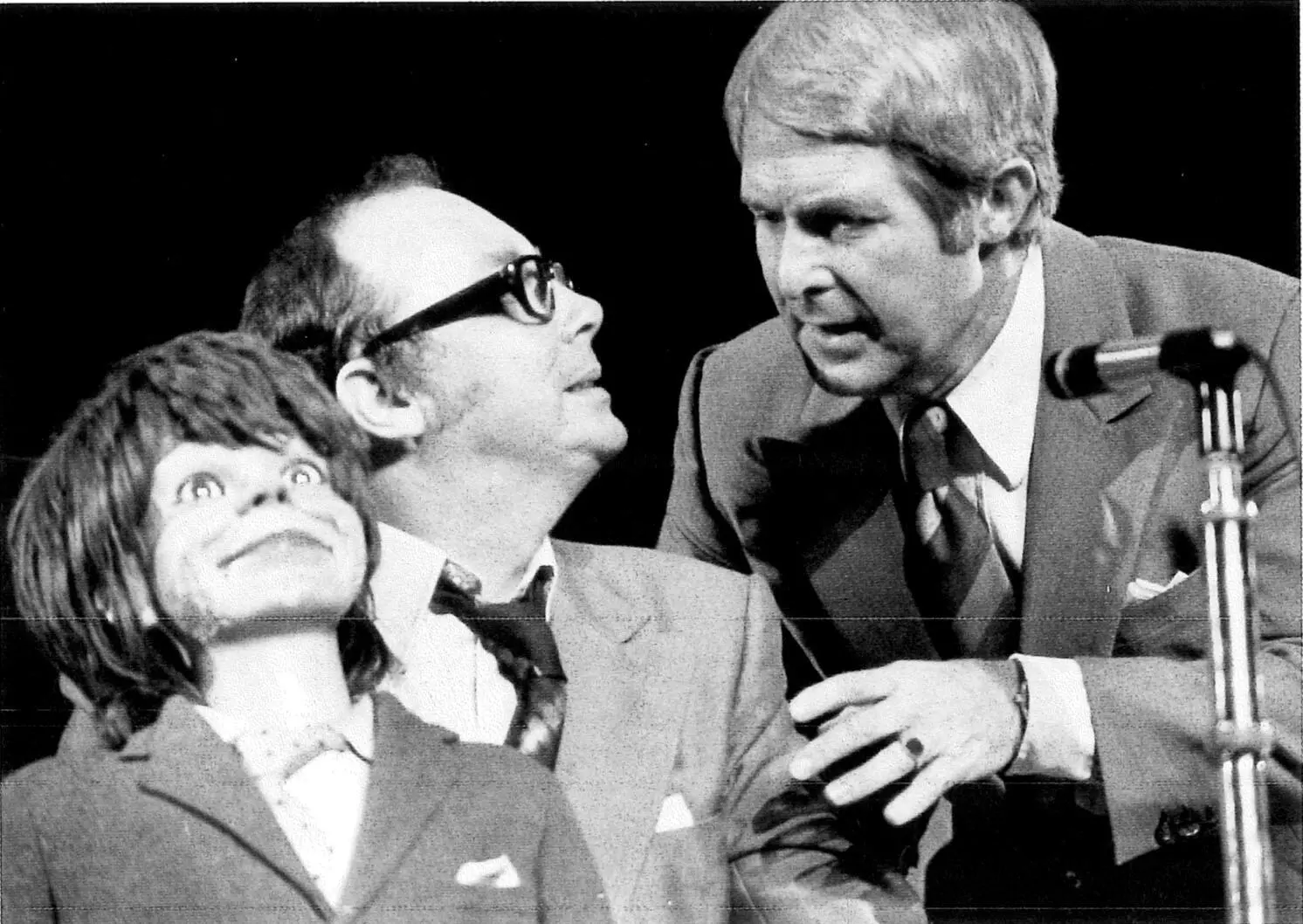

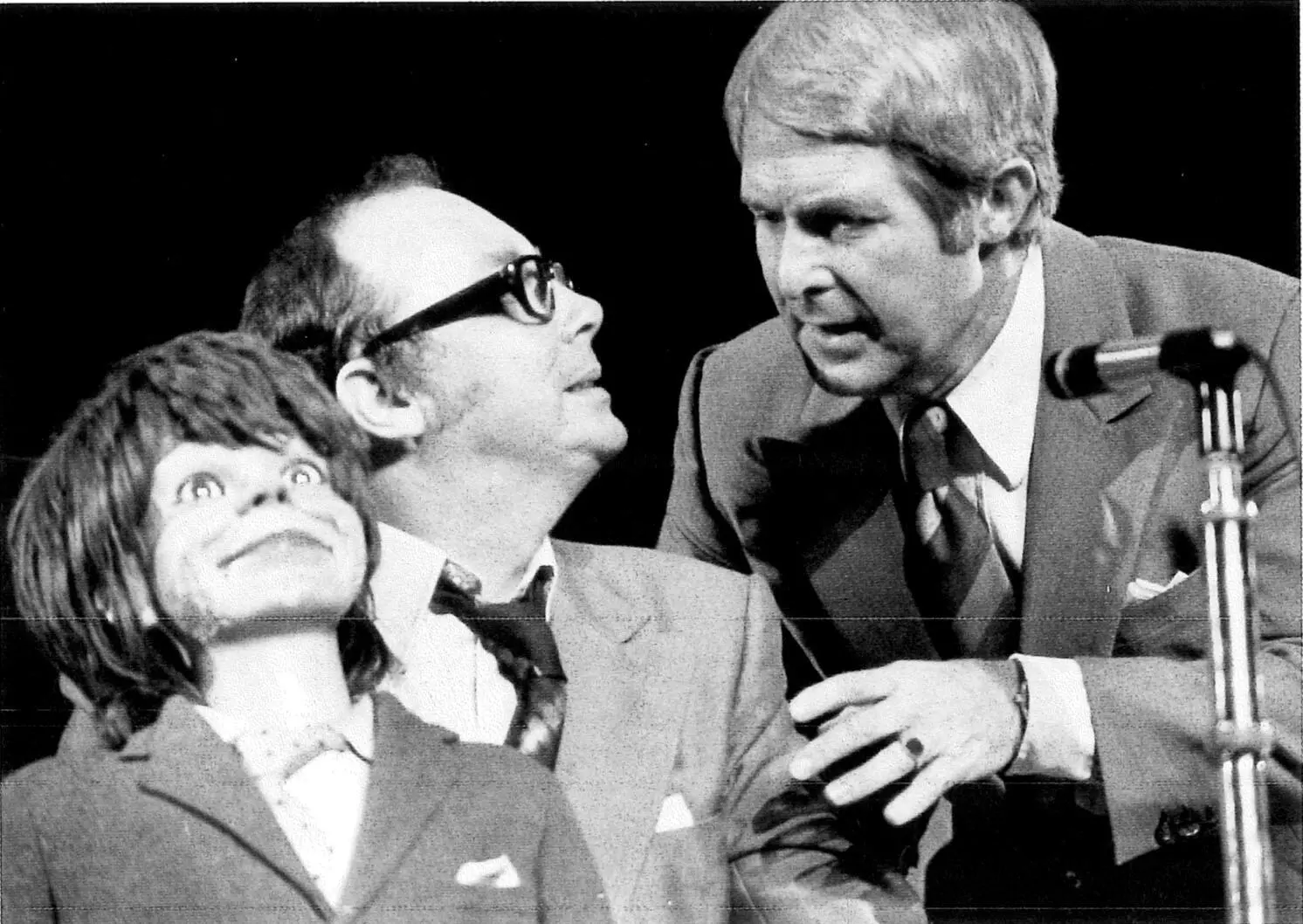

Ernie: ‘I can see your lips moving. Eric: Well of course you can, you flaming fool! I’m the one who’s doing it for him! He’s made of wood! His mother was a Pole!’ Right to left: Ernie, Eric and Charlie the Dummy, who still resides at the Morecambe residence in Harpenden, awaiting repairs.

As a child, Bill wasn’t remotely awestruck by Eric’s stardom. ‘I never felt alienated by his status,’ he says. ‘You always felt like he was one of us.’ Yet he was full of surprises. After Eric died, Bill found a Frank Zappa album, of all things, in Eric’s record collection. ‘There was often the appearance of anarchy, but there was one person at the centre of things who knew exactly what was going on,’ says Bill, of Zappa’s music, ‘and that is an ideal template, I think, for Eric’s comedy.’ Eric’s comedy wasn’t just a job. It was a way of life. ‘His mind was always working on comedy,’ says Bill. ‘He’d be working in the study, he’d come out and he’d try out a joke on Gary and I, just to see what we thought of it, to see if it was funny.’ He knew if children found it funny, it would be easy to make their parents laugh.

We walk down the narrow corridor, to Eric’s old bedroom. The overflow from his study is strewn across the floor. There’s the giant lollipop which was his trademark before he met Ernie – a twelve year old vaudevillian, kitted out in beret and bootlace tie. 3Here’s a clapperboard from The Intelligence Men, the first feature film he made with Ernie. And there’s the ventriloquist’s dummy that was the highlight of their live show. ‘I can see your lips moving,’ Ernie would protest each time, in immaculate mock indignation. ‘Well of course you flaming can, you fool!’ Eric would answer, furious at this outrageous slur on his professional integrity. ‘I’m the one who’s doing it for him! ‘He’s made of wood! His mother was a Pole!’ ‘He had the common touch,’ says Gary. ‘He wasn’t trying to be hip or clever.’ But that was another part of Eric’s artifice. Eric did what all great artists do. He made it look easy.

There are heaps of photos all around us, some dating back to Eric and Ernie’s first turns together, as teenagers during the war. With his boyish good looks and eager grin, Ernie looks just the same as he always did. Eric, on the other hand, is almost unrecognisable – painfully thin and curiously feminine, with high cheekbones and a full head of dark, wavy hair. There are piles of cuttings too, newspaper after newspaper – countless rave reviews, even the occasional stinker. So important at the time, or so it seemed. All forgotten now, of course. As Eric used to say, to buck himself up after a bad notice, or bring himself back down to earth after a good one, the hardest thing to find is yesterday’s paper. And here they all are – all his daily papers from all his yesteryears. There are endless interviews, in every publication you can think of (and quite a few you can’t) from a profile by Kenneth Tynan in The Observer to a cover story in that classic boy’s comic, Tiger. Today these faded clippings all seem incongruously similar. Highbrow or lowbrow, they’re all mementoes of a life lived almost entirely in the public gaze.

Читать дальше