You see the

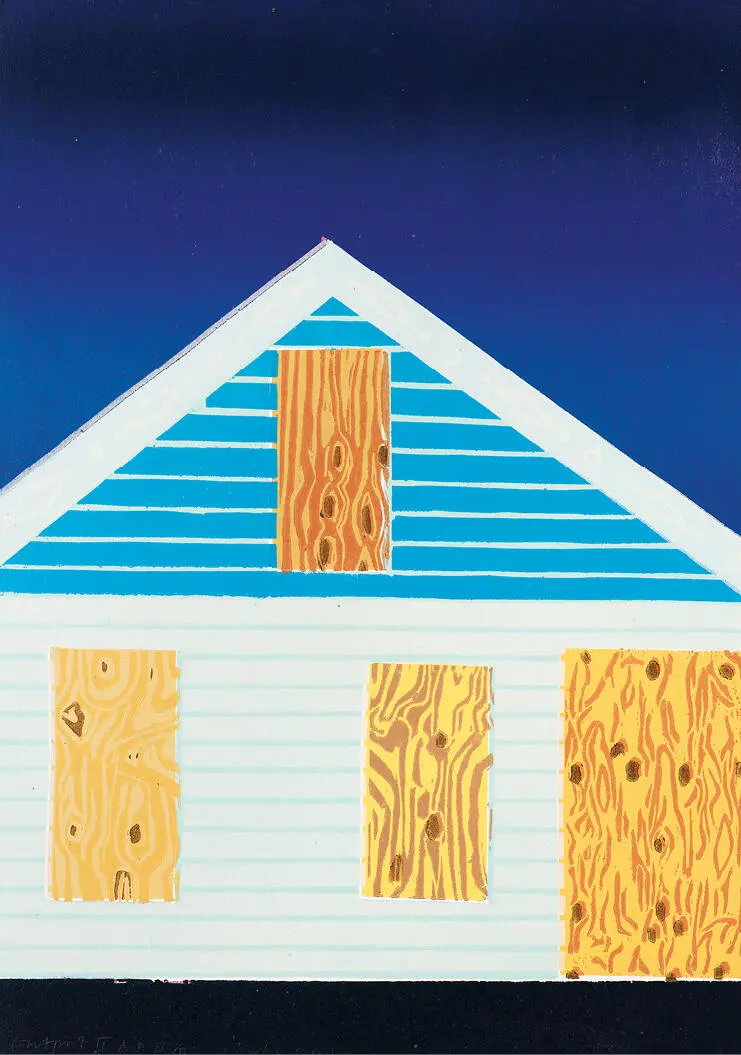

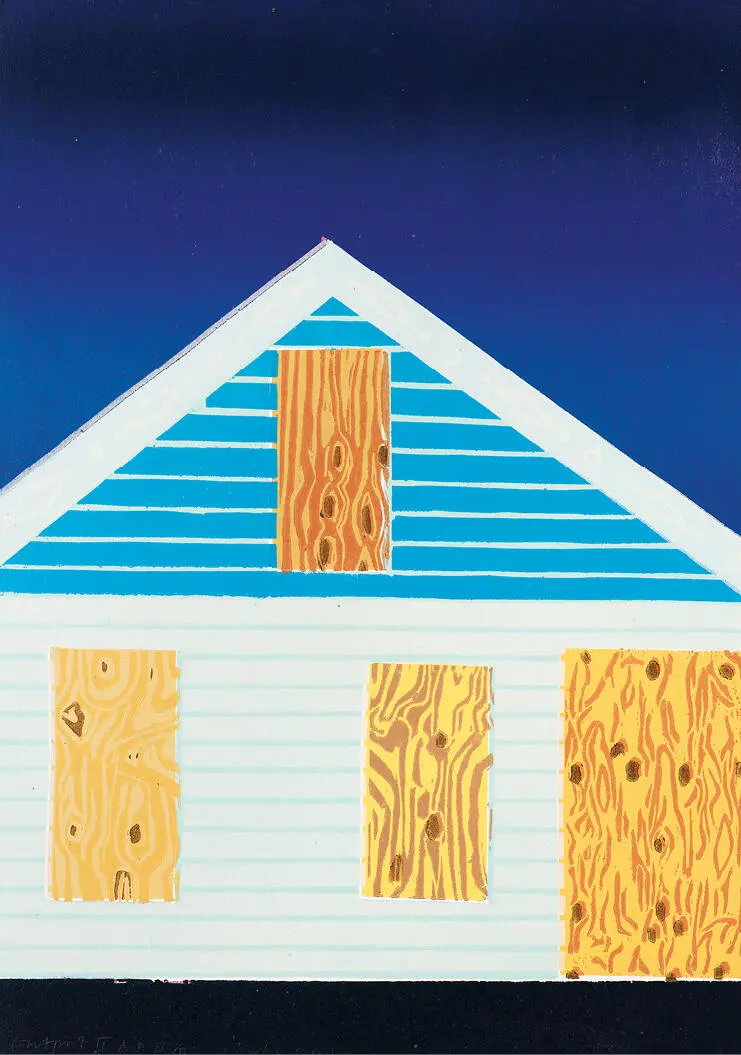

It is a tiny eruptive nodule of poetic substance focused on a ruined building, a small cottage or shed.

He pulls back a foot or two and starts again:

Though open to the sky yet stained with smoke

You see the swallows nest has dropp’d away

A wretched covert ’tis for man or beast

And when the poor mans horse that shelters there

Turns from the beating wind and open sky

The iron links with which his feet are clogg’d

Mix their dull clanking with the heavy sound

Of falling rain a melancholy

That has come easily, without correction, on this otherwise heavily corrected sheet, so materially realised that it seems likely to have been something seen by Wordsworth on his walks in Dorset. This poetry is already autobiographical, and its atmosphere describes the man Wordsworth was in his darkest hours. ‘You’ is ‘you’ the reader or the passer-by; it is also Wordsworth himself, and the ‘you’ also seems identified with the horse and his hobbling chains, both man and animal a prisoner, dulled by the conditions life has imposed, sheltering in a wreck of a building for which all hope is gone and which even the swallows have deserted. Coleridge accused Wordsworth of being a ‘ spectator ab extra ’ – an observer from outside whatever conditions or predicament he was describing – but here the ‘covert’, the hiding place, is wretched for man or beast, no matter which, and all these creatures – Wordsworth, the horse, the poor man, the swallow, you – are inhabiting the same desolate landscape.

But the setting is not entirely true. There is a whiff of cliché in the air. The magazines of the 1790s were full of tragic scenes of rural poverty, and the word ‘melancholy’ seems to bring the movement to a halt. So Wordsworth stops and tries again:

And when the poor mans horse that hither comes

For shelter turns ab

That too, for whatever reason, is a dead end. And he takes another run:

And open sky the passenger may hear

The iron links with which his feet are were clogged

Mix their dull clanking with the heavy sound

Of falling rain, a melancholy thing

To any man who has a heart to feel. –

Those final words at last ring with an air of Wordsworth’s own truth. That is his subject: the grandeur in the beatings of the heart.

But whatever this poem is, it won’t come clean. He introduces his own recent visit to the cottage:

But two nights gone

I chanced to I passed this cottage and within I heard

The poor man’s lonely horse who that hither comes

For shelter, turning from the beating rain

And open sky, and as he turned, I heard

At one level the horse was a ‘who’, but Wordsworth revises that to the more conventionally impersonal ‘that’. The various elements and players need to be organised: himself, the horse, the place, the stormy night, the connections between them. The revisions now turn scratchy and directionless:

I heard him turning from the beating wind –

And open sky and as he turn’d I heard

But he cannot decide what the horse is doing there: ‘to weather the night storm’ or ‘to weather out the tempests’? ‘Within these walls’, ‘within these roofless walls’, or ‘these fractur’d walls’? Then, at draft twelve of these few recalcitrant lines, another set of ingredients appears which suddenly mobilises this dark fragment of experience:

But two nights gone, I cross’d this dreary moor

In the still clear moonlight, when reached the hut

I looked within but all was still and dark

Only within the ruin, I beheld

At a small distance on the dusky ground

A broken pain which glitter’d to the moon

And seemed akin to life. – Another time

The winds of autumn drove me oer the heath

Heath in a dark night by the storm compelled

the hardships of that season

I crossed the dreary moor

Those lines are still in thrall to an earlier way of doing poetry – ‘dusky’ is dead jargon; ‘glitter’d to’ is patently false language – but that broken pain/pane of glass on the dark floor of the ruined shed, a lifeless thing that seems to be full of life, grips and obsesses him:

I found my sickly heart had tied itself

Even to this speck of glass – It could produce

a feeling as of absence

on the moment when my sight

Should feed on it again. For many a long month

I felt Confirm’d this strange incontinence; my eye

Did every evening measure the moon’s height

And forth I went before her yellow beams

Could overtop the elm-trees oer the heath

I sought the r and I found

That speck more precious to my soul

Than was the moon in heaven

Here now at last are the elements for a strange and lonely poem of experience on the edges of despair, an act of empathy. It is driven by an obsessive and disordered frame of mind, dissociated from the normalities of human love and community, in a world where, in its final form, a looming morbidity infects and pollutes all living things. It is a poem written by the desperate man Coleridge had come to cure.

Incipient Madness

I crossed the dreary I crossed the dreary moor

In the clear moonlight when I reached the hut

I enter’d in, but all was still and dark

Only within the ruin I beheld

At a small distance, on the dusky ground

A broken pane which glitter’d to in the moon

And seemed akin to life. There is a mood

A settled temper of the heart, when grief,

Becomes an instinct, fastening on the all things

That promise food, doth like a sucking babe

Create it where it is not. From this hour time

I found my sickly heart had tied itself

Even to this speck of glass – It could produce

a feeling as of absence

on the moment when my sight

Should feed on it again. For many a long month

I felt Confirm’d this strange incontinence; my eye

Did every evening measure the moon’s height

And forth I went soon as her yellow beams

Could overtop the elm-trees. Oer the heath

I went, I reached the cottage, and I found

Still undisturbed and glittering in its place

That speck of glass more precious to my soul

Than was the moon in heaven. Another time

The winds of Autumn drove me o’er the heath

One gloomy evening: By the storm compell’d

The poor man’s horse that feeds along the lanes

Had hither come within among these fractur’d walls

To weather out the night; and as I pass’d

While restlessly he turn’d from the fierce wind

And from the open sky, I heard, within,

The iron links with which his feet were clogg’d

Mix their dull clanking with the heavy sound noise

Of falling rain. I started from the spot

And heard the sound still following in the wind

These lines, firmly in a gothic tradition, nevertheless stand as a challenge to everything the eighteenth-century inheritance of elegant rural landscapes might have suggested or proposed. The heart of what Wordsworth sees is not the well-framed picture but the broken pane of glass, and the haunted sound of chains blown towards him on the vast and homeless winds of heaven. There is no connection yet to any larger significance – any movement beyond the gothic – that connection would have to wait until Coleridge had changed his relationship to the world.

There was one more poem, his most recent, that Wordsworth was keen to have Coleridge hear, and it marked an emergence from this darkness. He read him this first version of ‘The Ruined Cottage’, not giving it to him to read but making sure he heard it from his own lips. It is a descendant of the dark poetry which had poured out of him over the previous six or nine months, but this is different. In ‘The Ruined Cottage’, suffering and the disordered world are seen in tranquillity. The gothic furniture has been dispensed with, much of it hived off into ‘Incipient Madness’. Instead, a calm and beneficent air emerges from a sad and simple story of suffering and failure, nothing over-heightened, no melodramatic lighting, but a rich simplicity in language and setting by which the place itself of the ruined cottage and its surroundings comes to portray the people whose lives it describes. His previous rhetorical habits have dropped away. Abstractions and pat responses are banished in favour of the tender, corporeal realities in the life of a poor woman and her family.

Читать дальше