The fantasy spy novels of Ian Fleming and his many imitators may have been regarded as somewhat risqué, but nowhere near as salacious as, say, the works of Harold Robbins or Mickey Spillane – and if you were caught reading them you could be in trouble. The adventure thrillers of Alistair MacLean and Hammond Innes were perfectly acceptable, almost innocent, as they contained no sex or bad language, usually had upright, decent (British) heroes and were jolly exciting ‘ripping yarns’. The new generation of spy fiction novelists were not only seen as acceptable, reading them was positively encouraged. When at school, Graham Greene’s thirty-year-old novel Brighton Rock was one of the set texts for my O Level English Literature exam. By the early Seventies, the novels of John Le Carré were on the syllabus.

For male readers of all ages, Fleming, Deighton, Le Carré, MacLean and Innes were instantly recognisable. The dedicated follower of the fashion in thrillers was also familiar with Blackburn, Lyall, Gardner, Leasor, Clifford, Mayo, Jenkins, Mather, Hall, Francis, Canning and a host of others. New names appeared on the covers of paperbacks every week, or if the names were not exactly ‘new’, the covers were.

During the Golden Age of the Thirties it had been as if almost anyone – or at least anyone who was upper middle-class and reasonably well-read – could turn their hand to a detective story. In the Sixties, it was as if the same applied to thriller writing, with the prospect of substantially greater rewards. But were being middle-class and well-read sufficient qualifications? A classic English detective story might never leave the setting of a country house or a vicarage and require no more technical background knowledge than the use of pipe-cleaners, the distribution of keys among the senior servants, and when the clock in the hall is wound for the night. Thrillers had more exotic settings, usually foreign, and needed less domestic but far more technical information: on guns, on surviving a desert, a storm at sea, on a glacier or an ice flow, on radios, on navigation, on codes and the tradecraft of spies, on mixing with lowlife, on unarmed combat, and on enjoying the high life. Since the Bond books, it was de rigueur that every special or secret agent would eat only the finest foods and drink only the most expensive wines or elaborate cocktails, and though many of the descriptions of the licensed-to-kill gourmand never held up to really close scrutiny, 3they had to appear plausible.

All of which meant that the writer of a good thriller had to be an experienced traveller conversant with foreign lands and cultures, who had enjoyed a varied and exciting, not to say dangerous, life – at least one more exciting than his (as it was invariably a ‘he’) readers. Surely not everyone could have such an interesting life, so who did?

There were few tinkers and probably even fewer tailors tempted to try their hand at thriller-writing in the boom time of the Sixties and Seventies, but many who did had certainly been soldiers or sailors – or airmen during World War II or in National Service and a large proportion were members of Her Majesty’s Press.

Of the 175 authors mentioned in this study for whom career details are known, almost 75 per cent had experienced active military service other than peacetime National Service, or were professional journalists, in some cases both. Among other professions, teaching provided the biggest single breeding-ground for those seeking bestsellerdom, though of course careers often overlapped. Alistair MacLean, for example, had served in the Royal Navy during the War but was a school teacher when HMS Ulysses was published.

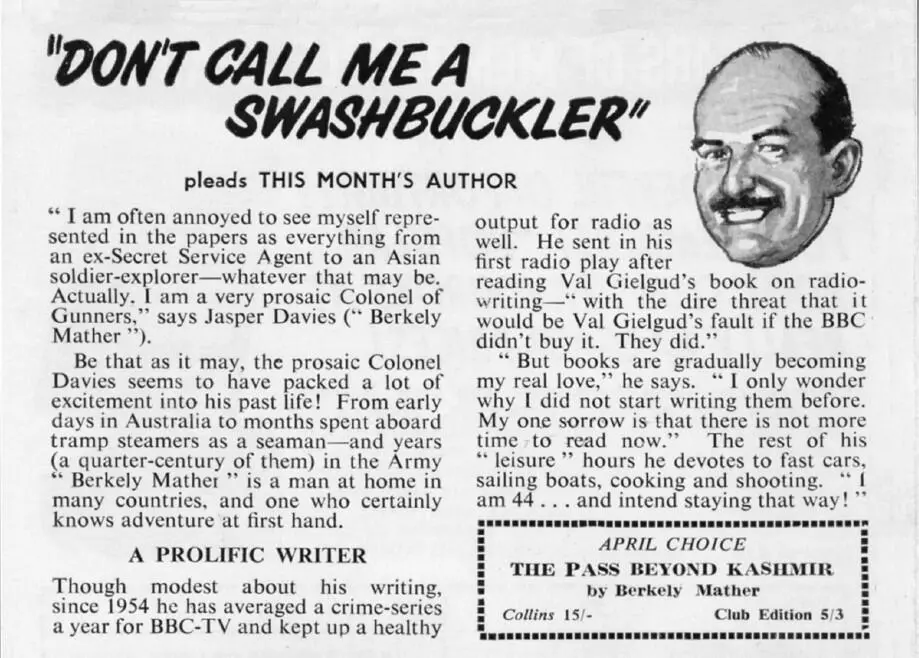

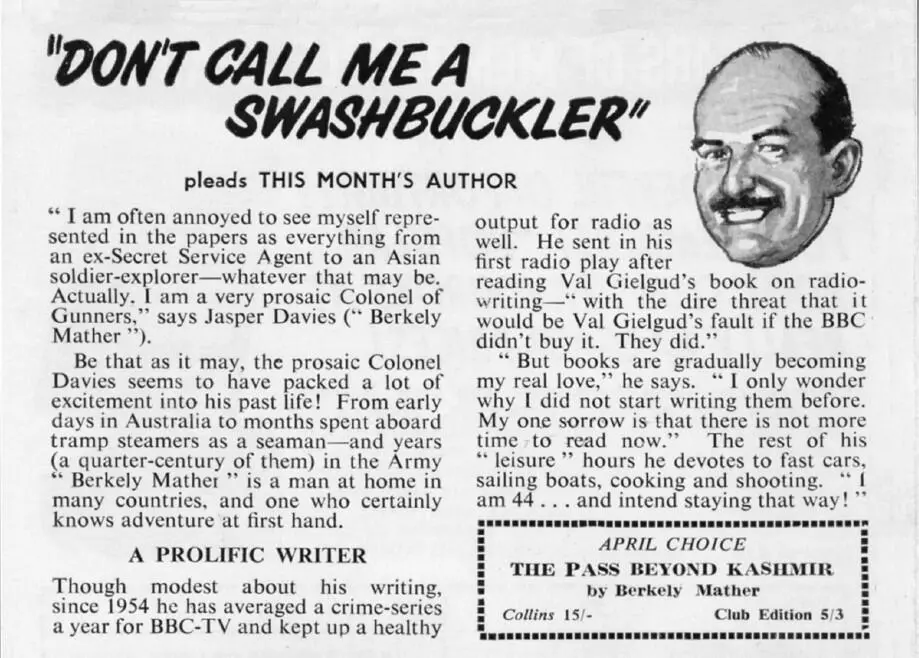

Given the popularity of war stories, it was to be expected that anyone with actual wartime experience and a modest grasp of basic English would fancy their chances supplying stories to a growing and seemingly insatiable market. Notable military ‘veterans’ included Berkely Mather – a career soldier for twenty years before taking to writing radio and television plays and then thrillers, Francis Clifford – a genuine war hero, Clive Egleton – a long-serving professional soldier, Eric Ambler, Victor Canning and Hammond Innes, who all saw wartime service in the Royal Artillery. Also, John Gardner and James Leasor, who both served with the Royal Marines, John Michael Brett and Adam Hall were in the RAF, and Lionel Davidson and Antony Melville-Ross served in submarines throughout WWII.

Quite a few that we know of had worked for the British Intelligence services. Famously, Graham Greene had served in MI6, as had Kenneth Benton and Ian Fleming in Naval Intelligence during the war and John Le Carré, John Bingham and Antony Melville-Ross during the Cold War. Several others had experience of intelligence or counter-intelligence work during their military careers, for example: Ted Allbeury, Clive Egleton, Francis Clifford and Berkely Mather.

It is also worth mentioning that of the few (five) women thriller writers in this period, other than Helen MacInnes who, in the words of American academic Professor B. J. Rahn ‘always seemed to be flying solo’, two also had similar useful experiences. Joyce Porter had served throughout the Fifties in the Women’s Royal Air Force where she learned Russian in order to work in Intelligence, and Palma Harcourt, after reading classics at Oxford, worked for various branches of British Intelligence including MI6 postings abroad. She began to write her ‘diplomatic thrillers’ in 1974, by which time Joyce Porter (now better remembered in America than Britain) had abandoned comic spies and was concentrating on comic detectives.

The Companion Tenth Anniversary Issue , The Companion Book Club, April, 1962

There were career diplomats (for example, Dominic Torr), three advertising executives, two doctors, several television scriptwriters, two television presenters, and three actors. One of the latter, Geoffrey Rose, had a starring role in a popular BBC drama written by another thriller writer (James Mitchell’s When the Boat Comes In ) as well as a part in the long-running soap opera Crossroads.

The prospect of fame and fortune also attracted disciples from many a respectable, more stable, career. There was an accountant, a research chemist, a brace (at least) of publishers, several advertising and public relations executives, a graphic artist, a merchant seaman, a poet, a senior policeman, a technical writer for the Ministry of Defence, two bankers, a poultry farmer, a football commentator, and a Governor of Bermuda.

Given their access to news sources not in the public domain (which many would call ‘gossip’), their natural links to publishers, and their opportunities for travel – particularly abroad – it was inevitable that journalists and especially foreign correspondents would be tempted into testing their typewriters with a thriller. At least a third of the authors named in this book were journalists by trade, and half of them had been foreign correspondents. It must have seemed, at certain points in the 1960s, that everyone on Fleet Street was bashing out a thriller in their spare moments. After all, journalists led pretty exciting lives – the travel, the deadlines, the expense accounts … Indeed, it is often forgotten that Ian Fleming was rather a good journalist before he created James Bond. Hammond Innes, Desmond Bagley, James Leasor, John Gardner, Duncan Kyle, and Anthony Price were all, among many others, journalists before they were thriller writers.

Foreign correspondents who had reported from Russia were perceived to have an immediate advantage, and several put the experience to good use, notably Ian Fleming, Derek Lambert, Andrew Garve, Donald Seaman and Stephen Coulter (‘James Mayo’). But it was not just the traditional Cold War enemy which provided useful background for a plot or two.

Читать дальше