To schoolboys and men young enough to have missed the war years there was also a certain fascination with the hardware, the equipment, of the Nazi war machine. Their armies moved with lightning speed, they had charismatic commanders (Erwin Rommel, the ‘Desert Fox’, was the ultimate ‘Good German’), plush Mercedes staff cars, powerful motor-bikes, and tanks with names such as ‘Panther’ and ‘Tiger’ which sounded far more dangerous than the ‘Matilda’ and ‘Valentine’ of the British army. They had fast E-Boats, pocket battleships, rockets and jet-engined aircraft for goodness sake. By the early Sixties, thanks to films and comics, schoolboys knew exactly what was meant when a character in a thriller appears armed with ‘a Schmeisser’ 9– the sub-machine gun as synonymous with the Nazis as the Thompson ‘Tommy Gun’ had been seen as the weapon of choice of Chicago gangsters in the Thirties. Plastic toy soldiers, Dinky and Corgi toy military vehicles and Airfix scale-model kits made sure that young males were totally familiar with the paraphernalia of the European war; less so with the war in the Pacific and the staggering scale of the Russians’ contribution to WWII hardly figured at all.

Thriller writers quickly realised that if their plots struck a familiar resonance with the war, they would find ready acceptance among a young male readership. Their characters would be very straightforward: they would be male of course, and in the main British (though Canadian or a New Zealander might be allowed) as, after all, the British had won the war, hadn’t they? And the plot possibilities seemed endless: revenge and the settling of old scores, bringing war criminals to justice, reclaiming stolen treasure, uncovering treachery, revealing Byzantine espionage conspiracies, and secrets thought safely buried by governments.

When he turned to writing novels after a decade of success as a radio and television dramatist, Berkely Mather set his first thriller, The Achilles Affair (1959), in the Eastern Mediterranean with a detailed back-story (almost a third of the book) involving the wartime resistance in Greece. In 1963, a writer who was to become possibly the closest to rival Alistair MacLean in the adventure thriller stakes, Desmond Bagley, made his debut with The Golden Keel , a sea-going tale of modern piracy which involved smuggling Mussolini’s personal treasure, lost during the war, out of Italy. Indeed, the Sunday Times said of newcomer Bagley that The Golden Keel ‘catapults him straight into the Alistair MacLean bracket’. Another thriller-writing talent coming into full bloom at the same time was Gavin Lyall and his highly regarded third novel Midnight Plus One in 1965 harks back to the ‘rat lines’ and escape routes used by the French Resistance during WWII. Even that rather more ephemeral talent and the epitome of Swinging Sixties London, Adam Diment, had former Nazis at the core of the plot of The Dolly, Dolly Spy in 1967, 10and Diment’s very modern hero, the rebellious, ultra-hip, pot-smoking Philip McAlpine toted a trusty ‘Schmeisser’ as his weapon of choice.

If memories or hangovers from the Nazi-era were not enough, some thriller writers invented hereditary threats in the form of biological, rather than ideological, children of Adolf Hitler. 11.Both Victor Canning and John Gardner speculated on Hitlerite off-spring in, respectively, The Whip Hand (1965) and Amber Nine (1966), and again in Gardner’s The Werewolf Trace (1977).

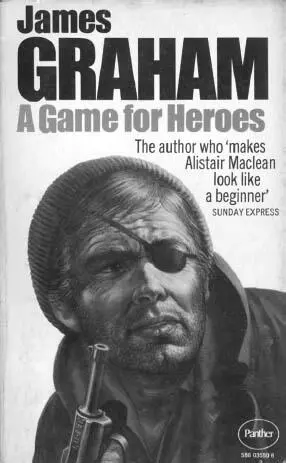

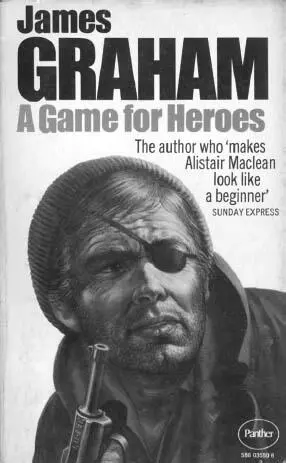

A Game for Heroes , Panther, 1971

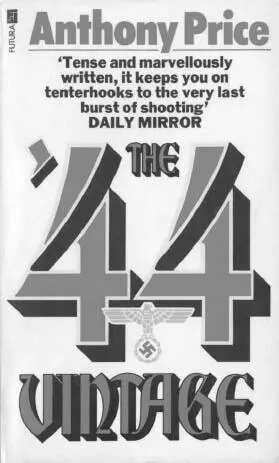

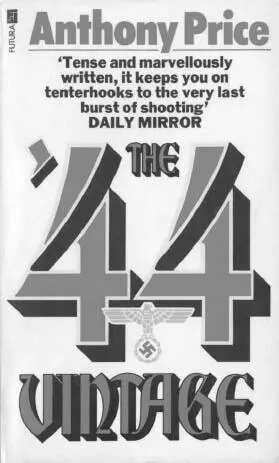

The ’44 Vintage , Futura, 1979

Yet wartime settings never ever went out of fashion. For thriller writers in the 1960’s and ’70’s, ‘don’t mention the war’ was definitely counter-productive advice. Alistair MacLean was to revisit the war years several times, most notably in 1967 with Where Eagles Dare. Before he hit the jackpot with The Eagle Has Landed , Jack Higgins – writing as James Graham – produced A Game for Heroes in 1970, an exceptional thriller set on an imaginary Channel Island in 1945. The Sunday Express proclaimed the author as one who ‘makes Alistair MacLean look like a beginner’, but it was to be another five years before the eagle actually landed for Jack Higgins and he was able to move to the less onerous tax regime of a real Channel Island. In 1974, Clive Egleton scored with a convoluted scheme to assassinate Hitler’s Deputy, Martin Bormann, in The October Plot , and in 1978 Duncan Kyle presented an even more complicated scenario surrounding a suicidal commando raid on Heinrich Himmler’s spiritual home of the SS, Wewelsburg Castle, in Black Camelot . One of the leading spy-fiction writers of the 1970s, Anthony Price even provided a stunning wartime backstory for his contemporary spy hero Dr David Audley in The ’44 Vintage in 1978.

It should not be surprising that the war was a popular topic with writers (and by extension: agents, editors, publishers, and readers) as at least a third of the British thriller writers in the boom period of the Sixties and Seventies had seen active service during WWII.

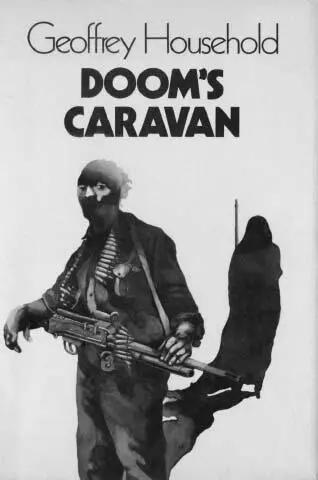

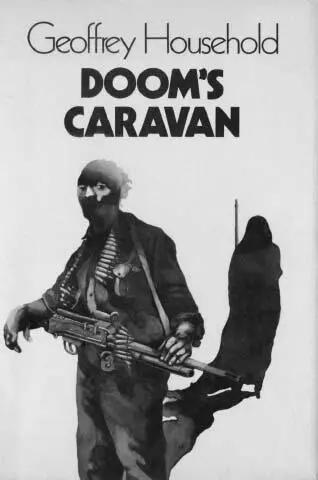

In many cases, the wartime experiences of these authors were stranger than any fiction they produced, but writers being writers, few life experiences were wasted. Miles Tripp, a noted crime writer who experimented with Bond-like thrillers under the pen-name John Michael Brett, flew thirty-seven sorties as a bomb-aimer with the RAF during WWII and his first novel about the crew of a Lancaster bomber, Faith Is a Windsock in 1952, was clearly semi-autobiographical. Berkely Mather – an old ‘India hand’ with considerable (and colourful) military experience in the Far East – certainly knew of what he wrote when he penned his bestselling The Pass Beyond Kashmir (1960) and the piratical treasure-hunt adventure thriller The Gold of Malabar (1967). Geoffrey Household, for whom the Second World War had started early and very unofficially in ‘neutral’ Romania, then served in Field Security in the Middle East for the best part of five years, which provided background for his 1971 thriller Doom’s Caravan, set on the border between Lebanon and Syria. Household was also affected by his experience at the very end of the war when he was with a British army unit liberating the Nazi concentration camp at Sandbostel 12near Hamburg, which he later described as ‘beyond experience or imagination’. Antony Melville-Ross (who was to create the only secret agent in fiction called Alaric) was a highly successful and highly decorated Royal Navy submarine commander and Lionel Davidson, who was to write some iconic thrillers, served in submarines in the Indian Ocean for most of the war, though much against the trend in adventure thrillers of the period, a submarine never featured in his fiction.

Doom’s Caravan , Michael Joseph, 1971, design by Richard Dalkins

Even when the cinema box office turned away from the war film and embraced the spy film after 1962, the Second World War continued to influence British thriller writing and indeed still does; as in the work of contemporary writers Philip Kerr (1956–2018), John Lawton, David Downing, Laura Wilson and Paul Watkins (also writing as Sam Eastland). Nazi Germany and WWII has figured widely in the work of novelist Robert Harris, who was born in 1957, not least in his debut thriller Fatherland . In 2017, whilst promoting his new novel Munich , he was asked why the Nazis were still a popular subject for British thriller writers – and readers. ‘The Nazis,’ he said, ‘are like a planet with a gravitational pull.’ 13

Читать дальше