If these bones belonged to humpback whales, it would not be surprising, given the abundance of this species out around Antarctica today. It’s likely that some of the whales that we tagged were descendants of these individuals, belonging to the same genetic lineage. But history tells us that if you turned back the clock a century, humpbacks probably wouldn’t have been the only ones here: blue and fin whales would have numbered in the hundreds, if not thousands; minke whales, beaked whales, and even Southern right whales would also have been part of the community. Ari has seen only one right whale out of the thousands of whales that he’s observed over fifteen years in the area. Southern right whales have barely recovered from two hundred years of whaling, and we know little about where they go besides their winter breeding grounds along protected coastlines of Australia, New Zealand, Patagonia, and South Africa.

It’s not just right whales that vanished. There’s no memory or record of just how many of any kind of whale there was in the Southern Ocean, in terms of their abundance, before twentieth-century whaling killed over two million in the Southern Hemisphere alone. However, as whale populations in this part of the world slowly recover from this devastation, we’re beginning to see what that past world might have looked like. On an expedition in 2009, Ari and his colleagues documented an extraordinary aggregation of over three hundred humpbacks in Wilhelmina Bay, the largest density of baleen whales ever recorded. “There is no external limit on these whales because there is just so much krill. They literally cannot eat enough before they need to leave,” Ari reflected. “That incredible resource base means that it’s just a matter of recovery time for whales—and I think what we saw in the bay that year was a glimpse of what their world was once like, before whaling.” On the whole, humpbacks have recovered to only about 70 percent of their prewhaling numbers in the Southern Ocean, although along the peninsula their population size has nearly returned to the best estimates of prewhaling levels at the start of the twentieth century.

I paused on a guano-free ledge to record a few observations about the bones’ weathering and their measurements in my field notes. To the southwest, the sky churned in a dark gray, portending wind and snow, and I felt a chill creep into my damp toes and fingertips. I pulled off my gloves and reached for a disposable hand warmer in my jacket pocket. Lodged in a mess of receipts and lozenge wrappers was a note my son had left me on the kitchen counter back home:

Im gona mis you

wen you go to

anaredica.

The night before I left my home in Maryland we traced the expedition route on a plastic globe. When he wanted to know how far away eight thousand miles was in inches, I didn’t tell him the answer that I wanted to, which was “Too far.” I reassured him that the passage was safe and that we would stay warm. “I’ll think about you when we drink hot cocoa,” I offered, dressing up my own concerns with a good smile.

As we pulled away from Cuverville Island to return to the Ortelius , the swirling clouds began to send down flurries, covering us in thick, wet snow. The boat bumped hard against the waves, and we saw humpbacks surfacing far off in the distance, the wind pushing their blows quickly behind them. The sight of those living, breathing, feeding whales in the same view as the island with beach-cast bones made me feel as though I could see the present and past simultaneously, each telling us facts that the other vantage could not. The bones on Cuverville Island and Ari’s tagging work in the Gerlache were each a unique window into the story of humpback whales in the Antarctic, though these views were terribly incomplete: the past represented by mere bones crumbling on remote shores, what we know today limited to a few hours’ or days’ worth of data collected by a hitchhiking recorder on whales’ backs.

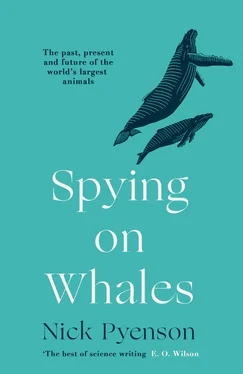

Scientists tend to operate within intellectual silos because of the years of training and study that it takes to know about any single part of the world. But the best questions in science arise at the edges. Ari and I both want to know how, when, and why baleen whales evolved to become giants of the ocean—Ari wants to know more about their ecological dominance today, and I want to know what happened to them across geologic time. The answer to the basic question about the origin of whale gigantism requires pulling data and insights from multiple scientific disciplines, which is another way of saying that we need the perspectives of different kinds of science—and scientists—to untangle the monstrous challenges of the nearly inaccessible lives of whales. That’s why a paleontologist like me was on a boat tagging whales at the end of the Earth: I needed a front-row seat to know exactly what we can hope to know from a tag. But answering the questions that most captivate me about whales requires more than just a single tag. It means wrapping my arms around museum specimens, handling microscope slides, paging through century-old scientific literature, and wading knee-deep in carcasses.

The wind sapped the last warmth from my already-wet gloves and whipped through openings around my hood as I held tight to the ropes on the gunnels. The first scientists to visit this place, over a hundred years ago, didn’t have the luxury of disposable hand warmers. They suffered more brutally than we can really imagine, with less certainty of safe return. In these narrow margins they must have wrestled with the tension that overcomes scientists in the field: the desire to apprehend something almost unknowable against the tolls of living a world away from civilization. I patted my son’s note, folded safely inside my jacket pocket. Hot cocoa sounded just right.

I was never a whale hugger. I didn’t fall asleep snuggling stuffed whales or decorate my room with posters of humpbacks suspended in prismatic light. Like most children, I went through phases of intense study: sharks, Egyptology, cryptozoology, and paleontology. The curriculum was loosely inspired by my small curio cabinet crammed with a bric-a-brac collection of gifts and found treasures: abalone shells from my parents’ friends in California and fluorite from a great-aunt in New Mexico sat next to trilobites and fossil ferns that I had collected on family trips to Tennessee and Nova Scotia (good fossils being hard to come by on the island of Montreal). My collection was a tangible means to escape, across geography and time, as I read ravenously about dinosaurs, mammoths, and whales under the tacit encouragement of my parents, professors who recognized this type of aimless curiosity.

During one of my immersive phases, I came across a distribution map that showed the location of whale species around the world. With my finger I traced the range of blue whales, the largest of all whales, as it went right up the St. Lawrence River, which bordered my neighborhood. I wondered about my chances of seeing a blue whale casually surfacing in the distance near my house. The thought of a local blue whale was a reverie that often arose in my mind as a kid, although it took two decades for me to return to it in earnest, as a scientist.

Some branches on the tree of life become quite personal, for reasons that are difficult to explain. We seek reflections of parts of ourselves in beings seemingly close to us—the disdain of a house cat or the perseverance of a tortoise—but in the end these species are distinctly other, refashioned by evolution and eons of time away from our shared ancestry. Those differences are accentuated to the furthest degree in whales; they seem mostly other—otherworldly, really—and that makes them both fascinating and enigmatic. They embody an incongruity that is vexing because they betray their mammalian heritage in so much of what they do, yet they look and live so far apart from us. Their size, power, and intelligence in the water are astonishing because they’re unparalleled, yet whales are benign and pose no threat to our lives. They are almost a human dream of alien life: approachable, sophisticated, and unscrutable.

Читать дальше