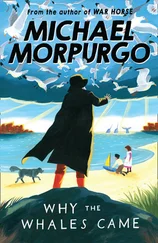

This book is not a synoptic, comprehensive account of every different species of whale—there are far too many whales to fit into anything shorter than an encyclopedia. Instead, this book presents a selective account, a kind of travelogue to chasing whales, both living and extinct. I describe my experiences from Antarctica to the deserts in Chile, to the tropical coastlines of Panama, to the waters off Iceland and Alaska, using a wide variety of devices and tools to study whales: suction-cupped tags that cling to their backs; knives to dissect skin and blubber from muscles and nerves; and hammers to scrape and whack away rock that obscures gleaming, fossilized bone.

The narratives in this book group into three general sections: past, present, and future. Broadly, I want to answer questions about where whales came from, how they live today, and what will happen to them on planet Earth in the age of humans (a new era that some scientists call the Anthropocene). But these stories don’t cleanly fit into these three temporal silos. Instead, they build on one another and reciprocate because the ways that we need to think about whales require thinking about all the evidence at hand: unraveling the many mysteries of living whales requires a background about their evolutionary past, just as much as the surprises from the fossil record can clarify the meaningful facts about their lives today and into the future.

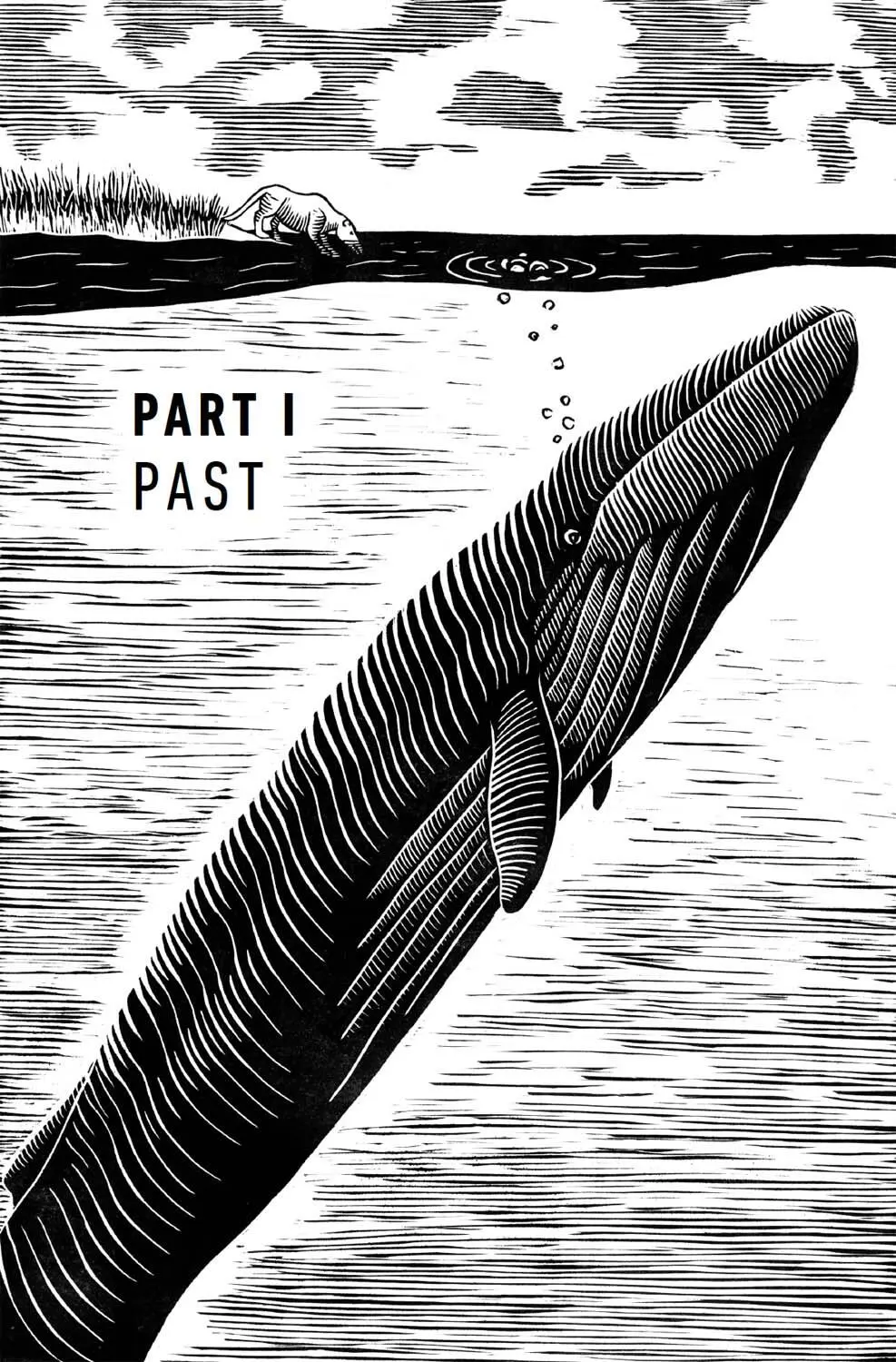

The first part of the book tells the chronicle of how whales went from walking on land to being entirely aquatic, relying on evidence from the fossil record showing what the earliest whales looked like. These fossils show us details that we couldn’t otherwise know about the history of whales, and I explore exactly how we dig up these clues in the first place. Following fossil whale bones brought me to the Atacama Desert of Chile, where my colleagues and I puzzled over an ecological detective story with the discovery of Cerro Ballena, the world’s richest fossil whale graveyard. How did this site come about, and what does it tell us about whales in geologic time?

The second part examines how and why whales became the biggest creatures ever in the history of life. The challenges of studying organisms as large as the largest species of whales means thinking about the limits of biology, and what exactly organisms at these superlative scales need to do, on a daily basis, to sustain their enormous sizes. While trying to connect muscle to bone at a whaling station, I share another serendipitous find: the discovery of an entirely new sensory organ in whales. What does an organ, lodged right at the tip of a whale’s chin, mean for how, when, and why baleen whales evolved to become all-time giants?

Lastly, the third part explores the specter of the uncertain future that we share with whales on Anthropocene Earth. In the twentieth century alone, whaling in the open oceans killed more than three million whales, reducing many populations to shadows of their baseline abundances. Despite this decimation, no single species went extinct until the first decade of the twenty-first century. Since then, not a whistle or splash of the Yangtze river dolphin has been recorded, and responsibility for the extinction of this species can be placed squarely on our shoulders: we dammed the only river in which it lived. Other species, such as the vaquita, remain on the extinction watch list, numbering fewer than one dozen or two dozen individuals. But the news from the field isn’t entirely dire: some whale species have rebounded from the brink, even expanding to new habitats as climate and oceans change. What can we imagine about our shared future with whales, drawing on their lives today and what we know about their evolutionary past?

Ultimately, the quest to understand whales is a human enterprise. This book is a story not just about knowing whales but also about the scientists who study them. The scientists described in these stories come from a variety of different disciplines, ranging from cell biology and acoustics to stratigraphy and parachute physics. Some are historical but very much knowable through their writings, their specimen collections, and the intellectual questions that they asked. One of the great privileges of my professional life is the opportunity to work at the Smithsonian, which has afforded me not only the latitude to undertake this pursuit but also firsthand access to some of the world’s largest and most important collections of material evidence, be it specimens, scientific journals, or unpublished field notes. Every day, I think about the many generations of scientists before me who handled this same evidence, scratching away at the very same questions, while constrained by the circumstances of their times. My hope is that this book says as much about the inner lives of scientists as it does about whales.

I sat transfixed by a sea littered with a million fragments of ice, all rising and falling in time with the slow roll of the waves. We had spent the morning looking for humpback whales in Wilhelmina Bay, threading our rubber boat between gargantuan icebergs that were tall and sharp, like overturned cathedrals. Now we stopped, cut the engine, and listened in the utter stillness for the lush, sonorous breath of an eighty-thousand-pound whale coming to the water’s surface. That sound would be our cue to close in. We had come to the end of the Earth to place a removable tag on the back of one of these massive, oceangoing mammals, but we took nothing for granted in Antarctica. As we sat waiting on the small open boat, I came to feel more and more vulnerable, a speck floating in a sea of shattered ice. “Don’t fall in,” my longtime collaborator and friend Ari Friedlaender deadpanned.

I struggled to remember how long we had been away from the Ortelius , our much larger oceanic vessel with its ice-hardened steel hull. In every direction, we were enclosed by a landscape of nunataks, jagged spires of rock that pierced the creamy tops of surrounding glaciers. Where the glaciers met the sea, they ended in sheer, icy cliffs towering over the bay. Without a human structure for scale, these landforms seemed both near and far at the same time. This otherworldly scene of ice, water, rock, and light warped my sight lines, bending my sense of distance and the passage of time.

If you hold your fist with your left thumb out, your thumb is the western Antarctic Peninsula; your fist, the Antarctic continent’s outline. The Gerlache Strait is part of a long stretch of inner passageway along the outer side of Antarctica’s left thumb, and Wilhelmina Bay cuts a rough cul-de-sac off the Gerlache. The Gerlache is a hot spot for whales, seals, penguins, and other seabirds, and Wilhelmina Bay is the bull’s-eye. All come here to hunt for krill, small crustaceans that form the centerpiece of Antarctic ocean food webs. Consider your hand again: individual krill are about the length of your thumb, but whales pursue them because they explode into great aggregations, or swarms, during the Antarctic summer. With the right mixture of sunlight and nutrient-rich water, dense clouds of krill form a sort of superorganism that can stretch for miles and concentrate in hundreds of individuals per cubic foot. By some measures, there is more biomass of krill than of any other animal on the planet. Calorie-rich swarms of them lurked somewhere, not far, just under our boat.

Where there are krill in sufficient quantities, there will be whales, but the fundamental problem with studying whales is that we almost never see them, except when they come to the surface to breathe or when we dive, in our own limited fashion, in search of them. Whales are inherently enigmatic creatures because the parameters of their lives defy many of our tools to measure them: they travel over spans of whole oceans, dive to depths where light does not reach, and live for human lifetimes—and even longer.

Читать дальше