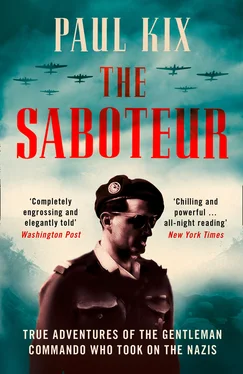

La Rochefoucauld explained how he’d gotten to London, and “de Gaulle first complimented me on wanting to join the Free French forces,” Robert wrote. La Rochefoucauld then said that the British had intervened and asked him to join its clandestine service; he wasn’t yet clear on the details, but that’s why he had come to see de Gaulle. He had only wanted to work under the general, but now he wondered: Should he join this secret British organization?

De Gaulle had a complicated and contentious relationship with the Brits. He demanded autonomy and yet relied on Britain financially to train and equip his troops. He needed to be diplomatic with London to achieve his ends but, to appeal to Frenchmen as the true voice of France, needed to undercut his diplomacy, too. “He had to be rude to the British to prove to French eyes that he was not a British puppet,” Churchill wrote. “He certainly carried out this policy with perseverance.” Churchill loved and loathed him. The romantic in Churchill saw a rebel and great adventurer in de Gaulle, “the man of destiny.” But the general’s incorrigible rudeness and unending demands on behalf of a sovereign nation that was, in truth, occupied by the Nazis, drove Churchill mad. Over the course of the war the prime minister went from wondering if de Gaulle had “gone off his head,” to calling him a “monster,” to saying he should be kept “in chains.” Franklin Roosevelt didn’t like him any better. The United States president gave de Gaulle all of three hours’ notice before the Allies’ massive 1942 landings in French-controlled Algeria and Morocco.

De Gaulle didn’t get along well with the British intelligence services, either. His Free French staff initially believed Piquet-Wicks and other Brits were poaching would-be French agents. Some Free French staffers thought of the British as a “rival organization,” Piquet-Wicks wrote. But in time certain spies in London saw the benefit of working with de Gaulle—nearly every Frenchman who came to the city wanted to meet him—and so Piquet-Wicks’s division began sharing information, and then missions, with the intelligence bureau of the Free French. Loyalties blurred, and many secret agents Piquet-Wicks oversaw considered themselves to be working first for de Gaulle, and the operatives’ success in France drew more people to London, which in turn strengthened the general, militarily as well as politically.

Now, weighing La Rochefoucauld’s question of joining the British, de Gaulle peered again at the young man, until he reached a conclusion that Robert would remember for the rest of his life: “It’s still for France,” de Gaulle said, “even if it’s allied with the Devil. Go!”

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.