1 ...6 7 8 10 11 12 ...29 Unsurprisingly, the group psychology of families—relations between husbands and wives, the interactions of parents and children—is fraught in Goreyland. Parents are absent or hilariously absentminded, like Drusilla’s parents in The Remembered Visit , who, “for some reason or other, went on an excursion without her” one morning and never returned. Of course, neglectful parents are vastly preferable to the heartless type, a more plentiful species in Gorey stories. In The Listing Attic , we meet the “headstrong young woman in Ealing” who “threw her two weeks’ old child at the ceiling … to be rid of a strange, overpowering feeling”; the Duke of Daguerrodargue, who orders the servants to dispose of the puny pink newborn that nearly killed his wife in child-birth; and the “Edwardian father named Udgeon, / whose offspring provoked him to dudgeon,” so much so that he’d “chase them around with a bludgeon.”

Kids growing up in households where adults are inscrutable and unpredictable learn that keeping their mouths shut and their expressions blank is the shortest route to self-preservation. (Burying your nose in a book is another way of making yourself invisible.) Gorey’s people are almost entirely expressionless, their mouths tight-lipped little dashes; they barely make eye contact and shrink from displays of affection. Conversation consists mostly of non sequiturs; awkward silences hang in the air. Alienation and flattened affect are the norm.

The only truly happy relationships in Gorey’s books are between people and animals: Emblus Fingby and his feathered friend in The Osbick Bird , Hamish and his lions in The Lost Lions , Mr. and Mrs. Fibley and the dog they regard as a surrogate child when their infant disappears from her cradle in The Retrieved Locket . None of which is at all surprising: Gorey’s fondness for his cats was at least as deep as his affection for his closest human friends, probably deeper. Asked by Vanity Fair , “What or who is the greatest love of your life?” he replied, “Cats.” 18Perhaps the warmest bonds are between animals, as in The Bug Book , the only Gorey title with an unequivocally happy ending. In it, a pair of blue bugs who live in a teacup with a chip in the rim are “on the friendliest possible terms” with some red bugs and yellow bugs, calling on each other constantly and throwing delightful parties. They’re all cousins, of course.

In 1931, another not entirely ordinary incident ruffled the placid surface of Gorey’s “perfectly ordinary” childhood. He was six, but his precociousness enabled him to skip first grade and enroll as a second grader. The school in question was a parochial school; Gorey had been baptized Catholic. Saint Whatever-It-Was (no one knows which of Chicago’s parochial schools he attended) was loathe at first sight. “I hated going to church and I do remember I threw up once in church,” he recalled. “I didn’t make my First Communion because I got chicken pox or measles or something and that sort of ended my bout with the Catholic church.” 19

The temptation to see Gorey’s suspiciously well-timed illness as a verdict on the faith is tempting, especially in light of his terse response to the question, “Are you a religious man?”: “No.” 20His brief spell in Catholic school didn’t leave him with the usual psychological stigmata, he claimed—“I’m not a ‘lapsed Catholic’ like so many people I know who apparently were influenced forever by it”—but it does seem to have put him off organized religion for good. 21

A subtle anticlerical strain runs through Gorey’s work: cocaine-addled curates beat children to death, nuns are possessed by demons, unfortunate things happen to vicars. In Goreyland, immoderate religiosity is soundly punished: Little Henry Clump, the “pious infant” of Gorey’s 1966 book of the same name, is pelted by giant hailstones, succumbs to a fatal cold, and lies moldering in his grave, all of which make the narrator’s assurance that Henry has gone to his reward sound like a laugh line for atheists. Saint Melissa the Mottled , a book Gorey wrote in 1949 but never got around to illustrating (Bloomsbury published it posthumously, with images filched from his other books), is a gothic hagiography about a nun noted not for good works but for Miracles of Destruction. Given to dark designs involving blowgun darts, Melissa graduates, in time, to “supernatural triflings” such as the withering of the Duke of Dimgreen’s arm and a seagull attack on two young girls. In death, she becomes the patron saint of ruinous randomness. She’s just the sort of saint you’d dream up if you believed, as Gorey did, that “life is intrinsically, well, boring and dangerous at the same time. At any given moment the floor may open up. Of course, it almost never does; that’s what makes it so boring.” 22

In fact, the floor was always opening up in Gorey’s early years.

For example, after his less-than-successful year in parochial school, his parents sent him to Bradenton, Florida, a small city between Tampa and Sarasota, to live with his Garvey grandparents for the following year.

Why? It is, as they say in Catholic theology, a Mystery.

In the fall of ’32, he entered third grade in Bradenton, at Ballard Elementary. He seems to have landed on his feet, catlike, in alien surroundings: he made new friends, had a dog named Mits, was a devoted reader of the newspaper strips (“I get all the Sunday funnies, but I want you to send down the everyday ones,” he wrote his mother), and earned high marks on his schoolwork. 23

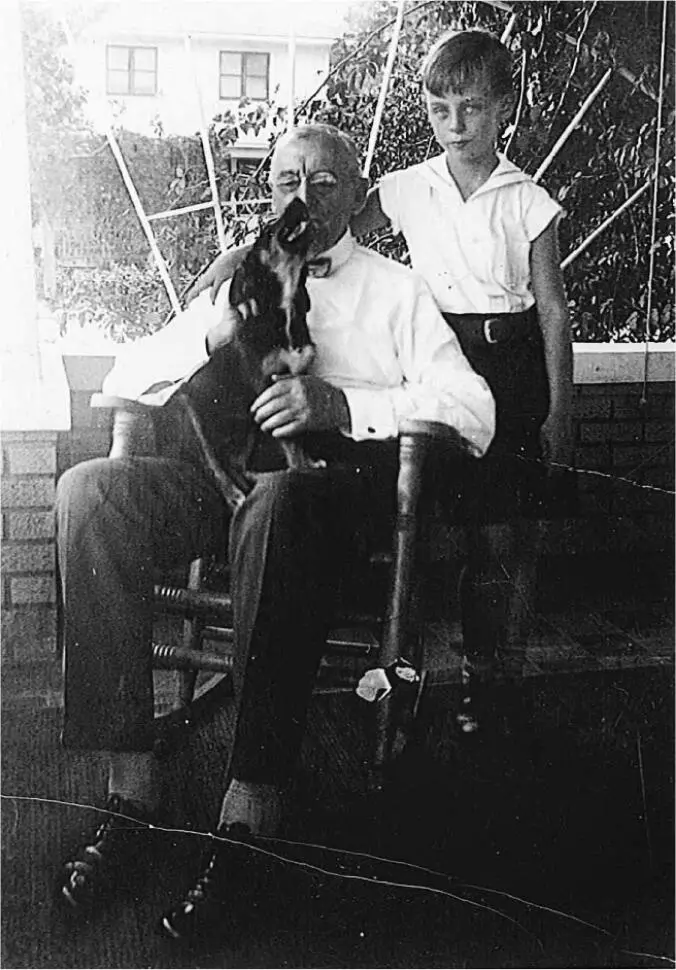

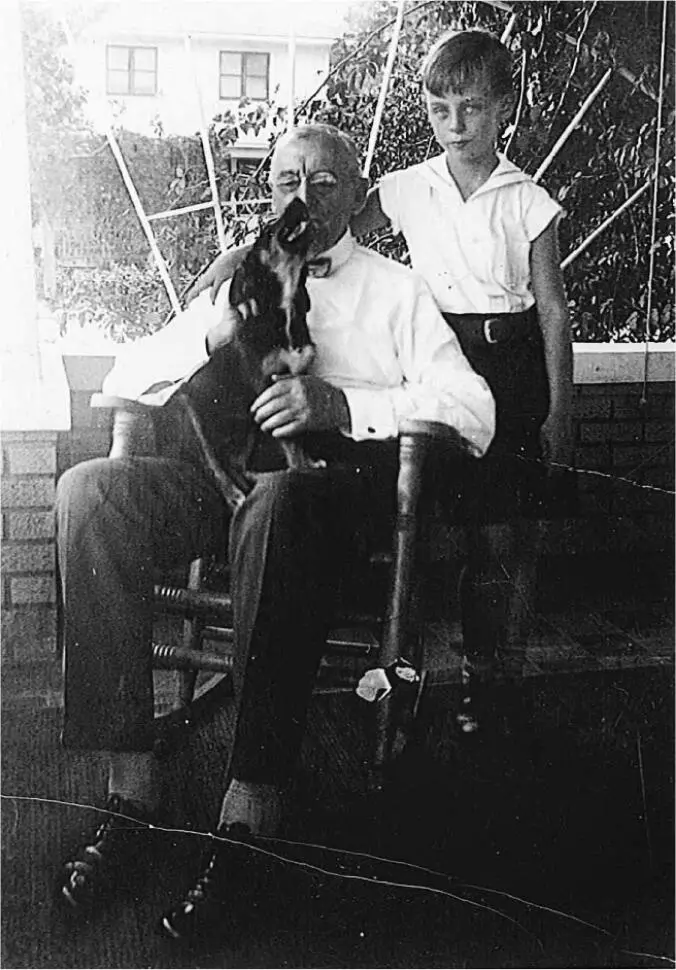

But a December 1932 photo of him with his grandfather Benjamin Garvey tells another story. Sitting in a rocker on what must have been the Garveys’ porch or patio, the old man gazes benignly, through wire-rimmed glasses, at the dog on his lap, petting him; Mits—it must be Mits—arches his back in an excess of contentment. Ted stands behind him, a proprietary hand on his grandfather’s shoulder. He regards us with the same penetrating gaze, the same unsmiling mien we see in his posed photos as an adult. It is, to the best of my knowledge, the only picture of Gorey touching someone in an obvious gesture of affection.

Gorey, age seven, in Bradenton, Florida, with his maternal grandfather, Benjamin S. Garvey, December 1932. (Elizabeth Morton, private collection)

Returning to Chicago in May of ’33, eight-year-old Ted was packed off to something called O-Ki-Hi sleepaway camp, an “awful” experience he managed to survive by spending all his time “on the porch reading the Rover Boys.” 24

Clearly there was more than enough unpredictability and inexplicability in his world to inspire his life’s goal, as an artist, of making everybody “as uneasy as possible, because that’s what the world is like.” “We moved around a lot—I’ve never understood why,” he told an interviewer when he was sixty-seven. “We moved around Rogers Park, in Chicago, from one street to another, about every year.” 25By June of 1944, when he left Chicago for his army posting to Dugway Proving Ground, outside Salt Lake City, he’d called at least eleven addresses home: two in Hyde Park, five in Rogers Park, two in the North Shore suburb of Wilmette, one in the city’s Old Town neighborhood (in the Marshall Field Garden Apartments), and one in Chicago’s Lakeview community. 26He’d been bundled off to Florida twice, the second time to Miami, where in 1937 he attended Robert E. Lee Junior High, returning to Chicago for the summer of ’38. All told, he’d gone to five grammar schools by the time he enrolled in high school.

Читать дальше