No less important for a budding visual intelligence were the illustrations in the books he read as a child. “We [had] a wonderful horrid thing called Child Stories from Dickens , which was illustrated with chromolithographs,” he recalled. “It was all the deaths: Little Nell, [Smike] from Nicholas Nickleby . I remember it with horror.” 7

He fell in love with Ernest Shepard’s wry, fine-lined drawings for A. A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh and the sharp-nibbed precision of Tenniel’s illustrations for the Alice books. Little wonder, then, that he grew up to be the sort of artist who is all about line. “Line drawing is where my talent lies,” he said in a 1978 interview. 8What strikes the eye before anything else, in Gorey’s work, is his mesmerizing pen-and-ink technique. Look close, and you can almost see the pullulation of a million little strokes. You’ve seen this texture somewhere before, the tight mesh of crisscrossed lines. And then it hits you: the man is doing hand-drawn engraving . What you’re looking at, in all that impossibly uniform stippling and cross-hatching, is the fastidious mimicry, by hand, of effects usually achieved with engravers’ tools: gravers, rockers, roulettes, burnishers. Gorey is a counterfeiter of sorts, fooling us into thinking his drawings are engravings, obviously of Victorian or Edwardian vintage, undoubtedly by an Englishman long dead.

According to Gorey, “the Victorian and Edwardian aspect” of his work had its origins in “all those 19th-century novels I’ve read and [in] 19th-century wood engraving and illustration.” 9But there was a more elusive quality that seduced him as well, “the strange overtone” nineteenth-century illustrations have taken on over time. 10The Victorian era bore witness to the birth of the mass media, inundating British society with a flood of mass-produced images. Many of those images are still floating around, in one form or another, and Gorey was drawn to the uncanniness of all those transmissions from a dead world—specifically, to their unsettling combination of coziness and creepiness, which Freud called the unheimlich (literally, “unhomelike”).

It was that same quality, he thought, that seduced the surrealist artist Max Ernst, who with the aid of scissors and paste conjured up dreamlike vignettes from Victorian and Edwardian scientific journals, natural-history magazines, mail-order catalogs, and pulp literature. Gorey was profoundly influenced by Ernst’s wordless, plotless “collage novels,” of which Une Semaine de Bonté (A week of kindness, 1934) is the best known. Seamlessly assembled from black-and-white engravings, Ernst’s images look like scenes from silent movies shot on some back lot of the unconscious: a bat-winged woman weeps on a divan, oblivious to the sea monster beside her; a tiger-headed man brandishes a severed head, fresh from the guillotine. “I was very much taken with [nineteenth-century illustrations], in the same way that I presume Max Ernst was,” said Gorey. “I mean, all those things that Ernst used in his collages can’t have looked that sinister to people in the 19th century who were just leafing through ladies’ magazines and catalogues. And, of course, now they look nothing but sinister, no matter what. Even the most innocuous Christmas annual is filled with the most lugubrious, sinister engravings.” 11

Gorey started drawing even earlier than he started reading, at the age of one and a half. 12“My first drawing was of the trains that used to pass by my grandparents’ house,” he remembered. 13Benjamin St. John Garvey and Prue (as Ted’s stepgrandmother, Helen Greene Garvey, was known to the family) lived in Winthrop Harbor, an affluent suburb north of Chicago on the shores of Lake Michigan. Their house was on a bluff, overlooking the Chicago and North Western railroad tracks. Describing his infant effort, he recalled, “The composition was of various sausage shapes. There was a sausage for the railway car, sausages for the wheels, and little sausages for the windows.” 14

Gorey, who saw much more of his mother’s side of the family than he did his father’s, seems to have had fond memories of his visits to Winthrop Harbor: family photos show him squatting by an ornamental pond, peering at a flotilla of lily pads; trotting alongside his grandfather as he mows the lawn.

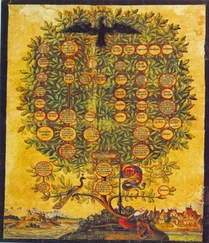

All of which has the makings of what Gorey assured interviewers was a disappointingly “typical sort of Middle-Western childhood.” 15Before his birth, however, his grandparents starred in a gothic set piece—a messy divorce—that must have scandalized the Garvey clan, especially since the Chicago papers gave it front-page play. (Benjamin was vice president of the Illinois Bell Telephone Company, and his marital melodrama made good copy.) Whether any sense of things hushed up crept into the corners of Gorey’s consciousness, we don’t know, though it’s tempting to locate the sense of things repressed that pervades his work—the furtive glances, the averted gazes—in the grown-ups’ whisperings about scenes played out behind closed doors.

Gorey’s grandmother Mary Ellis Blocksom Garvey had divorced his grandfather in 1915; it was the unhappy denouement of a marriage buffeted by accusations of madness and counteraccusations of forced stays in sanitariums, where Gorey’s grandmother was restrained in a strait-jacket and left to languish in solitary confinement, she claimed. “tried to drive me insane,” wife asserts in suit, the Chicago Examiner blared. phone man kept her in sanitarium until reason fled, she declares. 16

The divorce sowed discord among the Garvey children. Ted’s cousin Elizabeth Morton (known by her nickname Skee *) remembers him talking about his mother and her siblings fighting. Skee’s sister, Eleanor Garvey, thinks “it was a fairly volatile family.”

Asked by an interviewer if he was an only child, Gorey said, “Yes. And in childhood I loved reading 19th-century novels in which the families had 12 kids.” 17Then, in the next breath: “I think it’s just as well, though, that I didn’t have any brothers or sisters. I saw in my own family that my mother and her two brothers and two sisters were always fighting. There were so many ambivalent feelings. And then my grandmother would go insane and disappear for long periods of time.” (Madness and madhouses recur throughout Gorey’s work: an asylum broods on a desolate hill in The Object-Lesson ; the protagonists of The Willowdale Handcar spy a mysterious personage who may or may not be the missing Nellie Flim “walking in the grounds of the Weedhaven Laughing Academy”; Madame Trepidovska, the ballet teacher in The Gilded Bat , loses her reason and “must be removed to a private lunatic asylum”; Jasper Ankle, the unhinged opera fan who stalks Madame Caviglia in The Blue Aspic , is “committed to an asylum where no gramophone [is] available”; Miss D. Awdrey-Gore, the reclusive mystery writer memorialized in The Awdrey-Gore Legacy , may or may not have gone to ground in “a private lunatic asylum”; and on and on.)

In later life, Gorey adopted Eleanor and Skee as surrogate siblings. “I felt as if I were his little sister,” says Skee. “Since we never had a brother, and he never had any siblings …” She trails off, the depth of feeling in her voice unmistakable. “I think that’s why he liked being here, ’cause it was like having sisters,” she decides. (By “here,” she means Cape Cod, where Gorey spent summers with his Garvey cousins from 1948 on, moving there for good in 1983.) Cousins are the most frequent familial relations in Gorey’s stories; make of that what you will.

The childhood Gorey insisted was “happier than I imagine” was troubled by tensions in his parents’ marriage, too. Class frictions between the Garveys’ aspirational WASPiness and the Goreys’ cloth-cap Irishness complicated things. Who knows how Ted negotiated the transition from his well-heeled grandparents’ suburban idyll, in Winthrop Harbor, to the corner-pub world of his Gorey relatives?

Читать дальше