1 ...8 9 10 12 13 14 ...29 As of June ’36, the Goreys had moved across town to the Linden Crest apartments at 506 5th Street, a block from the 4th and Linden El stop.

That September, Ted enrolled in the eighth grade at a nearby junior high, the Byron C. Stolp School, a shorter walk from his new address than Howard. Gorey, famously not a joiner as an adult, was the quintessential joiner in junior high: alongside his photo in the 1936–37 edition of the Stolp yearbook, Shadows , he’s listed as assembly president as well as a member of the typing club, the Shakespeare club, the glee club, and, not least, the art club.

Gorey’s art teacher at Stolp was Everett Saunders, a former WPA painter and dedicated mentor to would-be artists. Saunders oversaw the art club, whose ranks included Warren MacKenzie and, improbably enough, Charlton Heston. MacKenzie would grow up to be a master potter whose Japanese-influenced clayware is prized for its understated beauty. Now ninety, he remembers Heston as “a real poser,” a characterization confirmed by Heston’s Stolp yearbook photo, in which the man who would be Moses, sporting a budding pompadour, gives the camera an eighth grader’s idea of a smoldering gaze. (What can it mean that “Gorey always claimed with a straight face,” according to his friend Alexander Theroux, that “Charlton Heston was ‘the actor of our time’”?) 40

MacKenzie, who coedited the 1937 Shadows , recalls Gorey’s “really funny” cartoons for the yearbook’s club pages. Ted executed nine full-page line drawings, among them a picture of a cat in an artist’s smock and beret holding a palette and a dripping paintbrush (for the art club); a cat in an eyeshade, sweating bullets, up against a deadline from hell (for the journalism club); and a feline Romeo in a Renaissance cape, tearfully pacing his balcony under a crescent moon (for the Shakespeare club). They’re cute in a Joan Walsh Anglund meets Harold and the Purple Crayon way that clashes with our image of what’s Goreyesque.

At the same time, they do foreshadow the Gorey we know in their careful attention to costume—his fondness for patterns (plaids, checks, stripes) is already in evidence—and in their shading, where there’s no mistaking his preference for neatly parallel lines as opposed to smudged effects or solid blacks. There’s a naive charm to Gorey’s illustrations, off-set by a self-assurance that’s remarkable in a twelve-year-old. “His things all had a common feel about them,” MacKenzie recalls, “and the instructor who was in charge”—Saunders—“said, ‘Well, [his drawings are] going to be the theme of the yearbook this year,’ and they were, and they were wonderful.”

No one seems to know exactly when Helen and Ed Gorey divorced, though just about everyone agrees it happened in 1937. Betty Caldwell, then Betty Burns, a friend Ted had made at the Linden Crest apartments, recalls the “sad day” when she had to tell him, “‘Ted, I can’t see you anymore. We’re going on a vacation; we’re going to be gone for two weeks.’ And he said, ‘Betty, it’s worse than that. My mother’s divorcing my father. We’re moving to Florida.’” On October 7, 1937, having graduated from eighth grade that June, Ted left for Florida with his mother.

Then and ever after, Gorey was silent on the subject of his parents’ divorce. Beyond a passing remark that he saw more of his parents after the divorce than before, he took the Fifth on the whole business, especially on any psychological fallout he experienced as a kid. “I don’t think I had even noticed they parted,” he claimed, preposterously, in a 1991 interview. 41In four years’ worth of diary entries, he doesn’t so much as mention his father, perhaps because they weren’t in touch, possibly because they’d never been that close, or maybe because Ed Gorey’s departure was clouded by scandal.

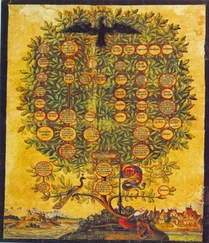

Corinna Mura in Casablanca (1942). (Warner Bros./Photofest, Inc.)

When he left Helen, sometime after June ’37, it was for another woman: Corinna Mura, a guitar-strumming singer of Spanish-flavored torch songs. She was thirty-five; Ed was thirty-nine. It seems likely they met at the Blackstone: Mura played the nightclub circuit when she was in town. In addition to her career as a nightclub chanteuse, she was an occasional movie actress. There she is, about a half hour into Casablanca : the raven-haired singer in Rick’s Café, strolling from table to table, troubadour-style, as she gives “Tango Delle Rose” her throbbing, emotion-choked all. And there she is again, a coloratura soprano amid the citoyens in the rousing scene where everyone belts out “La Marseillaise.”

On screen and on recordings such as “Carlotta” (from the original cast album of the 1944 Broadway musical Mexican Hayride ), Mura’s persona was that of a glamorous Latina—a “Spanish songstress,” in the showbiz patter of the day, at a time when “Spanish” was a blanket term for anyone we’d now call Latinx. 42

Truth to tell, Mura was born Corynne Constance Wall in Brown-wood, Texas, to David and Lillian Wall (née Jones). (Mura is what muro , Spanish for “wall,” would be, presumably, if the noun were feminine.) Her Latina persona satisfied white America’s racial fantasy of a colorful yet unthreatening otherness—“a dignified American girl” who “has the gay manner of a Latin” (as a newspaper profile put it), “cultured” enough to sing opera yet still “Mex” enough to take audiences on a journey down Mexico way. 43That said, her passion for the musical traditions and cultures of Latin America was sincere. She toured South America, where “they absolutely loved her,” according to her daughter Yvonne “Kiki” Reynolds—testimony not only to her virtuosity but to her genuine rapport with her audiences as well, since she didn’t speak a word of Spanish. (She learned her Spanish-language songs phonetically.)

On July 2, 1937, Ed Gorey was in Austin, Texas, “getting married— quietly,” he told a friend in a letter. 44By October of that year, Ted and his mother were on their way to Florida. He plotted their road trip in green crayon on the map in his travel diary. As always, he confides next to nothing to his diary, despite being uprooted, yet again, from his home and friends and despite the emotional upheaval of his parents’ divorce and his grandfather’s death. (Benjamin St. John Garvey had died the day after Ted’s birthday in 1936, shortly after speaking to his grandson on the phone.)

Arriving in Miami in November of ’37, Ted and his mother moved in with Helen’s sister Ruth—then Ruth Garvey Reark—and her children, Joyce and John (called Jack). The Rearks were living in the house Gorey’s grandmother Mary Ellis Blocksom Garvey had bought after she and Benjamin divorced. The Goreys lived in the one-bedroom, one-bathroom “independent suite,” which had a screened porch of its own. 45(It’s worth noting that, for a boy on the cusp of puberty, sharing a bedroom with his mother may have been more than a little awkward.)

On first impression, Ted struck his Reark cousins as a cosseted creature—Little Lord Fauntleroy, if he’d been “raised in a high-rise in Chicago” and “doted on by females” is how Joyce puts it. “We picked on him some,” she allows, recalling that her aunt Helen was “rather appalled at my brother and me. My mother always thought [Ted’s mother] was overprotective…. Prue and Helen just doted on Ted. She didn’t think it was good—too much feminine influence. He needed to get away from Mama, maybe.” Joyce vividly remembers Aunt Helen solemnly instructing her niece and nephew that her little wonder’s IQ was 165. “I remember being a little resentful when we were told what his IQ was…. My first reaction was, ‘Well, I don’t think he’s that special!’”

Читать дальше