While such figures underline that gardens only make up a relatively small part of the UK land area, they are the habitat within which many of us engage with birds and other forms of wildlife. This gives them special importance, not least because gardens provide the best opportunities to empower UK citizens with the conservation and research understanding needed to support sustainable planning, lifestyle and land management decisions. Birds are of particular importance in this context because they are one of the most visible, accessible and appreciated components of the wider natural world. If we can understand how they use gardens, and how this use is perceived by the people who have access to those gardens, then we can begin to provide the evidence and messaging needed to support public engagement with the natural world more widely.

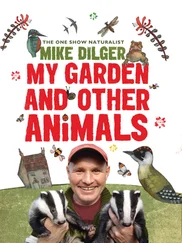

FIG 1. Private gardens vary considerably in their size, composition and use, presenting a series of different opportunities for birds. (Mike Toms)

We also need to recognise that gardens come in many different forms; at the simplest level they have tended to be split into those that are urban, suburban or rural in nature, but there is substantial variation within these broad categories. Many gardens fall within urbanised landscapes, so we also need to understand the relationships that exist between gardens and their surroundings. We know, for example, that city-centre gardens are just one form of urban green space and that birds, being mobile, will move between a city’s many different patches of such space. But how important is the spatial arrangement of these different patches or the temporal pattern of feeding resources available within them? Many of the same questions can be asked of those birds using rural gardens, perhaps bordered by arable farmland or woodland plantations. This underlines that gardens should not be viewed in isolation but rather as a part of a wider landscape over which birds may range. In some cases these ranging movements may take birds not just beyond the boundaries of the gardens and often urbanised landscapes within which they sit, but also beyond the borders of countries or even continents.

FIG 2. The Robin is perhaps the most familiar of our ‘garden birds’ but in reality it is a species of woodland edge habitats. (John Harding)

It is for this reason that this book on garden birds starts by looking at the nature of the garden habitat and the garden’s place within a wider landscape context. Inevitably, this will require us to look at urban ecology and the processes that shape the urban environment, and to look into a future where the ongoing process of urbanisation sees an ever-growing number of us living within towns and cities. We will also use this chapter as an opportunity to ask ‘what is a garden bird?’ and to examine the nature of garden bird communities. Are they, for example, just those species that happen to be generally common and widespread across the wider landscape, or is there something special about garden bird species and the communities that they form.

THE URBAN ENVIRONMENT

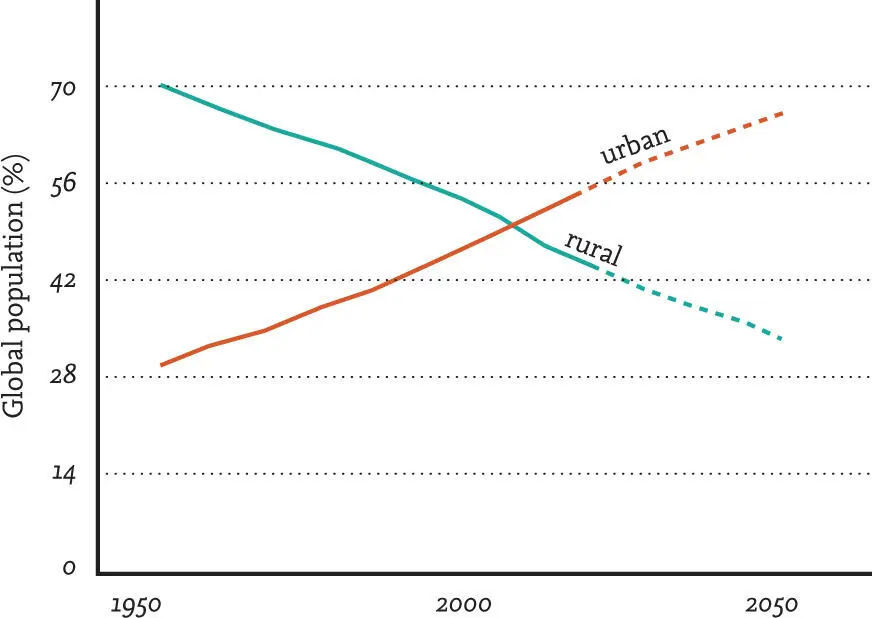

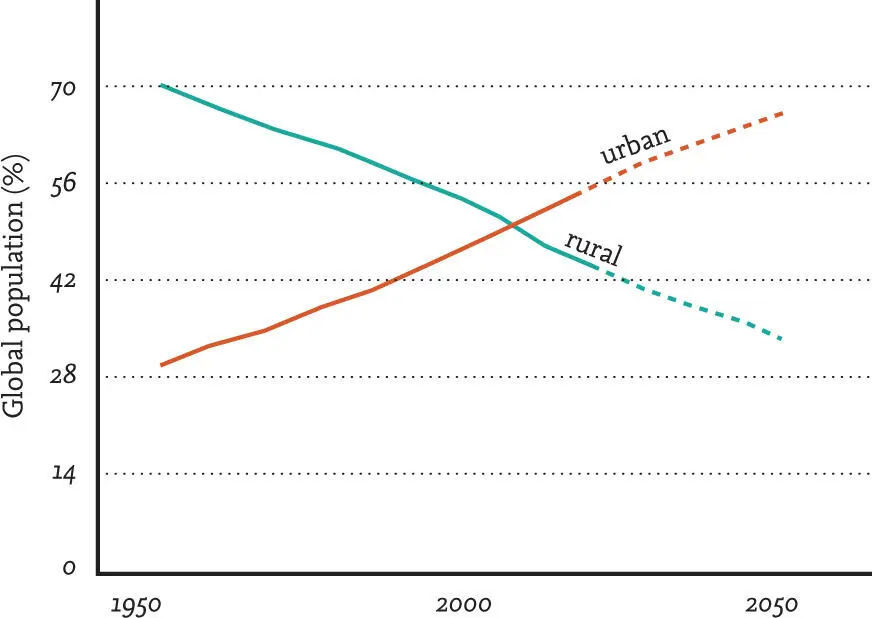

One of the most shocking statistics relating to the human population is that showing the proportion of the global population now living within urbanised landscapes (see Figure 3

); this figure, which passed 50 per cent in 2008, is projected to reach 66 per cent by 2050 (United Nations, 2014). This increase brings with it an associated increase in the amount of land under urban cover. Urbanisation is an ongoing process and considered to be one of the greatest threats facing species and their ecosystems. It is of particular concern because some of the most intensive urban development is projected to occur within key global biodiversity hotspots (Elmqvist et al., 2013). The growth in the numbers of households globally, and within biodiversity hotspot regions in particular, has been more rapid than aggregated human population growth, reflecting that average household size continues to fall. This is relevant because the reduction in average household size is thought to have added 233 million additional households to biodiversity hotspot countries alone between 2000 and 2015 (Liu et al., 2003). It seems all the more important than ever to understand the implications of urbanisation for biodiversity; to some extent this urgency has been recognised by the research community, with increasing numbers of studies helping to unravel how birds and other forms of wildlife make use of the urban environment and revealing what urban expansion means for their wider populations. Urbanisation also has implications for the ways in which the human population interacts with the wider natural world, of which it is a part, so we also need to learn about these relationships and what they mean for both birds and people; this is something that we will explore in Chapter 6

.

FIG 3. The proportion of the human population living within urbanised landscapes passed 50% in 2008 and is predicted to reach 66% by 2050. Redrawn from United Nations data.

The process of urbanisation involves the conversion of natural or semi-natural landscapes – the latter including farmed land – into ones that are characterised by high densities of artificial structures and impervious surfaces. Urbanised landscapes contain fragmented and highly disturbed habitats, are occupied by high densities of people and show an elevated availability of certain resources. Associated with the process of urbanisation is the modification of ecological processes, particularly those linked with nutrient cycling and water flow. The density of bird species within such landscapes is best explained by anthropogenic features and is often negatively associated with the amount of urban cover. This underlines the importance of urban green space, especially gardens and (for some species) urban parks and woodland. Although many bird species decline in abundance once an area has become urbanised, some are able to take advantage of the new opportunities that have been created. Because different species respond to urbanisation in different ways, we typically see a dramatic shift in the structure of avian communities living within urban landscapes and the habitats, like gardens and urban parks, found within them.

Alongside the structural changes seen, which may alter nesting opportunities or the availability of food resources, urbanisation also results in increased levels of disturbance, noise, night-time light and pollution, all of which may impact birds and other wildlife. While some of these impacts may be generally negative across species, there may be instances where such effects are not felt equally. Noise pollution can impact on some species more than others, for example, perhaps because of the frequencies at which such noise tends to occur; bird species whose songs are pitched towards lower frequencies may be affected more than those whose high-pitched songs can still be heard above the background noise. Other species may show a behavioural response, perhaps moving the time at which they sing or even altering the characteristics of the song itself. It has been found, for example, that Robin Erithacus rubecula populations breeding in noisy parts of urban Sheffield sing at night, with the levels of daytime noise experienced by these individuals a better predictor of their nocturnal singing behaviour than levels of night-time light pollution, the latter previously considered to have been the driver for nocturnal song in this species (Fuller et al., 2007a).

Читать дальше