PART ONE

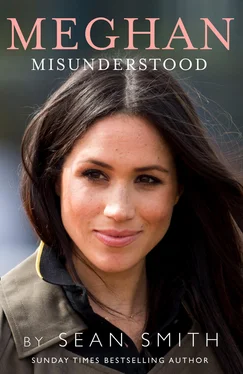

The eyes of the entire world were on Meghan Markle as she walked serenely and gracefully down the aisle of St George’s Chapel in Windsor. They have remained on her ever since.

Her wedding to Prince Harry was an occasion of great joy, representing happiness at last for the Queen’s grandson, who had captured the hearts of the nation when he disconsolately but bravely followed his mother Diana’s coffin on that eternally sad day twenty years earlier. Now he was marrying a breathtakingly beautiful woman in a story that the screenwriters of Hollywood, where Meghan had made her name, could scarcely have imagined.

At least her mother Doria was there, the only member of her family to take a place at the ceremony. She had sat beside her daughter in the Rolls-Royce as she set out on the nine-mile drive that would take her from the luxurious Cliveden House Hotel to the steps of the chapel. They were two strong women strangely unsupported in a foreign land on this grandest of May days. As always, they had each other, sharing an unshakeable bond.

A crowd estimated to be in excess of 100,000 had poured into the Berkshire town to celebrate the day with flags, bunting, laughter and cheers. Doria could have been forgiven for punching the air with exuberant joy as if her beloved daughter had just won an Olympic gold medal.

Instead of drawing attention to herself, though, Doria sat quietly in a pew across from the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh. Her eyes glistened with pride and excitement but she stayed composed, watching a woman of colour, her ‘Flower’ as she still called her, hammer loudly on the door of stuffy tradition and protocol.

There is nothing traditionally royal about Doria Loyce Ragland, memorably described by her daughter as a free spirit with dreadlocks and a nose ring. Her yoga class back in Los Angeles would scarcely have recognised the demure, stylish lady in a pale green Oscar de la Renta dress and coat. Her long hair was styled and partly hidden beneath a matching hat.

What a journey it has been for a family that historians and genealogists have eagerly traced back to the shameful days of slavery in America’s Deep South, where the persecution of the black population did not stop with the Emancipation Proclamation of 1865 that officially freed all slaves. Meghan herself has admitted that trying to unravel her family tree is a bewildering task but she is intensely proud of her biracial heritage, describing herself as a ‘strong, confident, mixed-race woman’.

Her maternal ancestors continued to face poverty and persecution for generation after generation, battling against the oppression of the Jim Crow laws, the legislation that enforced racial segregation in the southern states until 1965, two years after Dr Martin Luther King Jr’s iconic ‘I Have a Dream’ speech at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington. Then, he implored, ‘My four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the colour of their skin but by the content of their character.’

The first known records of Doria’s family show that they were slaves working on the plantations of Georgia around the town of Jonesboro, the setting for the epic novel Gone with the Wind and the famous film of that name. Fittingly, perhaps, Hattie McDaniel won Best Supporting Actress at the 1940 Academy Awards for her role as the maid ‘Mammy’, the first black winner of an Oscar.

While that was a win to be celebrated, the ceremony itself was, in retrospect, an appalling indictment of racism and segregation at the time. Hattie would not normally have been let into the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles where the ceremony was held, in its Coconut Grove nightclub; it had a whites-only policy. The film’s famous producer, David O. Selznick, called in a favour to ensure that they let the great actress in, but, even then, she had to sit at a small segregated table at the back and well out of sight.

The role of Mammy represented a dreadful white stereotype of black servants, but Hattie’s emotional acceptance speech would have inspired both Doria and Meghan. Herself the daughter of two black slaves, she said, ‘I shall always hold it as a beacon for anything that I may be able to do in the future. I sincerely hope I shall always be a credit to my race and to the motion picture industry.’

The sad reality was that by the time she died, in 1952, she had played a maid seventy-four times. Big roles did not come her way after her Oscar win: ‘It was as if I had done something wrong.’ Her dying wish was to be buried in the Hollywood Cemetery alongside the great stars of the golden age, but that was also denied by a ‘no-blacks’ policy. It would be a further seven years before racial discrimination was outlawed in California. The controversy over recognition for black actors continued into Meghan’s lifetime.

Discrimination was rife in Tennessee when Doria’s ancestors moved further north and settled in Chattanooga, a deeply racist town little deserving its place in musical history as the title of the jaunty Glenn Miller classic, ‘Chattanooga Choo Choo’. As recently as 1980, five black women were murdered there by members of the Ku Klux Klan in a drive-by shooting.

Meghan’s ancestors did not face such life-ending hatred but they still had to battle for a better life for themselves and their families. Meghan’s great-aunt Dora, for instance, was the first Ragland to go to college and became a teacher. Dora’s elder sister Lillie ran a successful real-estate business in Los Angeles and was listed in the African–American Who’s Who . She was married to Happy Evans, a famous black baseball player in the 1930s, a time when that sport was still segregated and there were separate ‘negro’ leagues.

Doria’s grandmother, Netty Arnold, worked as a lift operator at the upmarket apartment block called the Hotel St Regis in Cleveland, Ohio, where she met and subsequently married James Arnold, a bellhop. They were both black, working in a place where only whites were allowed to live.

In Cleveland, one of their daughters, Jeanette, married twice. First to a local man, Joseph Johnson, a professional roller-skater, then, following her divorce, to Alvin Ragland, who would become Meghan’s much-loved grandfather. The surname Ragland is actually one that his family took from their slave owner following emancipation.

Growing up, Meghan Markle was constantly fascinated by her family history, trying in vain to untangle its web and confessing that she was in ‘awe of her past’. Her principle problem in trying to cast light on the ‘blurred lines’, as she called them, was that black slaves were not properly documented until they officially registered. In 1870, a sharecropper called Stephen Ragland, Alvin’s great-grandfather, had become the first black Ragland.

Meghan gave a different account of that important landmark in her family history when she spoke to Elle magazine in 2015 – before she met Prince Harry: ‘Perhaps the closest thing connecting me to my ever-complex family tree, my longing to know where I came from, and the commonality that links me to my bloodline, is the choice that my great-great-great-grandfather made to start anew. He chose the last name Wisdom.’ He may well have done so informally but genealogists poring over Meghan’s ancestry have failed to find a thread linking the last name Wisdom to her family tree. Often family histories become confused by the telling and the retelling.

The Ragland family’s life changed forever when they made the 2,300-mile trek from Cleveland to Los Angeles soon after Doria was born in September 1956. There were five of them in a borrowed car: Alvin, Jeanette, her two children from her first marriage – Joseph Jr and Saundra – and baby Doria. While it wasn’t exactly an epic story matching the trip west of the Joad family in Steinbeck’s magnificent novel of the Great Depression, The Grapes of Wrath , the trip did become the subject of countless stories told to Meghan as a little girl.

Читать дальше