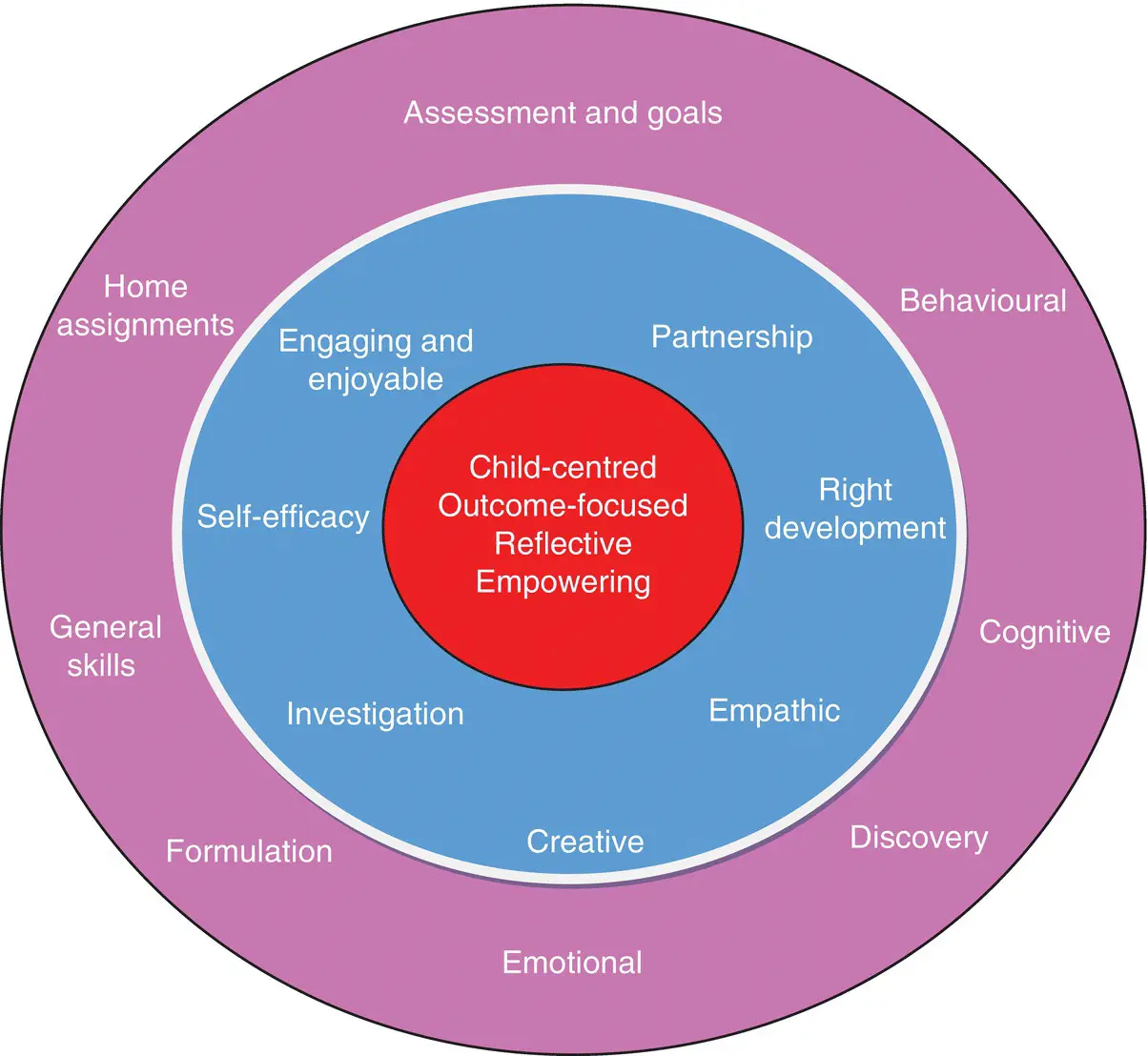

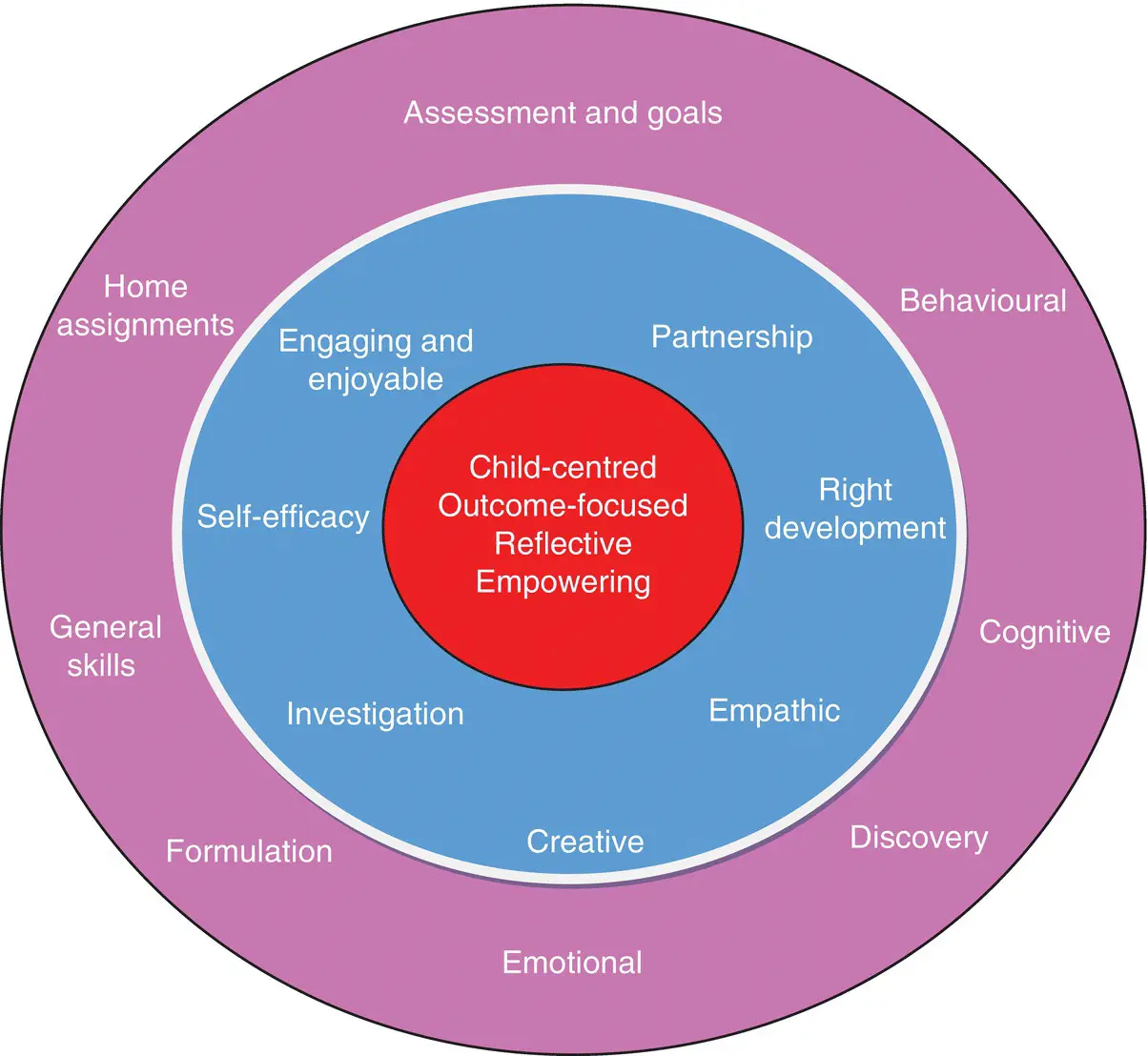

In addition to the process and core methods of undertaking CBT with children, adolescents, and young people, it is helpful to remain aware of the underlying philosophy.

This is the COREphilosophy which is

C: Child‐centred

O: Outcome‐focused

R: Reflective

E: Empowering

Figure 1.1provides a visual summary of the core philosophy, therapeutic process, and methods that embrace CBT with children, adolescents, and young people.

Figure 1.1 Core philosophy, therapeutic process, and methods of undertaking CBT with children, adolescents, and young adults.

The CORE philosophy clearly places the young person at the very centre of the intervention. Children and young people are a vulnerable group and for this reason it is important to ensure that they are safe, that potential risks are minimised, and that they are appropriately protected from potential harm. There is a need to remain mindful of potential physical, emotional, or sexual harm or exploitation from adults or peers either in person or via the Internet and to take appropriate action to safeguard the young person.

The child‐centred philosophy also ensures that the intervention remains focused on the young person and their problems. Maintaining this focus is important, particularly if parents/carers have their own problems or needs which may dominate clinical sessions and overshadow those of the young person. Parent problems may need to be directly addressed, particularly if they are significantly impacting on the young person’s problems or progress. This needs to be discussed with the parent/carer, whose problems and needs should be acknowledged, and, where appropriate, signposted or referred for direct help in their own right.

Parents/carers or other adults may have their own views about what needs to change, and this may not necessarily be shared by the young person. These views are important, and they need to be heard and acknowledged. However, adult goals may be held and ‘parked’ and returned to at a later stage. The initial focus, wherever possible, should remain on directly engaging the young person and on identifying and working towards their goals. However, the young person’s goals need to be positive and helpful and should not compromise their health or safety in any way. For example, a young person with an eating disorder may choose a goal to maintain (rather than increase) a medically concerning body weight. This would be an inappropriate goal which would compromise the young person’s physical health. This needs to be openly discussed, the reasons why this cannot be supported clarified, and alternative goals identified.

In terms of process, a key objective of the child‐centred approach is the active involvement of the young person in therapy sessions. To maximise engagement, it is important that the young person is provided with plenty of opportunities to contribute during sessions, thereby signalling that their contributions are welcomed, heard, and valued. Clinical sessions therefore need to be conducted in ways that are sensitive to the young person’s level of development and which are consistent with their cognitive, social, and emotional maturity. This will be discussed in more detail when considering the competencies required for partnership working and for pitching the intervention at the right developmental level.

In summary, the child‐centred focus ensures that the young person is safe, that their problems are the primary focus, and that the intervention is carefully attuned to their developmental level to maximise understanding, engagement, and participation.

The CORE philosophy promotes a hopeful, future‐orientated approach with a clear emphasis on outcomes, goals, and objective measurement. From the first session, the young person is encouraged to think about the future, their goals, and how things would be different if they no longer had their problems.

Typically, young people do not refer themselves for help and may not necessarily share the concerns and goals of those who referred them. This is often exemplified with school non‐attendance, where the objective of the parent and school in securing the young person’s school attendance may not be the main priority of, or indeed a goal shared by, the young person.

Young people may also be unable to think about how things could be different or identify any goals. This is a common problem with young people who become very familiar with their current situation and are unable to think about how this could change. Similarly, previous experience with adults may lead young people to assume a passive role in which they expect others to identify their problems and to tell them how they need to change, without necessarily having any ownership of either the problem or the change process.

Helpful techniques for eliciting goals are discussed in Chapter 3(Assessment and goals). For example, the miracle question offers a future‐orientated way of helping the young person to consider what their life may be like if all their problems miraculously disappeared overnight. This visualisation of a problem‐free future offers the potential to identify what might need to change to achieve this. In many cases, desired outcomes may appear daunting or feel too large or unachievable, and this can be demotivating. In order to maintain motivation, outcomes can be broken down into a series of smaller, more manageable, goals. The successful achievement of each goal takes the young person closer towards their overall objective. Goals should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and timely (SMART), thereby clearly and positively identifying what the young person hopes to achieve. The identification of clear goals ensures that the intervention remains focused and that the young person and clinician are explicitly working towards agreed objectives.

In order to maintain momentum, progress should be regularly assessed using rating scales and routine outcome measures. These provide a way of quantifying change and of capturing small, but important, changes that highlight progress. Similarly, the absence of change should prompt a curious discussion with the young person where this is acknowledged, possible reasons or barriers explored, and a plan agreed.

In summary, this future‐orientated approach focusing on outcomes is positive and empowering and from the outset builds a sense of hopefulness and a focus on change. The use of goals and routine outcome measures helps to clarify and quantify achievements, and ensures that the intervention remains focused and the young person motivated.

CBT is a reflective process in which the young person is encouraged through an open and curious approach to discover insights into their problems and difficulties and to find potential solutions and strategies that are helpful.

The CBT framework provides a simple model for bringing together different aspects of the young person’s experience that may feel random or unconnected. By encouraging the young person to attend to their thoughts, feelings, and behaviours, they are helped to understand the basic premise of the CBT model, that is, that they are connected and interlinked. Typically, this culminates in the development of a problem formulation where the young person discovers that the way they think is associated with how they feel and what they do. This understanding is empowering and can help to develop self‐efficacy as the young person and their parents are encouraged to use this understanding to consider how the current unhelpful cycle could change.

Читать дальше