This US-led retreat from peace operations had a massive impact on the UN’s response to the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, not least through the US insistence that any UN mission deployed to Rwanda be small and cheap and its repeated argument in favour of terminating the hapless UNAMIR force once the genocide was under way. In what can only be described as a ‘grave accident of timing’ (Melvern 2000: 79), the question of what sort of peace operation was required to oversee the implementation of the recently concluded Arusha Accords for Rwanda came up in the Security Council only a week after the eighteen Americans were killed in Mogadishu. Not surprisingly, the US was disinclined to despatch any new mission to Africa, but it was persuaded by European and African governments to consent to a peace operation on the condition that the force be given a narrow monitoring role and costs be kept as low as possible (Melvern 1997: 335).

The US was not alone in its scepticism towards peace operations. Following the murder of ten of its peacekeepers by extremist militias at the start of the 1994 Rwandan genocide, Belgium reversed its earlier strong support for UNAMIR and withdrew the remainder of its contingent on the grounds that there was no peace to keep and consequently little point placing its soldiers in harm’s way. Echoing US sentiment in Somalia, the Belgian government argued that continued participation in the UN mission was ‘pointless within the terms of the present mandate’ and exposed its soldiers to ‘unacceptable risks’ (Wheeler 2000: 219). The large but generally unhelpful Bangladeshi contingent quickly followed suit. In response, Major-General Roméo Dallaire recommended the reinforcement of his mission in order to avert a humanitarian catastrophe. The Security Council, however, decided instead formally to reduce the UN’s presence in Rwanda. Downgraded to a skeleton staff and volunteers, UNAMIR was unable to prevent the genocide, protect the civilian population or punish the perpetrators. In one hundred days, approximately 1 million Tutsi and Hutu moderates were slaughtered – a rate of killing higher than that of the Nazi Holocaust.

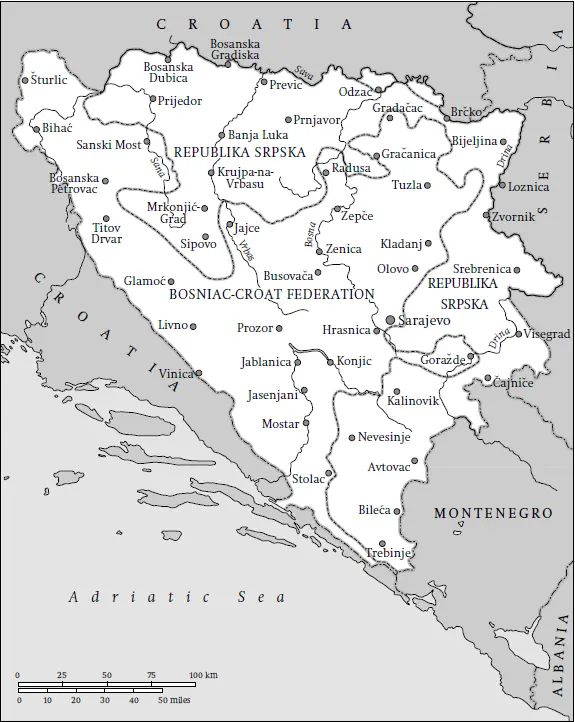

Things did not go well in Bosnia either. UNPROFOR was one of the UN’s largest and most complicated missions, not least because, as Yugoslavia dissolved, it had to straddle several newly recognized states (Koops et al. 2015: ch. 30). In February 1992, UNPROFOR peacekeepers were initially mandated to monitor a ceasefire agreement between Croatia and Serbia, which saw the creation of UN protected areas (UNPAs) in the Serb-held regions. The UNPAs were to be free from armed attack by the Croats but were also to be demilitarized by the Serbs. UNPROFOR was positioned between the armies to supervise compliance with the ceasefire agreement while political leaders sought a lasting settlement. Within six months, however, the UN confronted a humanitarian catastrophe in Bosnia because the Bosnian Serb strategy of ethnic cleansing created approximately 1.5 million refugees and would result in around 250,000 deaths. UNPROFOR was extended into Bosnia and tasked with assisting the delivery of humanitarian aid. The basic problem was that all the belligerents – but the Bosnian Serbs in particular – attempted to control the flow of aid around the country. Roadblocks often obstructed aid convoys, and international lorries carrying aid became prime targets for looting and destruction. However, UNPROFOR lacked both the means and the mandate to enforce aid delivery. Its mandate stipulated that peacekeepers could use force only in self-defence, and even if a commander decided to interpret this broadly – as several contingents tended to do – the UN lacked the resources to follow through on such a policy. UNPROFOR was confronted with a Faustian dilemma: bargain with the warlords and deliver some aid or refuse to bargain and deliver much less. Most UNPROFOR commanders chose the first option.

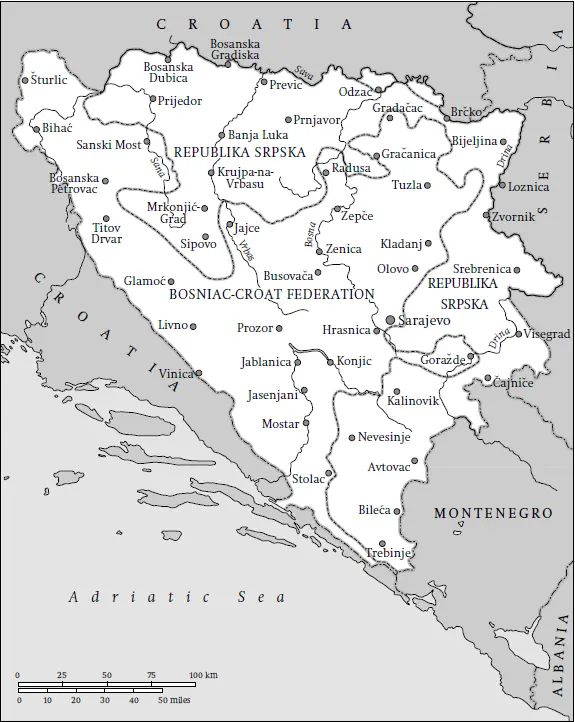

Map 4.1Bosnia and Herzegovina

As disquiet began to grow in the Western media and among peacekeepers about the UN’s failure to halt the bloodshed, questions were raised about giving UNPROFOR a mandate to use force, and the Security Council gradually expanded the mission’s mandate still further (see table 4.2). In spring 1993, UNPROFOR entered a crucial new phase when the Security Council created ‘safe areas’ in Srebrenica, Sarajevo, Goražde, Žepa, Tuzla and Bihać. The safe areas were all major towns or cities held by the Bosnian government but besieged by Bosnian Serb forces, which systematically targeted civilians with shells and sniper fire. The Security Council demanded that civilians be ‘free from armed attack’ and authorized UNPROFOR to deter such attacks. Importantly, the UN Secretary-General advised that the safe areas policy would need UNPROFOR to be reinforced by 34,000 additional troops. However, the Security Council opted for a ‘light option’ and authorized only 7,600 additional soldiers (UN 1994: 2). As a result, the Secretary-General noted, ‘the effective implementation of the safe-area concept depends on the degree of consent by the parties on the ground’ (ibid.: 3). In other words, the success of the safe areas policy depended upon the Bosnian Serbs.

Nor was UNPROFOR authorized to use force to ensure delivery of humanitarian supplies. Besieged towns such as Srebrenica were therefore dependent for supplies on (scant) Bosnian Serb goodwill. Malnutrition and disease set in. A by-product of creating so-called safe areas was that most of Bosnia became a hostile region in which UN peacekeepers had very little power. When, in summer 1995, the Bosnian Serbs decided to overrun the safe areas, UNPROFOR had neither the capability nor the mandate to prevent them from doing so. In July 1995, Bosnian Serbs seized the safe area of Srebrenica from a small contingent of Dutch peacekeepers, massacring more than 7,500 civilians as they did so (Honig and Both 1996). The Dutch commander in Srebrenica, General Herrimans, requested air strikes to repel the Serbs – as he was entitled to do under Resolution 836 (4 June 1993), which permitted UNPROFOR to ‘deter attacks against the safe areas’. But UNPROFOR’s commander, General Joulwan, and the SRSG, Yasushi Akashi, feared that substantial air strikes would take UNPROFOR across the ‘Mogadishu line’ into peace enforcement and so blocked the demand. The Bosnian Serbs seized the safe area and massacred its male inhabitants virtually unimpeded by the UN.

Table 4.2UNPROFOR’s changing mandate

| Council Resolution |

Date |

Purpose |

| 713 |

25 Sept 1991 |

Arms embargo against former Yugoslavia |

| 743 |

21 Feb 1992 |

Establishes UNPROFOR to monitor a ceasefire in the UNPAs in Croatia |

| 757 |

30 May 1992 |

Imposes sanctions on Serbia and Montenegro |

| 758 |

8 June 1992 |

Increases UNPROFOR mandate to include Bosnia and the safe delivery of humanitarian supplies |

| 764 |

13 July 1992 |

Empowers UNPROFOR to secure Sarajevo airport and its environs |

| 770 |

13 Aug 1992 |

Demands access to all refugee and prisoner of war camps |

| 776 |

14 Sept 1992 |

Enlarges UNPROFOR mandate to include the protection of convoys |

| 781 |

9 Oct 1992 |

Creates a no-fly zone over Bosnia |

| 787 |

16 Oct 1992 |

Deployment of observers to Bosnia’s borders to enforce compliance with sanctions |

| 816 |

31 Mar 1993 |

Gives members the right to enforce the no-fly zone |

| 819 |

16 April 1993 |

Designates Srebrenica a ‘safe area’ which should be ‘free from armed attack’ |

| 824 |

6 May 1993 |

Designates Sarajevo, Tuzla, Žepa, Goražde and Bihać as ‘safe areas’ and authorizes the strengthening of UNPROFOR by fifty military observers |

| 827 |

25 May 1993 |

Creates the International Criminal Tribunal for Yugoslavia (ICTY) |

| 836 |

4 June 1993 |

Gives UNPROFOR the task of ‘deterring’ attacks on the safe areas including the use of air strikes |

| 913 |

22 April 1994 |

Gives UNPROFOR responsibility for collecting and storing belligerents’ heavy weapons around Goražde |

| 998 |

16 June 1995 |

Welcomes the creation and deployment of the NATO Rapid Reaction Force |

| 1035 |

21 Dec 1995 |

Authorizes the deployment of IFOR |

The fall of Srebrenica was followed by the fall of Žepa and the near collapse of Goražde and Bihać. Srebrenica was Europe’s worst massacre since the Second World War, and it stimulated a dramatic rethink of Western policy towards Bosnia. The result was a shift to peace enforcement led by a NATO air campaign (Operation Deliberate Force) against the Bosnian Serbs and a more open strategy of providing military support to the Muslim and Croat armies on the ground. In place of the UN, Western states chose to employ force through NATO. Britain and France deployed a NATO rapid reaction force. On 30 August 1995, NATO launched Operation Deliberate Force. Supported with artillery from the Anglo-French rapid reaction force, Deliberate Force was a sustained air campaign against the Bosnian Serbs. Within four months the Bosnian war was over, the Dayton Accords were signed, and the NATO-led IFOR was deployed to assist in their implementation (see chapter 8).

Читать дальше