1 ...7 8 9 11 12 13 ...31 A first step, therefore, is to recognize that the study of peace operations can – and should – include a multiplicity of actors and levels. With regard to the actors, the most significant stakeholders might be:

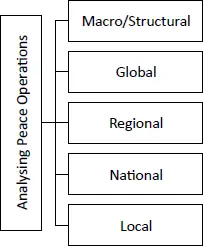

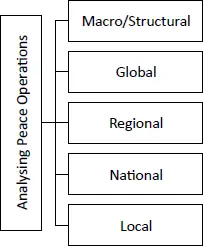

Figure 1.1 Levels of analysis for studying peace operations

members of the peace operation, including senior leadership, senior managers and representatives of its T/PCCs;

national, regional and local authorities in the host state;

international and regional organizations, among them those authorizing the mission or engaged in its theatre of operations;

external partners of the mission, multilateral and bilateral;

neighbouring states;

local and international non-governmental organizations; and

local populations in the conflict-affected areas.

In relation to the appropriate levels of analysis, we suggest at least five are relevant for studying the general phenomenon of peace operations, individual missions and particular issues (see figure 1.1). A comprehensive theory of peace operations would need to account for each as well as the relationships between them. Practical limitations of time, resources and access, however, would mean such comprehensiveness is impossible to achieve.

Macro- or structural-level theories try to explain the deep structures that shape the way peace operations are understood and practised. These include factors such as ‘global culture’, the world economy, and forces of patriarchy or racial inequality. Global-level theories are interested in understanding decision-making in international organizations such as the UN or the international financial institutions. A focus might be on how ideas about legitimacy, norms and power politics shape political decisions or the way in which organizations develop their own bureaucratic pathologies and blindspots that influence how they interpret the world and interact with other actors. Regional-level analysis would focus on the same issues, but for regional arrangements, and help explain how states in geographic or functional regions might develop shared understandings about the role of peace operations which may differ from other regions. National-level studies have focused either on individual missions or the peacekeeping policies of particular countries. Studies focused on the local level have analysed a wide range of issues, from the impact of peace operations on ‘the peacekept’ (Clapham 1998) – the local populations on the receiving end of such missions – to studies of operational and tactical details about individual missions, such as the behaviour of particular contingents and mission components, specific mandated activities, or the psychology of peacekeepers themselves.

No single level is necessarily better or more accurate than the others, nor do they stand in isolation from the other levels. The important point to recognize is that, whether self-consciously or not, analysts prioritize levels and units of analysis; they are neither natural nor predetermined. In the chapters that follow, our analysis draws insights from each of the levels and across a variety of perspectives from relevant stakeholders.

In addition to understanding the different levels of analysis, it is important to note two general points about peace operations. First, whatever objectives peace operations are mandated to achieve, they always generate a series of unintended consequences. Unintended consequences refer to any developments directly generated by the operation that were not intended by those who planned it (Aoi et al. 2007). They are inevitable when large peace operations deploy to the complex social systems that characterize war-torn societies. Some unintended consequences can be foreseen and anticipated; others might be impossible to predict. Their effects can be politically positive, negative or neutral. Negative consequences have often captured the media headlines – such as peacekeepers engaging in SEA (see chapter 17) or introducing cholera to Haiti (as the Nepalese contingent did in late 2010). Some analysts also claimed peacekeepers were ‘among the primary mechanisms of spreading the disease [HIV/AIDS] at a mass level to new areas’ (Singer 2002: 152; see also Elbe 2003: 39–44). Although subsequent evidence did not support this conclusion, some reputational damage was done. More positive but apparently less newsworthy activities conducted outside of the formal mandate include peacekeepers donating blood to local hospitals, sharing food and medical supplies with locals, or helping to build bridges, roads, schools and children’s play areas. Negative unintended consequences can be damaging in several respects: they can cause suffering for individuals and communities where peace operations are deployed; they can reduce the ability of the peacekeepers to achieve their intended objectives; they can undermine the idea that peace operations are positive phenomena that should be encouraged and supported; and they can erode the legitimacy of the organizations that authorize and supposedly supervise them (Aoi et al. 2007: 8).

Second, peace operations generate a range of ethical and moral issues, challenges and dilemmas. These can be crudely divided into general issues and the range of personal ethical choices that confront individual peacekeepers. General ethical questions might be whether it is ethically acceptable that most peacekeepers come from some of the world’s poorest countries or that foreigners should govern locals during transitional administrations. Other moral dilemmas include the ethical basis for privatizing aspects of peace operations or weighing the ethical consequences involved if some peace operations provide support for authoritarian regimes. At a personal level, all UN peacekeepers are required to abide by the organization’s core values of integrity, professionalism and respect for diversity. What should happen to those who do not? In addition, peacekeepers will face lots of ethical choices during their deployments. For example, when should peacekeepers decide to intervene in local disputes? When and how should peacekeepers use force? How much risk should peacekeepers be willing to assume in order to protect local civilians? And why do some peacekeepers choose to participate in immoral, illicit or criminal activities such as sexual exploitation and abuse or trading commodities on the black or grey markets? In sum, when studying peace operations it is important to remember that they are sites of important and complex ethical issues.

This is made explicit by some of the major theories about peace operations. In the remainder of this section, we briefly sketch five of the most prominent theoretical frameworks for thinking about peace operations and their roles in global politics, namely, liberalism, culture, cosmopolitanism, imperialism and critical theory.

Without doubt this has been the most influential theory in relation to peace operations. It is not hyperbole to say that both the theory and the practice of the vast majority of peace operations have been informed by a commitment to the liberal peace (see Paris 1997, 2002, 2004). At the interstate level, liberal peace is based on the observation that democratic states do not wage war on other states they regard as being democratic. This is not to argue that democracies do not wage war at all or that they are less warlike in their relations with non-democracies, only that democracies tend not to fight each other. In addition, liberal democracies are said to be the type of states least likely to descend into civil war or anarchy.

Exponents of this theory generally present two reasons to explain why that might be. First, through their legislatures and judiciaries, democratic systems impose powerful institutional constraints on decision-makers, inhibiting their opportunities for waging war rashly (Owen 1994: 90). These inhibitions are further strengthened by the plethora of international institutions (such as the UN) to which liberal democratic states are tied. Democracy prevents civil war primarily because it guarantees basic human and minority rights and offers non-violent avenues for the resolution of political disputes. The second explanation of liberal peace is normative and holds that democratic states do not fight each other because they recognize one another’s inherent legitimacy (Owen 1994) and have shared interests in the protection of international trade which are ill-served by war (Hegre 2000). Within states, the legitimacy associated with democracy makes it very difficult to mobilize arms against the prevailing order, reducing the likelihood of civil wars. In arguing that peace operations are informed by liberal peace theory, we mean that many of them have been mandated to stabilize war-torn territories by promoting and defending liberal principles of politics, economics and even society (see box 1.1).

Читать дальше