This framework is sufficiently general to encompass a number of subprocesses. For example, Sorensen (2000) and Mileti and Sorensen (1990) have described 11 communication factors associated with the eventual behavioral response, namely: electronic channel, media, siren, personal versus impersonal messages, message specificity, number of channels, frequency, message consistency, message certainty, source credibility, and source familiarity. Other factors include demographic variables (age, gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, family size, parenthood), attitudes and experiences (knowledge and attitudes about risks, fatalistic beliefs), and structural and community factors (community involvement and planning). The range of factors influencing warning systems is thus quite complex, involving a diverse message, audience, and social variables.

These factors influence the warning process at many points. For example, communication variables such as channel influence both risk identification and risk assessment. Consistency of message, specific information, frequency, and credibility are all factors associated with the persuasiveness of a message in terms of risk identification and assessment. Decisions about risk reduction, feasibility, and, ultimately, the protective response may be influenced by factors such as message specificity and message certainty.

Strengths and Weaknesses of the Hear-Confirm-Understand-Decide-Respond Model

The Hear-Confirm-Understand-Decide-Respond model is a useful and comprehensive way of framing warning messages within larger systems and more general models, and it accommodates basic principles of communication effectiveness. Its predictive value, as research has shown, is in demonstrating that basic principles of effective communication, such as consistency, repetition, understandability, and credibility, facilitate the effectiveness of warnings. As a general framework, it is very flexible and parsimonious but does not address many of the more specific processes of warnings as a form of risk communication. The framework makes limited reference to audience or contextual factors that may influence perceptions, interpretation, and action. These factors, including the level and form of the specific risk and previous experiences with risks, are important features of any risk communication process. Moreover, this model does not explicitly predict the effectiveness of warning messages in generating desired behavioral outcomes. In addition, this approach to public warnings does not reference interactions and feedback loops among the three subsystems. As with other linear models, the Hear-Confirm-Understand-Decide-Respond model may fail to capture the dynamic nature of communication processes.

Protective Action Decision Model

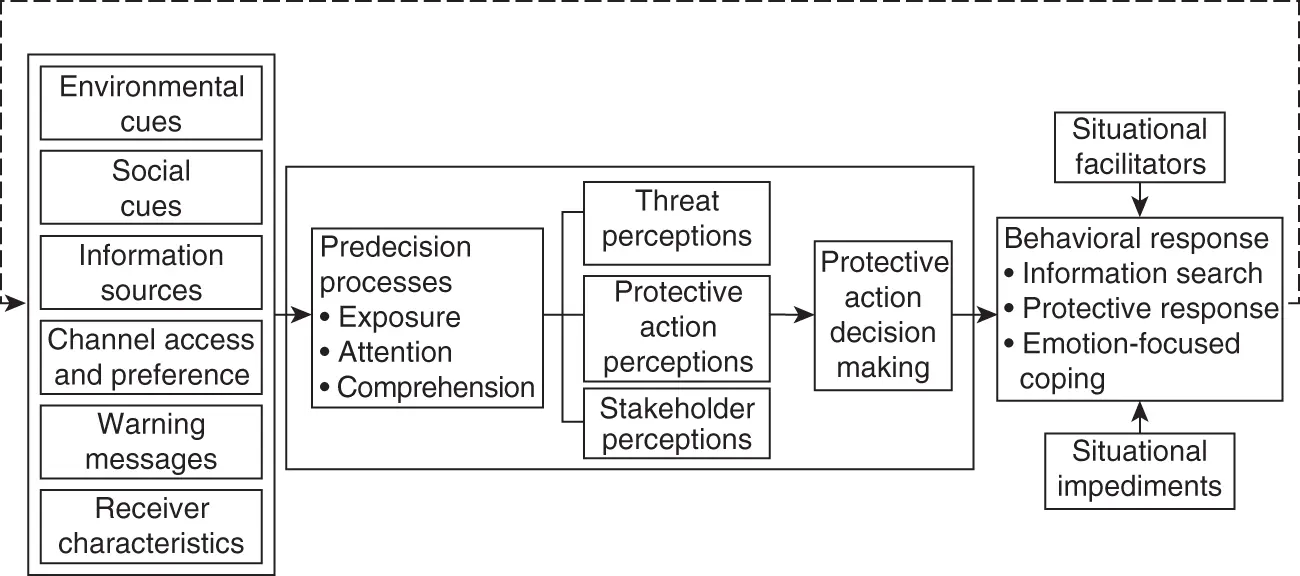

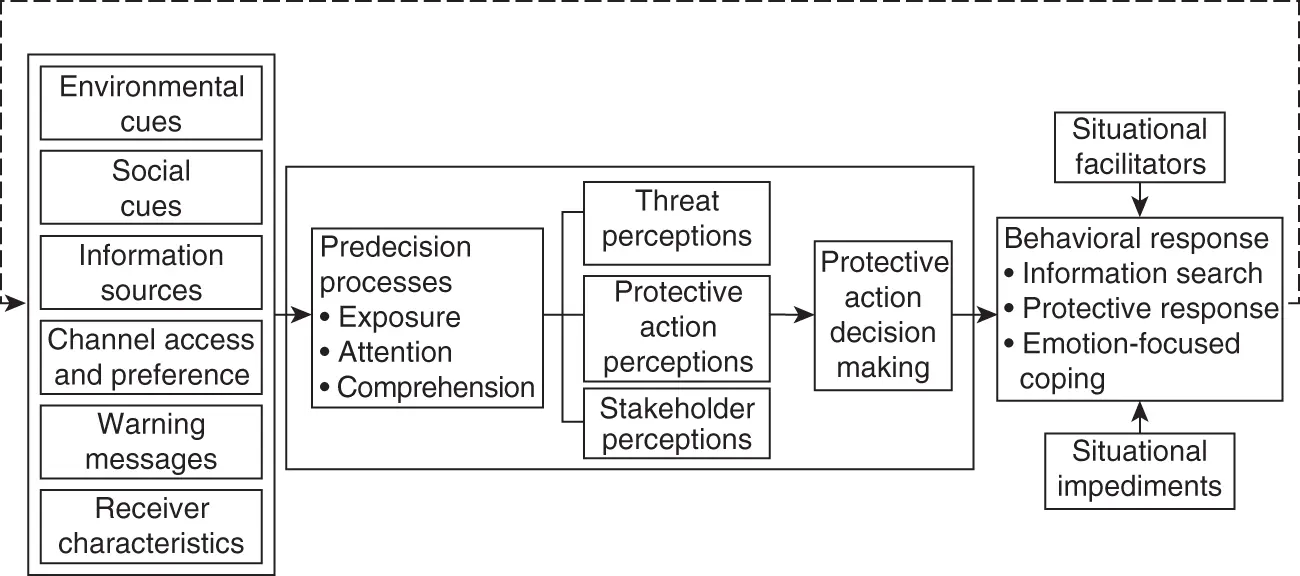

Michael Lindell and Ronald Perry have developed a robust warning message and decisional framework called the PADM (Lindell & Perry, 1992, 2004, 2011). They describe many of the same processes of warning systems as Mileti but link them more explicitly to decisional systems. The model examines the features of information and environmental and social cues necessary to inform specific protective behaviors. A significant body of research has indicated that the public’s response to a risk is a function of environmental cues; hazard information, usually coming from agencies and authorities; mass media messages; and cues and information from peers, neighbors, friends, and so on (see Lindell & Perry, 2004; Mileti & Sorensen, 1990). Message features such as credibility, consistency, and consensual validation all play a role in how warning messages are received, interpreted, and eventually acted upon. The PADM, then, is a multistage model that seeks to identify and describe the factors that influence responses to hazards and disasters and the relationships between these factors. Thus, it creates a more comprehensive view of the warning process from pre-event factors and perceptions through the decision to take some action.

Lindell and Perry (2004) ground the PADM both in classic approaches to persuasion, which emphasize the relationship between communication and influence, and in behavioral decision theory, which focuses on cognitive processes (p. 45). In addition, the PADM is grounded in work that connects cognitive processes and behaviors. They note:

This research has found that sensory cues from the physical environment (especially sights and sounds) or socially transmitted information (e.g., disaster warnings) can each elicit a perception of threat that diverts the recipient’s attention from normal activities. Depending on the perceived characteristics of the threat, those at risk will either resume normal activities, seek additional information, pursue problem-focused actions to protect people and property, or engage in emotion-focused actions to reduce their immediate psychological distress. Which way an individual chooses to respond to the threat depends on evaluations of both the threat and the available protective actions.

(Lindell & Perry, 2004, p. 46)

Their model seeks to explain this decisional process according to three general subprocesses (see Figure 3.3). First, the warning process identifies the elements of the communication processes associated with communicating the warning. These factors include source characteristics, channel access and preference, message characteristics, receiver characteristics, and other informational sources such as social cues and environmental cues. Components of the warnings system, such as width of diffusion, credibility, timing, and so on, are directly related to the ability of a target audience to receive and process threat information.

Figure 3.3Information Flow in the PADM.

Source: Lindell and Perry (2011). Reproduced with permission of Blackwell Publishing Inc.

The second component, pre-event factors and perceptions, describes the reception-processing component of the decision. These are the elements undertaken by an audience member after receiving the warning. Pre-decisional processes of reception, attention, and comprehension of warnings all occur before any further processing of the information about a risk. The model describes three forms of audience perception that influence the processing of information: threat perceptions, protective action perceptions, and stakeholder perceptions. These perceptions may be understood as filters or interpretive frames that are used in processing the warning message. The individual conducts a kind of personal risk assessment, taking into account factors such as proximity to the risk, certainty, severity of the threat, and immediacy of the hazard (Lindell & Perry, 2004, pp. 51–54).

The third subprocess involves behaviors. The outcome of the protective action decision-making process, together with situational facilitators and impediments, is to produce a behavioral response. At this point, the individual undertakes a protective action search to identify possible actions to take. These may come from previous experience and education, communication with others, or through additional information seeking (Lindell & Perry, 2004, pp. 55–56). These possible protective actions are evaluated based on efficacy, cost, safety, time requirements, and the perceived barriers to implementation.

Individuals ask eight general questions as they process warnings and face risks. These are information-seeking questions “regarding the threat, protective actions, and social stakeholders” (Lindell & Perry, 2004, p. 64) (see Table 3.2). These questions track the decisional process through eight stages. The first questions concern the nature of the risk: Is the threat real? Is action required? These are followed by questions about protective actions: What is available? How can these be accessed? How would they be implemented? The final three questions concern additional information and methods by which information can be obtained.

Читать дальше