If the regime consolidates itself, it must decide how far to go in transforming Afghanistan society. The five-year plan now being prepared is intended to introduce the first serious industrialisation in the country’s history.

The intention is for the share of industry to increase with each subsequent five-year plan. Agriculture is to be collectivised on a voluntary basis following land reform. Private enterprise, is eventually to be abolished, and the 10 per cent of the population which is nomadic is to be offered land for voluntary resettlement.

Western experts view this programme with distrust. They believe Afghanistan cannot be competitive as an industrial society and have urged diversification of agriculture with concentration on cash crops such as cotton, nuts and dried and fresh fruit.

In keeping with national pride and the regime’s “antiimperialist” bias, the Afghans have rejected this advice and although dependent on outside sources for an estimated 70 per cent of the funds for their five-year plan—most from the Eastern Bloc—they are going ahead with capital intensive projects such as exploitation of the Ainak copper deposits. This will isolate them from the world economy and tie them irrevocably to the Soviet Union.

The effective date of the decree on land reform has been postponed until next autumn—in effect, for two more harvests—and the article abolishing peasants’ debts to money lenders is, in many cases, being ignored by peasants who are paying their debts lest they be deprived of credit to get seed for next year’s planting.

There seems little doubt, however, that if the regime wants to make rapid progress in industrialisation and collectivisation it will at some point have to decide whether to use overwhelming force to achieve its ends.

There is another worldly quality to this remote, mountainous country where life seems to centre on prayer, the local tearooms, which are full of animated Afghans at the height of the working day, and the campfires of tribal nomads, which dot the side of the main highway to the capital at night. The reaction to an attempt to destroy the traditional patriarchal society by Marxist-Leninist ideology would probably throw the country into chaos.

There is however some backing in Afghanistan for forcible methods.

If the Khalqi regime emerges as militantly revolutionary, its activities could also have an international dimension. The regime could inspire increased violence in Pakistan and Iran by giving support, at the Soviet Union’s behest to the left-wing separatist movement, acting on behalf of 5 m Baluchi tribesmen.

If the Baluchis, using Afghanistan as a staging area, are successful in separating Baluchistan from Pakistan—and there are many who believe that in the medium term they will make the attempt—Afghan militancy would have helped destabilise the regional balance, allowing the Soviets, at long last, to realise the long-held aspiration of dominating Afghanistan and Baluchistan, thus achieving a warm water port—Gwadar—on the Arabian sea.

Financial Times, Wednesday, March 8, 1978

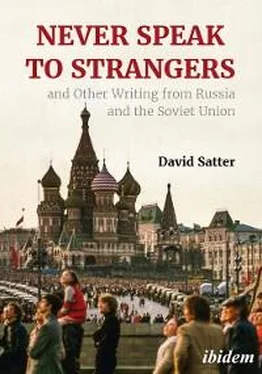

David Satter visits Murmansk, the USSR’s Arctic metropolis

Russia’s ‘Civilised North’

The low-lying Arctic sun burns through the white mist for only a few hours in midwinter as Murmansk, the world’s largest city north of the Arctic Circle, emerges from the total darkness of three months of polar nights.

Beyond the pillared stone buildings on Lenin Prospekt, the city’s main street, the railway yards and massive harbour, with its steam-shrouded cranes and ocean-going ships, testify to the accident of geography which is the city’s raison d’être .

Although 69 degrees north, Murmansk has the only ice-free port in North European Russia at the eastern end of the Gulf, Stream. The city has become, perforce, a social laboratory for testing man’s ability to thrive in arctic conditions.

Murmansk is 1,000 miles north-west of Moscow at the top of the sparsely populated Kola Peninsula. There are no nearby cities of any consequence and, with little in the way of cultural facilities, Murmansk is one of the most isolated cities of its size in the Soviet Union.

The most difficult adjustment for Murmansk’s new residents, however, is getting used to three months of total darkness between mid-October and mid-January. This is followed by a three month period in the summer when there is no darkness at all.

Under these conditions, Murmansk could have the same difficulty holding population as new cities in remote areas of Siberia. But although 5,000 to 6,000 persons leave Murmansk every year, the city’s population has grown by 8,000 a year since 1959. This is a tribute to the complex of economic, health and recreational measures designed to keep it functioning.

Murmansk is what its residents call the “civilised north” to distinguish it from cities in Siberia where conditions are primitive. There is a housing shortage in Murmansk, as elsewhere in the Soviet Union, and many live in communal flats.

But the housing stock is modern and with 400,000 inhabitants, Murmansk boasts the largest library and the only trolleybus service north of the Arctic Circle.

This winter in Murmansk has been one of the worst in memory with temperatures hovering around −30 centigrade. For the first time in 13 years, passenger ship transport to the port, a major transit point for Soviet goods shipments, actually stopped on February 14.

Despite difficulties, however, the port, which was the destination of Allied convoys during the Second World War, was soon operating again and this reliability in a country largely frozen in winter is what has made Murmansk an essential urban centre.

The impressive harbour is used extensively by the Soviet northern fishing fleet, which is serviced by Sevryba, the Soviet Union’s largest fish processing combine. Although the catch from the Barents Sea is declining after years of over-fishing, Murmansk remains one of the Soviet Union’s biggest fish centres.

The Soviet naval presence is even more important but less obvious. The northern fleet in Murmansk and the nearby submarine base of Severomorsk constitutes the greatest concentration of naval military power in the world. Western intelligence places the strength of the northern fleet at 51 surface ships and 126 submarines, of which 54 are nuclear powered.

The use by commercial and military shipping of the fiord like Kola Bay is so intensive that there is no place on the bay set aside for recreational purposes. It is this concentration of activity, carried on for months in sub-zero cold and often in conditions of total darkness, which is made possible ultimately by the social measures to maintain Murmansk in a desolate area where snow falls 10 months out of the year and trees only reach sapling size after 65 years.

The most important incentive to work in Murmansk is economic. On arrival, a worker receives a 40 per cent pay increase raised at six months’ intervals by 10 per cent, until, after four years, he is earning at least 200 per cent of what he would have earned at a job farther south.

The number of people employed in the fishing industry is expected to decrease with technological improvement and the declining catch in northern waters. Plans call for the development of light industry, including knitted ware, manufacturing and the opening of a vodka factory to save the cost of transporting bottles 900 miles up the railway line.

The goal of holding population in the far north would probably not be achieved, however, were it not also for Murmansk’s comprehensive health care system. The long Polar night and a period in February and March when the sun shines but gives off no ultra-violet rays can cause severe vitamin deficiencies. These are warded off by ultraviolet lights in factories and schools and daily vitamin doses for every Murmansk resident at “health points.”

Читать дальше