To develop this understanding and consider how this potential may be realized to ‘test the present’ (Stengers 2019), the book outlines a compositional methodology. The distinctiveness of this methodology comes from an emphasis on the vocabulary of composition, 2a term that Whitehead employs in the quotation above, but whose everyday definition is ‘the action of putting things together’. Here it refers to the processes, the activities with which the givens, goals and operators of a problem space are put together. When the term composition is used in the visual and performing arts the emphasis is on the creativity of this action of putting things together. It is used here – in a way that it is hoped will be of interest to disciplinary and interdisciplinary researchers of all kinds – to describe a methodology in which the focus is on the ways in which a problem is put together, how it is formed and transformed, inventively (Lury and Wakeford 2012). In this process of putting a problem together, of forming and transforming, the compulsion of composition does not come from either inside or outside the problem; the problem is not acted on in a space but emerges across a problem space, from with-in and out-with.

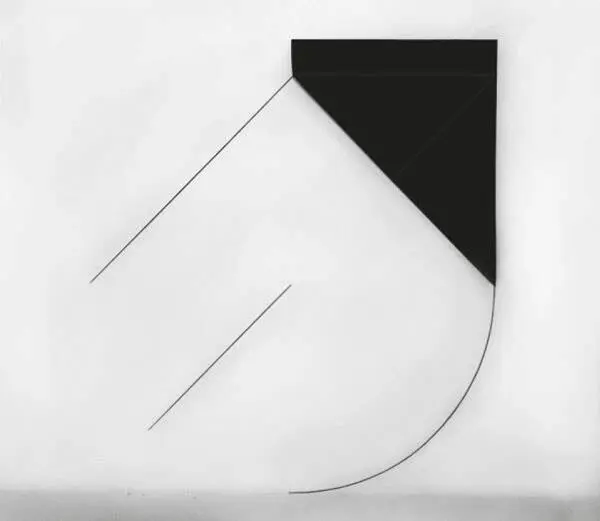

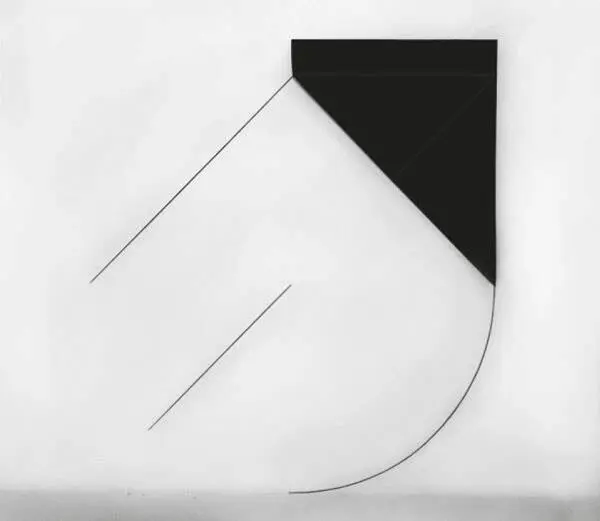

For compositional methodology, an understanding of a problem as a form of process is fundamental, where form consists in both the problem and its limits or constraints. 3To explicate this understanding of form, let me introduce a series of works by the artist Dorothea Rockburne: Drawing Which Makes Itself (1972–3). In these works, a double-sided piece of carbon paper, which I invite you to consider as analogous to a phenomenon or situation becoming a problem, is held against a wall or a floor, folded and rotated, with the edges or limits of the space it makes in these activities scored through the paper onto the wall or floor. The activities (the methods) of folding, rotating and scoring move the paper (the problem) into and through another dimension in a process of transformation. The art critic Rosalind Krauss says of these works:

The act of scoring simultaneously deposits carbon onto the wall surface and underlines the fold of the paper itself. The resultant lines or marks are read with a striking ambivalence, for they are both on the wall and yet they are retained within the carbon paper that had been flipped into a new position. … one confronts works in which the lines [that are ‘out-with’ the paper] arise from information that is ‘[with]in’ the paper. (2010: 221)

Figure 1 Installation piece: Arc

Source: Dorothea Rockburne (1973) © ARS, NY and DACS, London 2020

Acting methodically on the properties of a situation becoming a problem (trans)forms the problem. The limits of the problem are with-in and out-with it: they do not contain it, but, rather, express or encapsulate it.

The material-semiotic properties of the double-sided carbon paper mean that some acts – some methods – have expressive effects; it is a drawing that draws itself. At the same time, not only do the material-semiotic properties of the paper – the problem – have methodological potential (to be folded, to be scored, to be rotated), so too does the context in which the work is (re-)presented matter. Rockburne says the context should ‘represent’ the art. To do so requires that the context be (re)active:

I was very interested in the fact that the whole room should represent the art. I painted the walls with the brightest white paint you could find. As people walked into the room, their footprints became part of the drawing. ( https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-1010/minimalism-earthworks/v/rockburne-drawing)

Inspired by this work, the concept of a problem space put forward here is that it is a space of methodological potential that is with-in and out-with the ongoing transformation of a problem. The potential is realized in a methodology that, rather than responding only to the initial presentation of a problem, composes the problem again and again.

Compositional methodology

The activity of composing is not given in advance of a problem, but is rather ever forming and transforming across a problem space. It rarely involves just one action or operation – sensing, categorizing, conceptualizing, scaling, measuring, affecting, experiencing, varying, but involves the doing of many together. In other words, compositional methodology presumes and exploits the fact that a problem is not given but emerges with-in and out-with a myriad sequence of actions or methods that (trans)forms the problem space. Importantly, this sequencing is not the addition of one action or method after another, but a composition in the sense that the actions or methods are not discrete or independent of each other. As ‘it’ happens, a compositional methodology seeks to recognize and exploit the properties of the problem on an ongoing basis. It composes a problem by recognizing and making use of (rather than minimizing) the constantly changing limits that create a problem and a problem space together, identifying and operating the intensive or ‘live’ properties of the problem it investigates (Back and Puwar 2012).

Compositional methodology is, then, concerned with form in and as transformation, a process involving ‘the interweaving of data, form, transition, and issue’ (Whitehead 1968: 210) organized by the compulsion of composition:

It is not that which is discriminated that is most real, nor is it a completed, self-sustaining composition. But instead the compulsion of composition. (Whitehead 1968: 133)

To adapt Rockburne’s title, for compositional methodology a situation or phenomenon becomes a problem, acquires a form, trans-forms, as a ‘problem that problematizes itself’; that is, compulsive composition is the repeated folding or twisting of problems into forms of problematization. In this twisting, the problem is revealed never to be simply a problem, but also a composition of the methodological potential of a problem space to be expressed in transformation. This is to say problems and problem spaces are compulsively composed together.

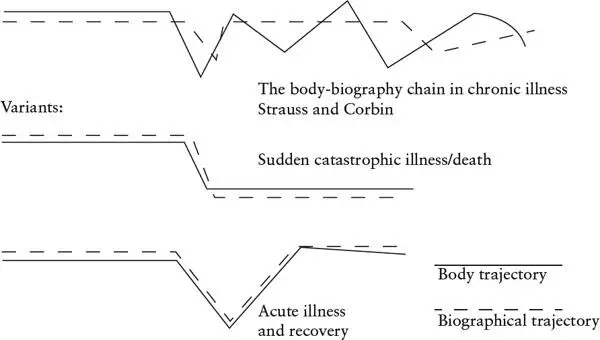

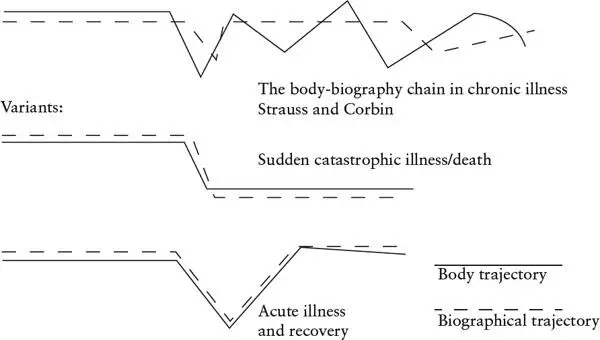

Let me give another example, taken from a discussion of the development of staging models for the diagnosis of tuberculosis by Geoff Bowker and Susan Leigh Star (2000). In a first model – a body–biography chain, the biographical trajectory of an individual and the trajectory of their illness are placed alongside each other.

Figure 2 Model I: Body–biography trajectory

Source: Geoff Bowker and Susan Leigh Star (2000)

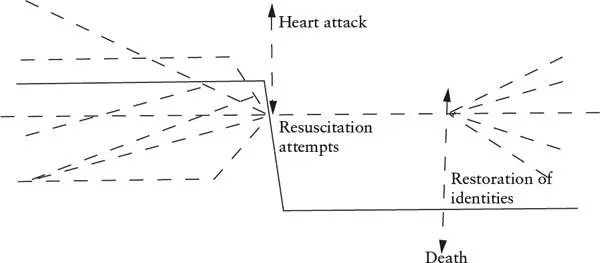

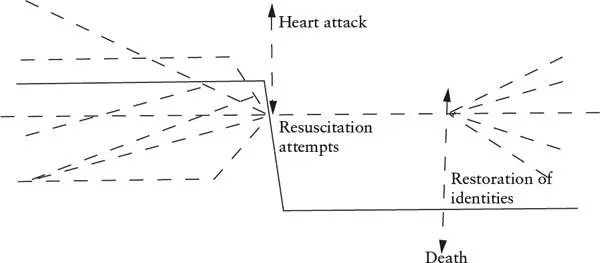

In a second model, multiple biography/identity trajectories are introduced, as a way of recognizing the multiple dimensions of an individual’s life, complicating the understanding of the course of illness in relation to the person who is ill.

Figure 3 Model II: Multiple identity trajectory

Source: Geoff Bowker and Susan Leigh Star (2000)

In both these models, the problem space is a container space. However, in a third model, the external linear time of the classification system is folded into the model: continuities, discontinuities and layers are introduced into the problem space. In the action of folding the epistemic limit of the classification system across the trajectories, the model becomes expressive; that is, the model acquires inventive methodological potential in the folding of ‘the outside’ of the problem into the ‘inside’. It is encapsulated. As Bowker and Star put it, there is a topology–typology twist: ‘The topology created by the body–biography trajectory is pulled against the idealized, standardized typology of the global classification of tuberculosis, itself a broken and moving target’ (2000: 190).

Читать дальше