It is difficult within our contracted limits to give an accurate character of Voltaire. In versatility of powers, and in variety of knowledge, he stands unrivalled: but he might have earned a better and more lasting name, had he concentrated his talents and exertions on fewer subjects, and studied them more deeply. It has been truly and wittily observed that “he half knew every thing, from the cedar of Lebanon to the hyssop on the wall; and he wrote of them all, and laughed at them all.” Of the feeling of veneration, either for God or man, he seems to have been incapable. He thought too highly of himself to look up to any thing. Capricious, passionate, and generally selfish, he was yet accessible to sudden impulses of generosity. He was an acute rather than a subtle thinker. Perhaps in the whole compass of his philosophical works there is not to be found one original opinion, or entirely new argument; but no man ever was endowed with so happy a facility for illustrating the thoughts of others, and imparting a lively clearness to the most abstruse speculations. He brought philosophy from the closet into the drawing-room. Eminently skilled to detect and satirize the faults and follies of mankind, his love of ridicule was too strong for his love of truth. He saw the ludicrous side of opinions in a moment, and often unfortunately could see nothing else. His alchymy was directed towards transmuting the imperfect metals into dross. All enthusiasm, eagerness of belief, magnifying of probabilities through the medium of excited feeling, all that makes a sect as well in its author as its followers, these things were simply foolish in his estimation. It is impossible to gather from his works any connected system of philosophy: they are full of contradictions; but the pervading principle which gives them some form of coherence is a rancorous aversion to Christianity. As a Deist believing in a God, “rémunérateur vengeur,” but proscribing all established worship, Voltaire occupies a middle position between Rousseau on the one hand, who, while he avowed scepticism as to the proofs, professed reverence for the characteristics of Revealed Religion, and Diderot on the other, with his fanatical crew of Atheists, who laughed not without reason at their Patriarch of Ferney, for imagining that he, whose life had been spent in trying to unsettle the religious opinions of mankind, could fix the point at which unbelief should stop. The dramatic poems of Voltaire retain their place among the first in their language, but his other poetical works have lost much of the reputation they once enjoyed. He paints with fidelity and vividness the broad lineaments of passion, and excels in that light, allusive style, which brings no image or sentiment into strong relief, and is therefore totally unlike the analytic and picturesque mode of delineation, to which in this country, and especially in this age, we are apt to limit the name and prerogatives of imagination. As a novelist, he has seldom been equalled in wit and profligacy. As an historian, he may be considered one of the first who authorized the modern philosophizing manner, treating history rather as a reservoir of facts for the illustration of moral science, than as a department of descriptive art. He is often inaccurate, and seldom profound, but always lively and interesting. On the whole, however the general reputation of Voltaire may rise or fall with the fluctuations of public opinion, he must continue to deserve admiration as

“The wonder of a learned age; the line

Which none could pass; the wittiest, clearest pen;

The voice most echoed by consenting men;

The soul, which answered best to all well said

By others, and which most requital made .”—Cleveland.

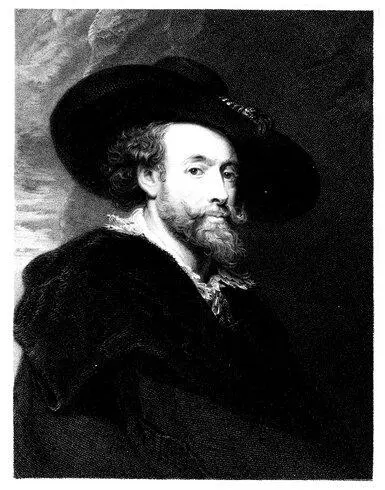

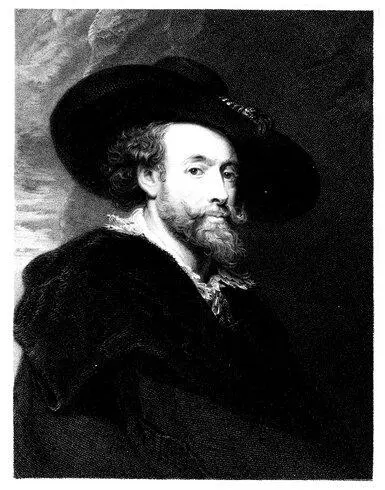

Engraved by J. Posselwhite. RUBENS. From the original Picture by himself, in His Majesty’s Collection. Under the Superintendance of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. London, Published by Charles Knight, Pall Mall East.

Table of Contents

The father of this great painter was a magistrate of Antwerp, who, during the desperate struggle of the Netherlands to shake off the dominion of Spain, retired from his own city to Cologne, to escape from the miseries of war. There, in the year 1577, Peter Paul Rubens was born. At an early age he gave indications of superior abilities, and his education was conducted with suitable care. The elder Rubens returned to Antwerp with his family, when that city passed again into the hands of Spain. It was the custom of that age to domesticate the sons of honourable families in the houses of the nobility, where they were instructed in all the accomplishments becoming a gentleman: and in conformity with it, young Rubens entered as a page into the service of the Countess of Lalain. The restraint and formality of this life ill suited his warm imagination and active mind: and on his father’s death, he obtained permission from his mother to commence his studies as a painter under Tobias Verhaecht, by whom he was taught the principles of landscape painting, and of architecture. But Rubens wished to become an historical painter, and he entered the school of Adam Van Oort, who was then eminent in that branch of art. This man possessed great talents, but they were degraded by a brutal temper and profligate habits, and Rubens soon left him in disgust. His next master was Otho Van Veen, or Venius, an artist in almost every respect the opposite of Van Oort, distinguished by scholastic acquirements as well as professional skill, of refined manners, and amiable disposition. Rubens was always accustomed to speak of him with great respect and affection, nor was it extraordinary that he should have conceived a cordial esteem for a man whose character bore so strong a resemblance to his own. From Venius, Rubens imbibed his fondness for allegory; which, though in many respects objectionable, certainly contributes to the magnificence of his style. In 1600, after having studied four years under this master, he visited Italy, bearing letters of recommendation from Albert, governor of the Netherlands, by whom he had already been employed, to Vincenzio Gonzaga, duke of Mantua. He was received by that prince with marked distinction, and appointed one of the gentlemen of his chamber. He remained at Mantua two years, during which time he executed several original pictures, and devoted himself attentively to the study of the works of Giulio Romano.

In passing through Venice, Rubens had been deeply impressed with the great works of art which he saw there. He had determined to revisit that city on the first opportunity, and at length obtained permission from his patron to do so. In the Venetian school his genius found its proper aliment; but it is perhaps to Paul Veronese that he is principally indebted. He looked at Titian, no doubt, with unqualified admiration; but Titian has on all occasions, a dignity and sedateness not congenial to the gay temperament of Rubens. In Paul Veronese he found all the elements of his subsequent style; gaiety, magnificence, fancy disdainful of restraint, brilliant colouring, and that masterly execution by which an almost endless variety of objects are blended into one harmonious whole. Three pictures painted for the church of the Jesuits immediately after his return to Mantua, attested how effectually he had prosecuted his studies at Venice. He then developed those powers which afterwards established his reputation, and secured to him a distinction which he still holds without a competitor, that of being the best imitator, and most formidable rival of the Venetian school.

Читать дальше