He never would allow a portrait of himself to be taken. A very well executed bust, which is now in the Library of the Institute, was made from a sketch by a young Italian artist, sent by the Academy of Turin. From this bust our portrait is engraved.

Of the character of Lagrange as a philosopher, no description, in so few words, can be better than that of M. Laplace: “Among the discoverers who have most enlarged the bounds of our knowledge, Newton and Lagrange appear to me to have possessed in the highest degree that happy tact, which leads to the discovery of general principles, and which constitutes true genius for science. This tact, united with a rare degree of elegance in the manner of explaining the most abstract theories, is the characteristic of Lagrange.” This power of generalization distinguishes all that he has written, and the student of the Mécanique Analytique is amazed when he comes to a chapter headed “Equations Différentielles pour la solution de tous les problèmes de Dynamique,” which, on examination, he finds equally applicable, and equally applied, to the vibrations of a pendulum or the motion of a planet. On the exquisite symmetry of his notation and style, we need not enlarge: the mathematician either is acquainted with it, or should become so with all speed; and others will perhaps only smile at the notion of one set of algebraical symbols possessing more elegance or beauty than another.

The separate works of Lagrange are—1. Mécanique Analytique, the second edition of which he was engaged upon when he died; the first edition was published in 1788. 2. Théorie des Fonctions Analytiques, a system of Fluxions on purely algebraical principles; first edition, 1797; second edition, 1813. 3. Leçons sur le Calcul des Fonctions; first published separately in 1806. 4. Résolution des Equations numériques; three editions, in 1798, 1808, and 1826. To give only a list of his separate memoirs would double the length of this life: they will be found in the Miscellanea Taurinensia, tom. i.-v., and 1784–5; Memoirs of the Berlin Academy, 1765–1803; Recueils de l’Académie des Sciences de Paris, 1773–4, and tom. ix.; Mémoires des Savans Etrangers, tom. vii. and x.; Mémoires de l’Institut, 1808–9; Journal de l’École Polytechnique, tom. ii. cahiers 5, 6, tom. viii. cahier 15; Seánces des Écoles Normales; and Connoissance des Tems, 1814, 1817.

7. Éloge de Lagrange, Mémoires de l’Institut. 1812.

8. The admissibility of discontinuous functions into the integrals of partial differential equations.

9. Les principales sociétés savantes de L’Europe, celle de Londres exceptée , s’empressèrent de décorer de son nom la liste de leurs membres.

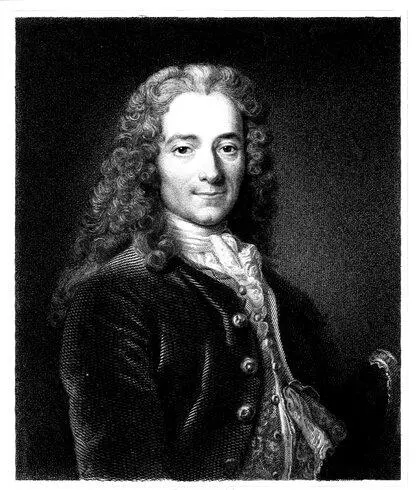

Engraved by Ja s. Mollison. VOLTAIRE. From an original Picture by Largillière in the collection of the Institute of France. Under the Superintendance of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. London, Published by Charles Knight, Pall Mall East.

Table of Contents

François Marie Arouet, who is commonly known by his assumed name, De Voltaire, was born at Châtenay, near Sceaux, February 20, 1694. He soon distinguished himself as a child of extraordinary abilities. The Abbé de Châteauneuf, his godfather, took charge of the elements of his education, and laboured successfully to improve the talents of his ready pupil without much regard to his morals. At three years old the future champion of infidelity had learned by heart the Moisade, an irreligious poem of J. B. Rousseau. These lessons were not forgotten at college, where he passed rapidly through the usual courses of study, and alarmed his Jesuit preceptors by the undisguised licence of his opinions. About this time some of his first attempts at poetry obtained for him the notice of Ninon de l’Enclos; and when the Abbé de Châteauneuf, who had been the last in her long list of favourites, introduced him at her house, she was so pleased with the promising talents of the boy, that she left him by will a legacy of 2,000 francs to purchase books. The Ecole de Droit, where Arouet next studied, was much less suited to his disposition than the College of Louis le Grand. In vain his father urged him to undertake the drudgery of a profession: the Abbé was a more agreeable monitor, and under his auspices the young man sought with eagerness the best Parisian society. At the suppers of the Prince de Conti, he became acquainted with wits and poets, acquired the easy tone of familiar politeness, and distinguished himself by the delicacy of his flatteries, and the liveliness of his repartee. In 1713 he went to Holland as page to the French ambassador, the Marquis de Châteauneuf. This place had been solicited by his father in the hope of detaching him from dissipated habits. But little was gained by the step, for in a short time he was sent back to his family, in consequence of an intrigue with a M lle.Du Noyer, whose mother, a Protestant refugee at the Hague, gained her living by scandal and libels, and on this occasion thought something might be got by complaining to the ambassador, and printing young Arouet’s love-letters. He was, however, not easily discouraged. He endeavoured to interest the Jesuits in his affairs, by representing M lle.Du Noyer as a ready convert, whom it would be Catholic charity to snatch from the influence of an apostate mother. This manœuvre having failed, he sought a reconciliation with his father, who remained a long while implacable; but touched at last by his son’s entreaties to be permitted to see him once more, on condition of leaving the country immediately afterwards for America, he consented to receive him into favour. Arouet again attempted legal studies, but soon abandoned them in disgust. The Regency had now commenced; and among the numerous satires directed against the memory of Louis XIV., one was attributed to him. The report caused him a year’s imprisonment in the Bastille. Soon afterwards he changed the name of Arouet for that of Voltaire. “I have been unhappy,” he said, “so long as I bore the first: let us see if the other will bring better fortune.” It seemed indeed that it did so, for in 1718 the tragedy of Œdipe was represented, and established the reputation of its author. It had been principally composed in the Bastille, where he also laid the foundation of his Henriade, which occupied the time he could spare from amorous and political intrigue, until 1724. Desiring to publish it, he submitted the poem to some select friends, men of severe taste, who met at the house of the President de Maisons. They found so many faults that the author threw the manuscript into the fire. The President Hénault rescued it with difficulty, and said, “Young man, your haste has cost me a pair of best lace ruffles: why should your poem be better than its hero, who was full of faults, yet none of us like him the worse?” Surreptitious copies spread rapidly, and gained for the author much both of celebrity and envy. But it displeased two powerful classes: the priests were apprehensive of its religious, the courtiers of its political, tendency; insomuch that the publication was prohibited by government, and the young king refused to accept the dedication. Soon after this, Voltaire was sent again to the Bastille, in consequence of a quarrel with the Chevalier de Rohan: and on his liberation, he was banished to England. There he remained three years, perhaps the most important era of his life, for it gave an entirely new direction to his lively mind. Hitherto a wit, and a writer of agreeable verse, he became in England a philosopher. Returning to France in 1726, he brought with him an admiration of our manners, and a knowledge of our best writers, which visibly influenced his own compositions and those of his contemporaries. He now published several poetical and dramatic pieces with variable success; but he was more than once forced to quit Paris by the clamour and persecution of his enemies. After the failure of one of his plays, Fontenelle and some other literary associates seriously advised him to abandon the drama, as less suited to his talent than the light style of fugitive poetry in which he had uniformly succeeded. He answered them by writing Zaire, which was acted with great applause in 1732. He had already published his history of Charles XII.: that of Peter the Great was written much later in life. The Lettres Philosophiques, secretly printed at Rouen, and rapidly circulating, increased his popularity, and the zeal of his enemies. This work was burnt by the common hangman. About this time commenced that celebrated intimacy with Emilie Marquise du Châtelet, which for nearly twenty years stimulated and guided his genius. Love made him a mathematician. In the studious leisure of Cirey, under the auspices of “la sublime Emilie,” he plunged himself into the most abstract speculations, and acquired a new title to fame by publishing the Elements of Newton in 1738, and contending for a prize proposed by the Academy of Sciences. At the same time he produced in rapid succession Alzire, Mahomet, and Merope. His fame was now become European. Frederic of Prussia, Stanislaus, and other sovereigns honoured him, or were honoured by his correspondence. But the perpetual intrigues of his enemies at home deprived him of repose, and even at Cirey he was not always free from troubles and altercations. Upon the death of Madame du Châtelet, in 1749, he accepted the often urged invitation of Frederic, and took up his residence at the Court of Berlin. But the friendship of the king and the philosopher was not of long duration. A violent quarrel with the geometrician, Maupertuis, who was also living under the protection of Frederic, ended, after some ineffectual attempts at accommodation, in Voltaire’s departure from Frederic’s society and dominions (1753). He had just published his Siècle de Louis XIV., which was shortly followed by the Essai sur les Mœurs. After a few more wanderings, for the versatility of his talent seemed to require a corresponding variety of abode, Voltaire finally fixed himself at Ferney, near Geneva, in the sixty-fifth year of his eventful life, and began to enjoy at leisure his vast reputation. From all parts of Europe strangers undertook pilgrimages to this philosophic shrine. Sovereigns took pride in corresponding with the Patriarch, as he was called by the numerous sect of free-thinkers, and self-styled philosophers , who looked up to him as their teacher and leader. The Society of Philosophers at Paris, now employed in their great work, the Encyclopædia, which, from the moment of its ill-judged prohibition by the government had assumed the character of an antichristian manifesto, looked up to Voltaire as the acknowledged chief of their party. He furnished some of the most important articles in the work. His whole mind seemed now to be bent on one object, the subversion of the Christian religion. Innumerable miscellaneous compositions, different in form, and generally anonymous, indeed often disavowed, were marked by this pernicious tendency. “I am tired,” he is reported to have said, “of hearing it repeated that twelve men were sufficient to found Christianity: I will show the world that one is sufficient to destroy it!” Half a century has elapsed, and the event has not justified the truth of this boast: he mistook his own strength, as many other unbelievers have done. These impious extravagances were not, however, the only occupation of the twenty years which intervened between Voltaire’s establishment at Ferney and his death. In the defence of Sirven, Lally, Labarre, Calas, and others, who at several times were objects of unjust condemnation by the judicial tribunals, he exerted himself with a zeal as indefatigable as it was meritorious. Ferney, under his protection, grew to a considerable village, and the inhabitants learned to bless the liberalities of their patron. His mind continued to be embittered by literary quarrels, the most memorable being that with J. J. Rousseau, commemorated in his poem, entitled ‘Guerre Civile de Genève’ (1768). He hated this unfortunate exile, as a rival, as an enthusiast, and as a friend, comparatively speaking, to Christianity. Nor were these his only disquietudes. The publication of the infamous poem of La Pucelle, which he suffered in strict confidence to circulate among his intimate friends, and which was printed by the treachery of some of them, gave him much uneasiness. For its indecency and impiety he might not have cared: but all who had offended him, authors, courtiers, even the king and his mistress, were abused in it in the grossest manner, and Voltaire had no wish to provoke the arm of power. He had recourse to his usual process of disavowal, and as he could not deny the whole, he asserted that the offensive parts had been intercalated by his enemies. In other instances his zeal outran discretion, and affected his comforts by producing apprehension for his safety. Sometimes a panic terror of assassination took possession of him, and it needed all the gentleness and assiduities of his adopted daughter, Madame de Varicourt, to whom he was tenderly attached, to bring back his usual levity of mind. At length, in 1778, Voltaire yielding to the entreaties of his favourite niece, Madame Denis, came to Paris, where at the theatre he was greeted by a numerous assemblage in a manner resembling the crowning of an Athenian dramatic poet, more than any modern exhibition of popular favour. Borne back to his hotel amidst the acclamations of thousands, the aged man said feebly, “You are suffocating me with roses.” He did not indeed long survive this festival. Continued study, and the immoderate use of coffee, renewed a strangury to which he had been subject, and he died May 30, 1778. He was interred with the rites of Christian worship, a point concerning which he had shown some solicitude, in the Abbaye de Scellières. In 1791 his remains were removed by the Revolutionists, and deposited with great pomp in the Pantheon.

Читать дальше