There is scarcely any large collection in which the works of Titian are not to be found. The pictures of Actæon and Callisto in the possession of Lord F. L. Gower, and the four subjects in the National Gallery, are among the finest in this country. The Venus in the Dulwich Gallery must have been fine; but the glazing, a very essential part of Titian’s process, has flown.

Details of the life of Titian will be found in Vasari, Lanzi, Ridolfi, but more especially in Ticozzi, whose memoir is at once diffuse and perspicuous. There is a life of Titian, in English, by Northcote.

5. The writer has been informed by Canova that this was his own opinion, and that of Sir Thomas Lawrence.

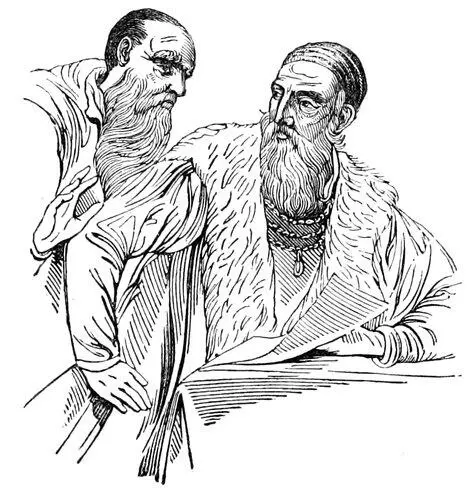

Titian and Francisco di Mosaico, from a picture by Titian.

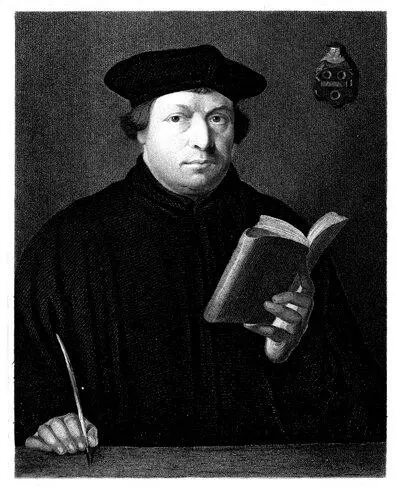

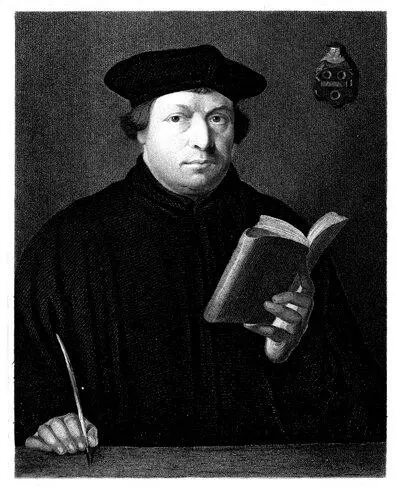

Engraved by C. E. Wagstaff LUTHER. From the original Picture by Holbein in his Majesty’s Collection at Windsor. Under the Superintendance of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. London, Published by Charles Knight, Pall Mall East.

Table of Contents

Martin Luther was born at Eisleben in Saxony in the year 1483, on the 10th of November; and if in the histories of great men it is usual to note with accuracy the day of their nativity, that of Luther has a peculiar claim on the biographer, since it has been the especial object of horoscopical calculations, and has even occasioned some serious differences among very profound astrologers. Luther has been the subject of unqualified admiration and eulogy: he has been assailed by the most virulent calumnies; and, if any thing more were wanted to prove the personal consideration in which he was held by his contemporaries, it would be sufficient to add, that he has also been made a mask for their follies.

He was of humble origin. At an early age he entered with zeal into the Order of Augustinian Hermits, who were Monks and Mendicants. In the schools of the Nominalists he pursued with acuteness and success the science of sophistry. And he was presently raised to the theological chair at Wittemberg: so that his first prejudices were enlisted in the service of the worst portion of the Roman Catholic Church; his opening reason was subjected to the most dangerous perversion; and a sure and early path was opened to his professional ambition. Such was not the discipline which could prepare the mind for any independent exertion; such were not the circumstances from which an ordinary mind could have emerged into the clear atmosphere of truth. In dignity a Professor, in theology an Augustinian, in philosophy a Nominalist, by education a Mendicant Monk, Luther seemed destined to be a pillar of the Roman Catholic Church, and a patron of all its corruptions.

But he possessed a genius naturally vast and penetrating, a memory quick and tenacious, patience inexhaustible, and a fund of learning very considerable for that age: above all, he had an erect and daring spirit, fraught with magnanimity and grandeur, and loving nothing so well as truth; so that his understanding was ever prepared to expand with the occasion, and his principles to change or rise, according to the increase and elevation of his knowledge. Nature had endued him with an ardent soul, a powerful and capacious understanding; education had chilled the one and contracted the other; and when he came forth into the fields of controversy, he had many of those trammels still hanging about him, which patience, and a succession of exertions, and the excitement of dispute, at length enabled him for the most part to cast away.

In the year 1517, John Tetzel, a Dominican Monk, was preaching in Germany the indulgences of Pope Leo X.; that is, he was publicly selling to all purchasers remission of all sins, past, present, or future, however great their number, however enormous their nature. The expressions with which Tetzel recommended his treasure appear to have been marked with peculiar impudence and indecency. But the act had in itself nothing novel or uncommon: the sale of indulgences had long been recognized as the practice of the Roman Catholic Church, and even sometimes censured by its more pious, or more prudent members. But the crisis was at length arrived in which the iniquity could no longer be repeated with impunity. The cup was at length full; and the hand of Luther was destined to dash it to the ground. In the schools of Wittemberg the Professor publicly censured, in ninety-five propositions, not only the extortion of the Indulgence-mongers, but the co-operation of the Pope in seducing the people from the true faith, and calling them away from the only road to salvation.

This first act of Luther’s evangelical life has been hastily ascribed by at least three eminent writers of very different descriptions, (Bossuet, Hume, and Voltaire,) to the narrowest monastic motive, the jealousy of a rival order. It is asserted that the Augustinian Friars had usually been invested in Saxony with the profitable commission, and that it only became offensive to Luther when it was transferred to a Dominican. There is no ground for that assertion. The Dominicans had been for nearly three centuries the peculiar favourites of the Holy See, and objects of all its partialities; and it is particularly remarkable, that, after the middle of the fifteenth century, during a period scandalously fruitful in the abuse in question, we very rarely meet with the name of any Augustinian as employed in that service. Moreover, it is almost equally important to add, that none of the contemporary adversaries of Luther ever advanced the charge against him, even at the moment in which the controversy was carried on with the most unscrupulous rancour.

The matter in dispute between Luther and Tetzel went in the first instance no farther than this—whether the Pope had authority to remit the divine chastisements denounced against offenders in the present and in a future state—or whether his power only extended to such human punishments, as form a part of ecclesiastical discipline—for the latter prerogative was not yet contested by Luther. Nevertheless, his office and his talents drew very general attention to the controversy; the German people, harassed by the exactions, and disgusted with the insolence of the papal emissaries, declared themselves warmly in favour of the Reformer; while on the other hand, the supporters of the abuse were so violent and clamorous, that the sound of the altercation speedily disturbed the festivities of the Vatican.

Leo X., a luxurious, indolent, and secular, though literary pontiff, would have disregarded the broil, and left it, like so many others, to subside of itself, had not the Emperor Maximilian assured him of the dangerous impression it had already made on the German people. Accordingly he commanded Luther to appear at the approaching diet of Augsburg, and justify himself before the papal legate. At the same time he appointed the Cardinal Caietan, a Dominican and a professed enemy of Luther, to be arbiter of the dispute. They met in October, 1518; the legate was imperious; Luther was not submissive. He solicited reasons; he was answered only with authority. He left the city in haste, and appealed “to the Pope better informed ,”—yet it was still to the Pope that he appealed, he still recognized his sovereign supremacy. But in the following month Leo published an edict, in which he claimed the power of delivering sinners from all punishments due to every sort of transgression; and thereupon Luther, despairing of any reasonable accommodation with the pontiff, published an appeal from the Pope to a General Council.

Читать дальше